Sasanian art

It began a new era in Iran and Mesopotamia, which in many ways was built on Achaemenid traditions, including the art of the period.

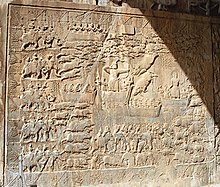

[3] There are important Sassanid rock reliefs, and the Parthian tradition of moulded stucco decoration to buildings continued, also including large figurative scenes.

Images of rulers dominate many of the surviving works, though none are as large as the Colossal Statue of Shapur I.

Hunting and battle scenes enjoyed a special popularity, and lightly clothed dancing girls and entertainers.

[4] It begins with Lullubi and Elamite rock reliefs, such as those at Kul-e Farah and Eshkaft-e Salman in southwest Iran, and continues under the Assyrians.

The Behistun relief and inscription, made around 500 BC for Darius the Great, is on a far grander scale, reflecting and proclaiming the power of the Achaemenid empire.

[5] Persian rulers commonly boasted of their power and achievements, until the Muslim conquest removed imagery from such monuments; much later there was a small revival under the Qajar dynasty.

The problem is helped in the case of the Sassanids by their custom of showing a different style of crown for each king, which can be identified from their coins.

[6] Naqsh-e Rustam is the necropolis of the Achaemenid dynasty (500–330 BC), with four large tombs cut high into the cliff face.

Well below the Achaemenid tombs, near ground level, are rock reliefs with large figures of Sassanian kings, some meeting gods, others in combat.

The placing of these reliefs clearly suggests the Sassanid intention to link themselves with the glories of the earlier Achaemenid Empire.

[9] The seven Sassanian reliefs, whose approximate dates range from 225 to 310 AD, show subjects including investiture scenes and battles.

Another important Sassanid site is Taq Bostan with several reliefs including two royal investitures and a famous figure of a cataphract or Persian heavy cavalryman, about twice life size, probably representing the king Khosrow Parviz mounted on his favourite horse Shabdiz; the pair continued to be celebrated in later Persian literature.

[10] Firuzabad, Fars and Bishapur have groups of Sassanian reliefs, the former including the oldest, a large battle scene, now badly worn.

[6] The standard catalogue of pre-Islamic Persian reliefs lists the known examples (as at 1984) as follows: Lullubi #1–4; Elam #5–19; Assyrian #20–21; Achaemenid #22–30; Late/Post-Achaemenid and Seleucid #31–35; Parthian #36–49; Sasanian #50–84; others #85–88.

A relief at Naqsh-e Rustam is mounted below the Achaemenid royal tombs, and is therefore probably in reference to this, as a way for a monarch to likein and connect himself to the old dynasty and pay homage.

Nothing of this sort remains from the period, although the tradition of the Persian miniature from some centuries later was apparently the earliest in the Islamic world.

One of the few sites where wall-paintings survived in quantity is Panjakent in modern Tajikistan, and ancient Sogdia, which was barely, if at all, under the control of the central Sassanid power.

Large areas of wall paintings survived from the palace and private houses, which are mostly now in the Hermitage Museum or Tashkent.

The subjects are similar to other Sasanian art, with enthroned kings, feasts, battles, and beautiful women, and there are illustrations of both Persian and Indian epics, as well as a complex mixture of deities.

[16] The frescos at Dura Europos, on the frontier of the Roman Empire and Sassanid Persia, are also relevant, with many figures in Persian dress.

At Bishapur floor mosaics in a broadly Greco-Roman style have survived, and these were probably widespread in other elite settings, perhaps made by craftsmen from the Greek world.

The Sassanids further developed the vaults and arches used by the Parthians, usually with a large opening to one side of the hall in iwan style.

These have high-quality engraved or embossed decoration from a courtly repertoire of mounted kings or heroes, and scenes of hunting, combat and feasting, often partially gilded.

[19] A special feature of Sassanid art is represented by shells of silver and gold, on the inner surface of which a scene is etched into a relief.

Another group of metal goods are present; richly decorated vessels whose shape may have been adopted from the customs of the Mediterranean.

Sasanid textiles were famous, and fragments have survived, mostly with designs based on animals in compartments, in a long-lasting style.

The ram was the god of war in connection to Verethragna and therefore held a particular popularity in the Sasanian arts as a motif for textiles.

In simpler forms it seems to have been available to a wide range of the population, and was a popular luxury export to Byzantium and China, even appearing in elite burials from the period in Japan.

A notable example of Sasanian-influenced decorative motifs can be found in the fifth- and sixth-century floor mosaics of Antioch.