Satyricon

As with The Golden Ass by Apuleius (also called the Metamorphoses),[2] classical scholars often describe it as a Roman novel, without necessarily implying continuity with the modern literary form.

[3] The surviving sections of the original (much longer) text detail the bizarre exploits of the narrator, Encolpius, and his (possible) slave and catamite Giton, a handsome sixteen-year-old boy.

In the first passage preserved, Encolpius is in a Greek town in Campania, perhaps Puteoli, where he is standing outside a school, railing against the Asiatic style and false taste in literature, which he blames on the prevailing system of declamatory education (1–2).

An orgy ensues and the sequence ends with Encolpius and Quartilla exchanging kisses while they spy through a keyhole at the mock-wedding between Giton and Pennychis, a seven-year-old virgin girl (26).

This section of the Satyricon, regarded by classicists such as Conte and Rankin as emblematic of Menippean satire, takes place a day or two after the beginning of the extant story.

Encolpius and companions are invited by one of Agamemnon's slaves to a dinner at the estate of Trimalchio, a freedman of enormous wealth, who entertains his guests with ostentatious and grotesque extravagance.

Encolpius listens to their ordinary talk about their neighbors, about the weather, about the hard times, about the public games, and about the education of their children.

In his insightful depiction of everyday Roman life, Petronius delights in exposing the vulgarity and pretentiousness of the illiterate and ostentatious wealthy of his age.

After Trimalchio's return from the lavatory (47), the succession of courses is resumed, some of them disguised as other kinds of food or arranged to resemble certain zodiac signs (35).

Using this sudden alarm as an excuse to get rid of the sophist Agamemnon, whose company Encolpius and his friends are weary of, they flee as if from a real fire (78).

Encolpius returns with his companions to the inn but, having drunk too much wine, passes out while Ascyltos takes advantage of the situation and seduces Giton (79).

After two or three days spent in separate lodgings sulking and brooding on his revenge, Encolpius sets out with sword in hand, but is disarmed by a soldier he encounters in the street (81–82).

The two exchange complaints about their misfortunes (83–84), and Eumolpus tells how, when he pursued an affair with a boy in Pergamon while employed as his tutor, the youth wore him out with his own high libido (85–87).

After talking about the decay of art and the inferiority of the painters and writers of the age to the old masters (88), Eumolpus illustrates a picture of the capture of Troy, Troiae Halosis.

As they travel to the city, Eumolpus lectures on the need for elevated content in poetry (118), which he illustrates with a poem of almost 300 lines on the Civil War between Julius Caesar and Pompey (119–124).

That accomplished, the priestess reveals a "leather dildo" (scorteum fascinum), and the women apply various irritants to him, which they use to prepare Encolpius for anal penetration (138).

However, according to translator and classicist William Arrowsmith, Still, speculation as to the size of the original puts it somewhere on the order of a work of thousands of pages, and comparisons for length range from Tom Jones to In Search of Lost Time.

Servius cites Petronius as his source for a custom at Massilia of allowing a poor man, during times of plague, to volunteer to serve as a scapegoat, receiving support for a year at public expense and then being expelled.

[7] Sidonius Apollinaris refers to "Arbiter", by which he apparently means Petronius's narrator Encolpius, as a worshipper of the "sacred stake" of Priapus in the gardens of Massilia.

Except where the Satyricon imitates colloquial language, as in the speeches of the freedmen at Trimalchio's dinner, its style corresponds with the literary prose of the period.

Eumolpus' poem on the Civil War and the remarks with which he prefaces it (118–124) are generally understood as a response to the Pharsalia of the Neronian poet Lucan.

[20] Petronius mixes together two antithetical genres: the cynic and parodic menippean satire, and the idealizing and sentimental Greek romance.

[20] The name “satyricon” implies that the work belongs to the type to which Varro, imitating the Greek Menippus, had given the character of a medley of prose and verse composition.

The author was happily inspired in his devices for amusing himself and thereby transmitted to modern times a text based on the ordinary experience of contemporary life; the precursor of such novels as Gil Blas by Alain-René Lesage and The Adventures of Roderick Random by Tobias Smollett.

In the realism of Trimalchio's dinner party, we are provided with informal table talk that abounds in vulgarisms and solecisms which give us insight into the unknown Roman proletariat.

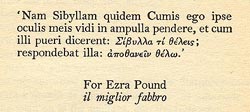

T. S. Eliot's seminal poem of cultural disintegration, The Waste Land, is prefaced by a verbatim quotation out of Trimalchio's account of visiting the Cumaean Sibyl (Chapter 48), a supposedly immortal prophetess whose counsel was once sought on all matters of grave importance, but whose grotto by Neronian times had become just another site of local interest along with all the usual Mediterranean tourist traps: Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumīs ego ipse oculīs meīs vīdī in ampullā pendere, et cum illī puerī dīcerent: "Σίβυλλα τί θέλεις;" respondēbat illa: "ἀποθανεῖν θέλω.

The film is deliberately fragmented and surreal though the androgynous Giton (Max Born) gives the graphic picture of Petronius's character.

Among the chief narrative changes Fellini makes to the Satyricon text is the addition of a hermaphroditic priestess, who does not exist in the Petronian version.

Paul Foster wrote a play (called Satyricon) based on the book, directed by John Vaccaro at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in 1972.

[25] In Foreman's adaptation the presumed author of the book, Petronius, plays an editorializing role, commenting on structural aspects of the text, such as its fragmentary nature, as well as on philosophical themes it addresses, such as 1st-century AD Roman attitudes to slavery.