Scalar potential

A familiar example is potential energy due to gravity.

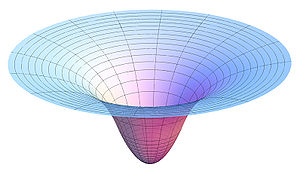

A scalar potential is a fundamental concept in vector analysis and physics (the adjective scalar is frequently omitted if there is no danger of confusion with vector potential).

[a] In some cases, mathematicians may use a positive sign in front of the gradient to define the potential.

[2] Because of this definition of P in terms of the gradient, the direction of F at any point is the direction of the steepest decrease of P at that point, its magnitude is the rate of that decrease per unit length.

In order for F to be described in terms of a scalar potential only, any of the following equivalent statements have to be true: The first of these conditions represents the fundamental theorem of the gradient and is true for any vector field that is a gradient of a differentiable single valued scalar field P. The second condition is a requirement of F so that it can be expressed as the gradient of a scalar function.

A vector field F that satisfies these conditions is said to be irrotational (conservative).

Scalar potentials play a prominent role in many areas of physics and engineering.

The gravity potential is the scalar potential associated with the force of gravity per unit mass, or equivalently, the acceleration due to the field, as a function of position.

Certain aspects of the nuclear force can be described by a Yukawa potential.

The potential play a prominent role in the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian formulations of classical mechanics.

Further, the scalar potential is the fundamental quantity in quantum mechanics.

If F is a conservative vector field (also called irrotational, curl-free, or potential), and its components have continuous partial derivatives, the potential of F with respect to a reference point r0 is defined in terms of the line integral:

The fact that the line integral depends on the path C only through its terminal points r0 and r is, in essence, the path independence property of a conservative vector field.

The fundamental theorem of line integrals implies that if V is defined in this way, then F = –∇V, so that V is a scalar potential of the conservative vector field F. Scalar potential is not determined by the vector field alone: indeed, the gradient of a function is unaffected if a constant is added to it.

If V is defined in terms of the line integral, the ambiguity of V reflects the freedom in the choice of the reference point r0.

An example is the (nearly) uniform gravitational field near the Earth's surface.

This means that gravitational potential energy on a contour map is proportional to altitude.

On a contour map, the two-dimensional negative gradient of the altitude is a two-dimensional vector field, whose vectors are always perpendicular to the contours and also perpendicular to the direction of gravity.

But on the hilly region represented by the contour map, the three-dimensional negative gradient of U always points straight downwards in the direction of gravity; F. However, a ball rolling down a hill cannot move directly downwards due to the normal force of the hill's surface, which cancels out the component of gravity perpendicular to the hill's surface.

The component of gravity that remains to move the ball is parallel to the surface:

where θ is the angle of inclination, and the component of FS perpendicular to gravity is

This force FP, parallel to the ground, is greatest when θ is 45 degrees.

However, on a contour map, the gradient is inversely proportional to Δx, which is not similar to force FP: altitude on a contour map is not exactly a two-dimensional potential field.

The magnitudes of forces are different, but the directions of the forces are the same on a contour map as well as on the hilly region of the Earth's surface represented by the contour map.

Since buoyant force points upwards, in the direction opposite to gravity, then pressure in the fluid increases downwards.

The buoyant force due to a fluid on a solid object immersed and surrounded by that fluid can be obtained by integrating the negative pressure gradient along the surface of the object:

This holds provided E is continuous and vanishes asymptotically to zero towards infinity, decaying faster than 1/r and if the divergence of E likewise vanishes towards infinity, decaying faster than 1/r 2.

This is the fundamental solution of the Laplace equation, meaning that the Laplacian of Γ is equal to the negative of the Dirac delta function:

holds in n-dimensional Euclidean space (n > 2) with the Newtonian potential given then by

Alternatively, integration by parts (or, more rigorously, the properties of convolution) gives