Scanian Law

The different manuscripts are marked by a state of flux in the legal system during and after Valdemar II's reign and sometimes contain conflicting notions of what is considered valid under law.

According to some historians, the ideological battle between royalty and local power structures (the things)[4] taking place in the Nordic countries during this time is evident in the Scanian Law manuscripts.

[5] Jacobsson states that the use of patria in this sense promoted a "royal patriotism with Christian connotations", also supported by Saxo in Gesta Danorum, an ideology that slowly gained acceptance during this era.

[5] This royalty-centered ideology was in conflict with the patriotism expressed by the inhabitants of the different Nordic patriae, who instead stressed loyalty primarily to the area of their thing.

[6] Similar loyalties to the thing area are expressed in Västgötalagen, where people from Sweden and Småland are not considered "natives", and where the law made a difference between "alzmenn" and "ymumenn".

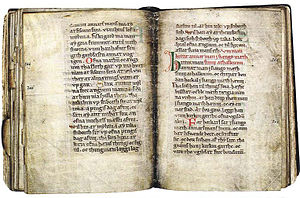

Another well-known manuscript is Anders Sunesøn's 13th-century Latin paraphrase of the Scanian Law (AM 37 4to), created for an international readership.

According to linguist Einar Haugen, the Latin paraphrase was a difficult task for the 13th century scribes: "In his desperate efforts to find Latin equivalents for Danish legal terms, the archbishop is driven to insert expressions in Danish, describing them as being so called in materna lingua vulgariter, or natale ydioma, or vulgari nostro, or most often lingua patria.

[15] Along with Poland, Germany and the Baltic States, Denmark was the country hardest hit by Swedish depredations undertaken to bring literature to Sweden during the 17th century wars, at a time when the country "did not have money to spend on new acquisitions and had limited access to newly published literature", according to the Swedish Royal Library.

Also part of the collection is the oldest known manuscript of the Law Code of Jutland (Jyske Lov), Cod Holm C 37, dated to around 1280.

[20][21] As an alternative to repatriation, the director of the Swedish Royal Library agreed to digitize this and some other manuscripts (including Codex Gigas).

The Danish Royal Library in Copenhagen has set up a website to display the digital facsimile of the Jutland law code and the Internet thus provides a form of "digital repatriation of cultural heritage" according to Ivan Boserup, Keeper of Manuscripts and Rare Books, The Royal Library, Copenhagen.

[22] However, the medieval Scanian manuscripts held at the Royal Library of Sweden are not part of the cultural heritage offered for public view in digitized versions.

[26] Grágás (Grey Goose), the oldest Icelandic law code, is preserved in two vellum manuscripts written shortly after 1250.