Schramm's model of communication

It was first published by Wilbur Schramm in 1954 and includes innovations over previous models, such as the inclusion of a feedback loop and the discussion of the role of fields of experience.

It can be used to mitigate processes that may undermine successful communication, such as external noise or errors in the phases of encoding and decoding.

He discusses the conditions that are needed to have this effect on the audience, such as gaining their attention and motivating them to act towards this goal.

An example is the relation between sender and receiver: it influences the goal of communication and the roles played by the participants.

One shortcoming of Schramm's model is that it assumes that the communicators take turns in exchanging information instead of sending messages simultaneously.

[12][13] The theories of psychologist Charles Osgood were a significant influence and inspired Schramm to formulate his model.

[3] His psycholinguistic approach focuses on how external stimuli elicit internal responses in the form of interpretations.

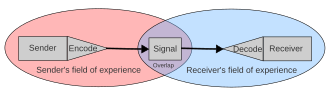

[14] Osgood's ideas influenced Schramm in two important ways: (1) he posited a field of shared experience acting as the background of communication and (2) he added the stages of encoding and decoding as internal responses to the process.

[1][19][20] This can happen in various ways: the signs can be linguistic (like written or spoken words) or non-linguistic (like pictures, music, or animal sounds).

[16] They are then transmitted through a channel, for example, as sounds for a face-to-face conversation, as ink on paper for a letter, or as electronic signals in the case of text messaging.

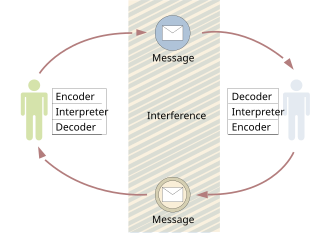

[5][23][24] Because of its emphasis on communication as a circular process, the main focus of Schramm's model is on the behavior of senders and receivers.

For this reason, it does not involve a detailed technical discussion of the channel and influences of noise, unlike the Shannon–Weaver model.

[2][5][20] Communication is an endless process in the sense that people constantly decode and interpret their environment to assign meaning to it and encode possible responses to it.

In such cases, the feedback loop makes it possible to assess whether such errors occurred and, if so, repeat the message to ensure that it is understood correctly.

This happens when the sender pays attention to their own message, for example, when reading through a letter one just wrote to check its style and tone.

[16][30] Blythe cites this lack of overlap as an example of failed communication in the case of foreign advertisements, which may appear incomprehensible or unintentionally humorous.

[16] The lack of overlap can also happen for people within the same culture, for example, when an amateur tries to read specialist scientific literature.

So putting an advertisement in a newspaper, scolding a child, or engaging in a job interview are forms of communication directed at different goals.

To ensure that the message is understandable, the sender must be aware of the field of experience of the audience in order to choose words and examples that are familiar to them.

For example, a political party may use a campaign event to spread fear of an external threat in order to arouse the audience's need for security.

The party may then promise to eliminate this threat to get the audience to act in tune with its intended goal: to secure their votes.

The basic steps like encoding and decoding are the same but they are not performed by a single person but by a group of people, like the employed reporters and editors.

For example, it happens very seldom that a viewer contacts a broadcast network or that a reader writes a letter to an editor.

Feedback is here often more indirect: people may stop to buy a service or to view a program if they are not satisfied with it, usually without providing a reason to the sender for their decision.

It can be based on past face-to-face contact with the other party, as when meeting a friend for dinner, but need not be, as would be the case when reading a newspaper article by a reporter one has never met.

[11][50] It determines many aspects of communication, like its goal, the roles played by the participants, and the expectations they bring to the exchange.

[1][5][20] Schramm's other innovations have also been influential, like his concept of the field of experience and his development of relational models in his later work.

[16][27][57] A common criticism of Schramm's model focuses on the fact that it describes communication as a turn-based exchange of information.

[2] For example, in face-to-face conversations like a first date, the listener usually uses facial expressions and body posture to signal their agreement or interest.

They elaborate Schramm's interactive approach and combine it with the assumption that the communicators create and share meaning with the goal of reaching a mutual understanding.