Science fiction

Precedents for science fiction are argued to exist as far back as antiquity, but the modern genre primarily arose in the 19th and early 20th centuries when popular writers began looking to technological progress and speculation.

"[1] Robert A. Heinlein wrote that "A handy short definition of almost all science fiction might read: realistic speculation about possible future events, based solidly on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the nature and significance of the scientific method.

"[3] Another definition comes from The Literature Book by DK and is, "scenarios that are at the time of writing technologically impossible, extrapolating from present-day science...[,]...or that deal with some form of speculative science-based conceit, such as a society (on Earth or another planet) that has developed in wholly different ways from our own.

[16] Written in the 2nd century CE by the satirist Lucian, A True Story contains many themes and tropes characteristic of modern science fiction, including travel to other worlds, extraterrestrial lifeforms, interplanetary warfare, and artificial life.

[17] Some of the stories from The Arabian Nights,[18][19] along with the 10th-century The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter[19] and Ibn al-Nafis's 13th-century Theologus Autodidactus,[20] are also argued to contain elements of science fiction.

Francis Bacon's New Atlantis (1627),[21] Johannes Kepler's Somnium (1634), Athanasius Kircher's Itinerarium extaticum (1656),[22] Cyrano de Bergerac's Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (1657) and The States and Empires of the Sun (1662), Margaret Cavendish's "The Blazing World" (1666),[23][24][25][26] Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726), Ludvig Holberg's Nicolai Klimii Iter Subterraneum (1741) and Voltaire's Micromégas (1752).

[27] Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan considered Johannes Kepler's Somnium the first science fiction story; it depicts a journey to the Moon and how the Earth's motion is seen from there.

[32][33] Edgar Allan Poe wrote several stories considered to be science fiction, including "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" (1835), which featured a trip to the Moon.

In his non-fiction futurologist works he predicted the advent of airplanes, military tanks, nuclear weapons, satellite television, space travel, and something resembling the World Wide Web.

In its first issue he wrote: By 'scientifiction' I mean the Jules Verne, H. G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe type of story—a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision... Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading—they are always instructive.

[64][65][66] In 1957, Andromeda: A Space-Age Tale by the Russian writer and paleontologist Ivan Yefremov presented a view of a future interstellar communist civilization and is considered one of the most important Soviet science fiction novels.

[77] In the 1960s and 1970s, New Wave science fiction was known for its embrace of a high degree of experimentation, both in form and in content, and a highbrow and self-consciously "literary" or "artistic" sensibility.

[96] In 1984, William Gibson's first novel, Neuromancer, helped popularize cyberpunk and the word "cyberspace", a term he originally coined in his 1982 short story Burning Chrome.

[107] Emerging themes in late 20th and early 21st century science fiction include environmental issues, the implications of the Internet and the expanding information universe, questions about biotechnology, nanotechnology, and post-scarcity societies.

[122][123][124] In 1954, Godzilla, directed by Ishirō Honda, began the kaiju subgenre of science fiction film, which feature large creatures of any form, usually attacking a major city or engaging other monsters in battle.

[125][126] 1968's 2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Stanley Kubrick and based on the work of Arthur C. Clarke, rose above the mostly B-movie offerings up to that time both in scope and quality, and influenced later science fiction films.

the Extra-Terrestrial - 1983), war film (Enemy Mine - 1985), comedy (Spaceballs - 1987, Galaxy Quest - 1999), animation (WALL-E – 2008, Big Hero 6 – 2014), Western (Serenity – 2005), action (Edge of Tomorrow – 2014, The Matrix – 1999), adventure (Jupiter Ascending – 2015, Interstellar – 2014), mystery (Minority Report – 2002), thriller (Ex Machina – 2014), drama (Melancholia – 2011, Predestination – 2014), and romance (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – 2004, Her – 2013).

[139] The first known science fiction television program was a thirty-five-minute adapted excerpt of the play RUR, written by the Czech playwright Karel Čapek, broadcast live from the BBC's Alexandra Palace studios on 11 February 1938.

[144][145] The animated series The Jetsons, while intended as comedy and only running for one season (1962–1963), predicted many inventions now in common use: flat-screen televisions, newspapers on a computer-like screen, computer viruses, video chat, tanning beds, home treadmills, and more.

It is an appeal to the sense of wonder.Carl Sagan said:[187] One of the great benefits of science fiction is that it can convey bits and pieces, hints, and phrases, of knowledge unknown or inaccessible to the reader .

works you ponder over as the water is running out of the bathtub or as you walk through the woods in an early winter snowfall.In 1967, Isaac Asimov commented on the changes then occurring in the science fiction community:[214] And because today's real life so resembles day-before-yesterday's fantasy, the old-time fans are restless.

[219][220] The field has grown considerably since the 1970s with the establishment of more journals, organizations, and conferences, as well as science fiction degree-granting programs such as those offered by the University of Liverpool.

[224] Michael Swanwick dismissed the traditional definition of "hard" SF altogether, instead saying that it was defined by characters striving to solve problems "in the right way–with determination, a touch of stoicism, and the consciousness that the universe is not on his or her side.

"[223] Ursula K. Le Guin also criticized the more traditional view on the difference between "hard" and "soft" SF: "The 'hard' science fiction writers dismiss everything except, well, physics, astronomy, and maybe chemistry.

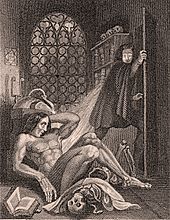

Mary Shelley wrote a number of scientific romance novels in the Gothic literature tradition, including Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818).

[243][244] Jonathan Lethem, in a 1998 essay in the Village Voice entitled "Close Encounters: The Squandered Promise of Science Fiction", suggested that the point in 1973 when Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow was nominated for the Nebula Award and was passed over in favor of Clarke's Rendezvous with Rama, stands as "a hidden tombstone marking the death of the hope that SF was about to merge with the mainstream.

"[245] In the same year science fiction author and physicist Gregory Benford wrote: "SF is perhaps the defining genre of the twentieth century, although its conquering armies are still camped outside the Rome of the literary citadels.

[258] Conventions (in fandom, often shortened as "cons", such as "comic-con") are held in cities around the world, catering to a local, regional, national, or international membership.

[265] The earliest organized online fandom was the SF Lovers Community, originally a mailing list in the late 1970s with a text archive file that was updated regularly.

[267] In the 1990s, the development of the World-Wide Web increased the community of online fandom by of websites devoted to science fiction and related genres for all media.