Psychology of music

[1][2] Modern work in the psychology of music is primarily empirical; its knowledge tends to advance on the basis of interpretations of data collected by systematic observation of and interaction with human participants.

In addition to its basic-science role in the cognitive sciences, the field has practical relevance for many areas, including music performance, composition, education, criticism, and therapy; investigations of human attitude, skill, performance, intelligence, creativity, and social behavior; and links between music and health.

[4] The study of sound and musical phenomena prior to the 19th century was focused primarily on the mathematical modelling of pitch and tone.

[5] The earliest recorded experiments date from the 6th century BCE, most notably in the work of Pythagoras and his establishment of the simple string length ratios that formed the consonances of the octave.

This view that sound and music could be understood from a purely physical standpoint was echoed by such theorists as Anaxagoras and Boethius.

[5] Research by Vincenzo Galilei (father of Galileo) demonstrated that, when string length was held constant, varying its tension, thickness, or composition could alter perceived pitch.

This included further speculation concerning the nature of the sense organs and higher-order processes, particularly by Savart, Helmholtz, and Koenig.

This expanded upon previous centuries of acoustic study, and included Helmholtz developing the resonator to isolate and understand pure and complex tones and their perception, the philosopher Carl Stumpf using church organs and his own musical experience to explore timbre and absolute pitch, and Wundt himself associating the experience of rhythm with kinesthetic tension and relaxation.

Seashore used bespoke equipment and standardized tests to measure how performance deviated from indicated markings and how musical aptitude differed between students.

[5] This period has also seen the founding of journals, societies, conferences, research groups, centers, and degrees that each are specific to the psychology of music.

[7] While the techniques of cognitive psychology allowed for more objective examinations of musical behavior and experience, the theoretical and technological advancements of neuroscience have greatly shaped the direction of the field into the 21st century.

In recent years several bestselling popular science books have helped bring the field into public discussion, notably Daniel Levitin's This Is Your Brain On Music (2006) and The World in Six Songs (2008), Oliver Sacks' Musicophilia (2007), and Gary Marcus' Guitar Zero (2012).

The field draws upon and has significant implications for such areas as philosophy, musicology, and aesthetics, as well the acts of musical composition and performance.

The implications for casual listeners are also great; research has shown that the pleasurable feelings associated with emotional music are the result of dopamine release in the striatum—the same anatomical areas that underpin the anticipatory and rewarding aspects of drug addiction.

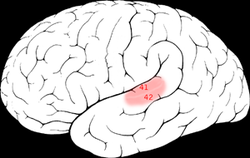

A significant amount of research concerns brain-based mechanisms involved in the cognitive processes underlying music perception and performance.

Scientists working in this field may have training in cognitive neuroscience, neurology, neuroanatomy, psychology, music theory, computer science, and other allied fields, and use such techniques as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), magnetoencephalography (MEG), electroencephalography (EEG), and positron emission tomography (PET).

[26][27] Behavioural studies demonstrate that rhythm and pitch can be perceived separately,[28] but that they also interact[29][30][31] in creating a musical perception.

[35] Even in studies where subjects only listen to rhythms, the basal ganglia, cerebellum, dorsal premotor cortex (dPMC) and supplementary motor area (SMA) are often implicated.

[39] Although auditory–motor interactions can be observed in people without formal musical training, musicians are an excellent population to study because of their long-established and rich associations between auditory and motor systems.

[47] Previous neuroimaging studies have consistently reported activity in the SMA and premotor areas, as well as in auditory cortices, when non-musicians imagine hearing musical excerpts.

More specifically, it is the branch of science studying the psychological and physiological responses associated with sound (including speech and music).

[56][57][58] An alternate view sees music as a by-product of linguistic evolution; a type of "auditory cheesecake" that pleases the senses without providing any adaptive function.

[73] In laboratory settings, music can affect performance on cognitive tasks (memory, attention, and comprehension), both positively and negatively.

The timbre, tempo, lyrics, genre, mood, as well as any positive or negative associations elicited by certain music should fit the nature of the advertisement and product.

[93] Several studies have recognized that listening to music while working affects the productivity of people performing complex cognitive tasks.

One study found that both singing and listening to choral music reduces the level of stress hormones and increases immune function.

Findings showed that a sense of well-being is associated with singing, by uplifting the mood of the participants and releasing endorphins in the brain.

By giving them another medium of communication with their newborns, mothers in one study reported feelings of love and affection when singing to their unborn children.

A song can have nostalgic significance by reminding a singer of the past, and momentarily transport them, allowing them to focus on singing and embrace the activity as an escape from their daily lives and problems.

Singing lowers blood pressure by releasing pent up emotions, boosting relaxation, and reminding them of happy times.