Scotland in the High Middle Ages

However, from 849 on, when Columba's relics were removed from Iona in the face of Viking incursions, written evidence from local sources in the areas under Scandinavian influence all but vanishes for three hundred years.

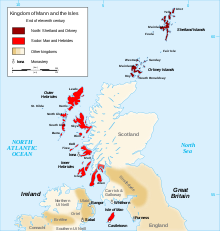

[32] The Scandinavian influence in Scotland was probably at its height in the mid eleventh century[33] during the time of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, who attempted to create a single political and ecclesiastical domain stretching from Shetland to Man.

[45] By the mid-tenth century Amlaíb Cuarán controlled The Rhinns[46] and the region gets the modern name of Galloway from the mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement that produced the Gall-Gaidel.

[50] Although the Scots obtained greater control after the death of Gilla Brigte and the accession of Lochlann in 1185, Galloway was not fully absorbed by Scotland until 1235, after the rebellion of the Galwegians was crushed.

Part of the resource was the large number of children he had, perhaps as many as a dozen, through marriage to the widow or daughter of Thorfinn Sigurdsson and afterwards to the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret, granddaughter of Edmund Ironside.

However, despite having a royal Anglo-Saxon wife, Máel Coluim spent much of his reign conducting slave raids against the English, adding to the woes of that people in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England and the Harrying of the North.

According to the Lanercost Chronicle: the same Mac-William's daughter, who had not long left her mother's womb, innocent as she was, was put to death, in the burgh of Forfar, in view of the market place, after a proclamation by the public crier.

By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a strong position to annex the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did following Haakon Haakonarson's ill-fated invasion and the stalemate of the Battle of Largs with the Treaty of Perth in 1266.

[77][78] The conquest of the west, the creation of the Mormaerdom of Carrick in 1186 and the absorption of the Lordship of Galloway after the Galwegian revolt of Gille Ruadh in 1235[79] meant that Gaelic speakers under the rule of the Scottish king formed a majority of the population during the so-called Norman period.

The integration of Gaelic, Norman and Saxon cultures that began to occur[80] may have been the platform that enabled King Robert I to emerge victorious during the Wars of Independence, which followed soon after the death of Alexander III.

[82] The area that became Scotland in this period is divided by geology into five major regions: the Southern Uplands, Central Lowlands, the Highlands, the North-east coastal plain and the Islands.

The expansion of Alba into the wider Kingdom of Scotland was a gradual process combining external conquest and the suppression of occasional rebellions with the extension of seigniorial power through the placement of effective agents of the crown.

In the ninth century the term mormaer, meaning "great steward", began to appear in the records to describe the rulers of Moray, Strathearn, Buchan, Angus and Mearns, who may have acted as "marcher lords" for the kingdom to counter the Viking threat.

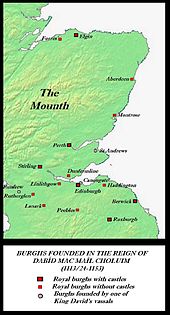

[86] Later the process of consolidation is associated with the feudalism introduced by David I, which, particularly in the east and south where the crown's authority was greatest, saw the placement of lordships, often based on castles, and the creation of administrative sheriffdoms, which overlay the pattern of local thegns.

The legal tract known as Laws of the Brets and Scots, probably compiled in the reign of David I, underlines the importance of the kin group as entitled to compensation for the killing of individual members.

Below them the toísech (leader), appear to have managed areas of the royal demesne, or that of a mormaer or abbot, within which they would have held substantial estates, sometimes described as shires and the title was probably equivalent to the later thane.

[102] There were probably relatively large numbers of free peasant farmers, called husbandmen or bondmen, in the south and north of the country, but fewer in the lands between the Forth and Sutherland until the twelfth century, when landlords began to encourage the formation of such a class through paying better wages and deliberate immigration.

[104] The non-free naviti, neyfs or serfs existed in various forms of service, with terms with their origins in Irish practice, including cumelache, cumherba and scoloc who were tied to a lord's estate and unable to leave it without permission, but who records indicate often absconded for better wages or work in other regions or in the developing burghs.

[103] The introduction of feudalism from the time of David I, not only introduced sheriffdoms that overlay the pattern of local thanes,[102] but also meant that new tenures were held from the king, or a superior lord, in exchange for loyalty and forms of service that were usually military.

In places, feudalism may have tied workers more closely to the land, but the predominantly pastoral nature of Scottish agriculture may have made the imposition of a manorial system on the English model impracticable.

[104] Early Gaelic law tracts, first written down in the ninth century, reveal a society highly concerned with kinship, status, honour and the regulation of blood feuds.

During David I's reign, royal sheriffs had been established in the king's core personal territories; namely, in rough chronological order, at Roxburgh, Scone, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Stirling and Perth.

[119][120] By the twelfth century the ability of lords and the king to call on wider bodies of men beyond their household troops for major campaigns had become the "common" (communis exertcitus) or "Scottish army" (exercitus Scoticanus), the result of a universal obligation based on the holding of variously named units of land.

It would continue to provide the vast majority of Scottish national armies, potentially producing tens of thousands of men for short periods of conflict, into the early modern era.

In the late tenth century the naval battle of "Innisibsolian" (tentatively identified as taking place near the Slate Islands of Argyll)[126][127] was won by Alban forces over Vikings, although this was an unusual setback for the Norse.

[140] The most important missionary saint was Columba, who emerged as a national figure in the combined Scottish and Pictish kingdom,[141] with a new centre established in the east at Dunkeld by Kenneth I for part of his relics.

However, unlike Ireland, which had been granted four Archbishoprics in the same century, Scotland received no Archbishop and the whole Ecclesia Scoticana, with individual Scottish bishoprics (except Whithorn/Galloway), became the "special daughter of the see of Rome".

Scotland's kings maintained an ollamh righe, a royal high poet who had a permanent place in all medieval Gaelic lordships, and whose purpose was to recite genealogies when needed, for occasions such as coronations.

[167] In the thirteenth century, French flourished as a literary language, and produced the Roman de Fergus, one of the earliest pieces of non-Celtic vernacular literature to survive from Scotland.

[169] Playing the harp (clarsach) was especially popular with medieval Scots – half a century after Gerald's writing, King Alexander III kept a royal harpist at his court.