Scotland in the Early Middle Ages

Kingship was multi-layered, with different kings surrounded by their warbands that made up the most important elements of armed forces, and who engaged in both low-level raiding and occasional longer-range, major campaigns.

From the 7th century there is documentary evidence from Latin sources including the lives of saints, such as Adomnán's Life of St. Columba, and Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

[7] At this point the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia was expanding northwards, and the Picts were probably tributary to them until, in 685, Bridei defeated them at the Battle of Dunnichen in Angus, killing their king, Ecgfrith.

Serious defeats in Ireland and Scotland in the time of Domnall Brecc (d. 642) ended Dál Riata's golden age, and the kingdom became a client of Northumbria, then a subject to the Picts.

The first is Coroticus or Ceretic (Ceredig), known as the recipient of a letter from Saint Patrick, and stated by a 7th-century biographer to have been king of the Height of the Clyde, Dumbarton Rock, placing him in the second half of the 5th century.

[14]The Brythonic successor states of what is now the modern Anglo-Scottish border region are referred to by Welsh scholars as part of Yr Hen Ogledd ("The Old North").

Ætherlric's son returned to rule both kingdoms after Æthelfrith had been defeated and killed by the East Anglians in 616, presumably bringing with him the Christianity to which he had converted while in exile.

After his defeat and death at the hands of the Welsh and Mercians at the Battle of Hatfield Chase on 12 October 633, Northumbria again was divided into two kingdoms under pagan kings.

This culminated in the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, which brought to power the House of Alpin, who became the leaders of a combined Gaelic-Pictish kingdom.

[36]Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it has roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles.

This encouraged the spread of blanket peat bog, the acidity of which, combined with high levels of wind and salt spray, made most of the islands treeless.

The existence of hills, mountains, quicksands and marshes made internal communication and conquest extremely difficult and may have contributed to the fragmented nature of political power.

[42] In the areas of Scandinavian settlement in the islands and along the coast a lack of timber meant that native materials had to be adopted for house building, often combining layers of stone with turf.

[5] Early Gaelic settlement appears to have been in the regions of the western mainland of Scotland between Cowal and Ardnamurchan, and the adjacent islands, later extending up the West coast in the 8th century.

Modern linguists divide the Celtic languages into two major groups, the P-Celtic, from which Welsh, Breton and Cornish derive and the Q-Celtic, from which comes Irish, Manx and Gaelic.

Without significant transport links and wider markets, most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by hunter-gathering.

Limited archaeological evidence indicates that throughout Northern Britain farming was based around a single homestead or a small cluster of three or four homes, each probably containing a nuclear family, with relationships likely to be common among neighbouring houses and settlements, reflecting the partition of land through inheritance.

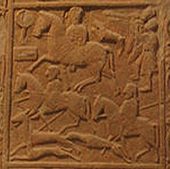

[55] Scattered evidence, including the records in Irish annals and the images of warriors like those depicted on the Pictish stone slabs at Aberlemno, Forfarshire and Hilton of Cadboll in Easter Ross, suggest that in Northern Britain, as in Anglo-Saxon England, society was dominated by a military aristocracy, whose status was dependent in a large part on their ability and willingness to fight.

Interaction with and intermarriage into the ruling families of subject kingdoms may have opened the way to the absorption of such sub-kingdoms and, although there might be later overturnings of these mergers, likely, a complex process by which kingship was gradually monopolised by a handful of the most powerful dynasties was taking place.

[63] The kingship of the unified kingdom of Alba had Scone and its sacred stone at the heart of its coronation ceremony, which historians presume was inherited from Pictish practices.

This shallow draft allowed navigation in waters only 3 feet (1 m) deep and permitted beach landings, while its light weight enabled it to be carried over portages.

The lack of native written sources among the Picts means that it can only be judged from parallels elsewhere, occasional surviving archaeological evidence and hostile accounts of later Christian writers.

The names of more than two hundred Celtic deities have been noted, some of which, like Lugh, The Dagda and The Morrigan, come from later Irish mythology, whilst others, like Teutates, Taranis and Cernunnos, come from evidence from Gaul.

[76] The roots of Christianity in Scotland can probably be found among the soldiers, notably Saint Kessog, son of the king of Cashel, and ordinary Roman citizens in the vicinity of Hadrian's Wall.

[82] St Columba left Ireland and founded the monastery at Iona off the West Coast of Scotland in 563 and from there carried out missions to the Scots of Dál Riata and the Picts.

[90] The part of southern Scotland dominated by the Anglians in this period had a Bishopric established at Abercorn in West Lothian, and it is presumed that it would have adopted the leadership of Rome after the Synod of Whitby in 663, until the Battle of Dunnichen in 685, when the Bishop and his followers were ejected.

[100] Class II stones are carefully shaped slabs dating after the arrival of Christianity in the 8th and 9th centuries, with a cross on one face and a wide range of symbols on the reverse.

[108] For the period after the departure of the Romans, there is evidence of a series of new forts, often smaller "nucleated" constructions compared with those from the Iron Age,[109] sometimes utilising major geographical features, as at Edinburgh and Dunbarton.

[110] All the northern British peoples utilised different forms of fort and the determining factors in construction were local terrain, building materials, and politico-military needs.

These may originally have been wooden, like that excavated at Whithorn,[113] but most of those for which evidence survives from this era are basic masonry-built churches, beginning on the west coast and islands and spreading south and east.