Scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon

[3] The Vichy Secretary of the Navy, Admiral François Darlan, defected to the Allies, who were gaining increasing support from servicemen and civilians.

It may be that General Dwight Eisenhower, with the support of President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, made a secret agreement with Admiral Darlan to give him control of French North Africa if he defected to the Allies.

[23][4] An alternative view is that Darlan was an opportunist and switched sides for self-advancement, thus becoming titular head of French North Africa.

The resolution was that Toulon should remain a "stronghold" under Vichy control and defended against the Allies and "French enemies of the government of the Maréchal".

[25] Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, commander of the Kriegsmarine, believed that Vichy French Navy officers would fulfill their duty under the armistice to not let the ships fall into the hands of a foreign nation.

On the French side, as a token of goodwill towards the Germans, coastal defences were strengthened to safeguard Toulon from an attack from the sea by the Allies.

Crews were initially hostile to the Allied invasion but out of the general anti-German sentiment and as rumours about Darlan's defection circulated, this stance evolved into support for De Gaulle.

"[This quote needs a citation] On 12 November, Admiral Darlan further escalated tensions by calling for the fleet to defect and join the Allies.

[4][24] Vichy military authorities lived in fear of a coup de main organised by the British or by the Free French.

The population of Toulon, defiant of the Germans, mostly supported the Allies; the soldiers and officers were hostile to the Italians who were seen as "illegitimate victors" and duplicitous.

The attack came as a complete surprise to Vichy officers, but Dornon transmitted the order to scuttle the fleet to Admiral Laborde aboard the flagship Strasbourg.

Laborde was taken aback by the German operation, but transmitted orders to prepare for scuttling, and to fire on any unauthorised personnel approaching the ships.

French crews evacuated, and scuttling parties started preparing demolition charges and opening sea valves on the ships.

The German party attempting to board the cruiser Algérie heard the explosions and tried to persuade her crew that scuttling was forbidden under the armistice provisions.

[citation needed] German troops forcibly boarded the cruiser Dupleix, put her crew out of the way, and closed her open sea valves.

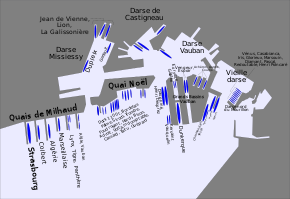

[30] The cruiser Jean de Vienne, in drydock, was boarded by German troops, who disarmed the demolition charges, but the open sea valves flooded the ship.

The crew opened the holes caused by British torpedo attacks to sink the ship, and demolition charges destroyed her vital machinery.

General Charles de Gaulle heavily criticised the Vichy admirals for not ordering the fleet to flee to Algiers.

He had little use for capital ships and other large naval vessels, especially after the sinking of the Bismarck, and so was satisfied considering the elimination of the French fleet to have sealed the success of Case Anton.

[26] The French fleet was annihilated and only a handful of small ships escaped to assist the Allied forces for the rest of the war.

The cruisers Jean de Vienne and La Galissonnière were renamed FR11 and FR12, respectively, but their repair was prevented by Allied bombing and their use would have been unlikely, given the Italians' chronic shortage of fuel.