Scythian genealogical myth

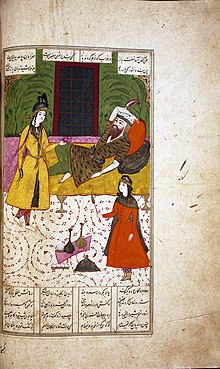

[20] The Snake-Legged Goddess was thus a primordial ancestress of humanity,[21] which made her a liminal figure who founded a dynasty, and was therefore only half-human in appearance while still looking like a snake, itself being a creature capable of passing between the worlds of the living and of the dead with no hindrance.

[24] The legs of the goddess were sometimes instead depicted as tendrils, which also had a similar function by representing fertility, prosperity, renewal, and the afterlife because they grow from the Earth within which the dead were placed and blossom again each year.

[24] The role of the Snake-Legged Goddess in the genealogical myth is not unlike those of sirens and similar non-human beings in Greek mythology, who existed as transgressive women living outside of society and refusing to submit to the yoke of marriage, but instead chose their partners and forced them to join her.

In Hesiod's narrative, "Echidna" was a serpent-nymph living in a cave far from any inhabited lands, and the god Targī̆tavah, assimilated to the Greek hero Hēraklēs, killed two of her children, namely the Hydra of Lerna and the lion of Nemea.

[41] This myth explained the origin of the world,[42] and therefore begun with the Heaven father Pāpaya and the Earth-and-Water Mother Api being already established in their respective places, following the Iranic cosmogenic tradition.

[76] The Scythian genealogical myth was a variant of an old Indo-European tradition present among the Indo-Iranic peoples, especially those who were part of the steppe cultures, according to which the royal dynasty and, by extension, the nation itself, were born from the union of a serpent-nymph and a travelling hero who was searching for his stolen horses.

[69] This conceptualisation of the king originating from the warrior-aristocracy but at the same time encompassing the three social functions and representing all the classes by being himself the incarnation of society was one of the fundamental concepts of Indo-Iranic ideology.

Therefore, the Iranic cosmological features such as the union of heaven and earth and the birth of the primordial unity represented by Targī̆tavah were ignored, and humanity as well as divisions in terms of gender, geography, status, and ethnicity had already come into existence.

The ambiguous features of the mother goddess, such as her being both human and animal, high-ranking and base, monstrous and seductive, at the same time, corresponded to Greek perceptions of Scythian natives.

[121] The Hellenised myth contrasted the chthonic cave-dwelling goddess with the Olympian Hēraklēs, who used the sun-chariot of Helios to complete certain of his labours and to rise to the deities of the celestial realm, and also possessed the bow of Apollo, which had similar attributes.

[123] And unlike the stories where the animals of Hēraklēs were stolen by hostile enemies, the serpent maiden instead opposed the hero's civilising march and in the end obtained an ambiguous victory by permitting him to leave a permanent sign of his passage through the descendance he had with her.

[126][120] The bow of Hēraklēs itself represented prosperity, wisdom, and life, and the trial he instructed the mother to put their sons through was meant to choose the most intelligent, skillful and strong one among them to be the king.

[131] When Herodotus of Halicarnassus recorded the Hellenised version of the genealogical myth, he exhibited scepticism towards this narrative within his own text largely because he doubted that the Ocean encircled the earth, but also partly because he had close connections with the Western Greeks of Magna Graecia, who believed that Hēraklēs had driven the cattle of Gēryōn through their region of the world, and therefore did not accept that he had made a detour to the north to Scythia.

[134] Since Herodotus perceived the Scythians and the Egyptians as being diametrical opposites, the footprint of Hēraklēs in Scythia was also the counterpart to the two cubit-long sandal of Perseus at Khemmis in Egypt: both marked places which had been sacralised by the appearance of heroes and where the divine and human realms overlapped; at the same time, while Hēraklēs had left his permanent footprint in Scythia, Perseus instead had a fleeting presence, so that the presence of his sandal in his sanctuary in Khemmis was a sign of his visit.

[139] At the same time, the Scythians, who were presented as descendants of Hēraklēs in this story, in consequence were protected by him through his divine power to ward off evil, which was also attested through his epithet of alexikakos (αλεξικακος).

[1][157] In Avestan mythology, Haošiiaŋha Paraδāta held the role of the warrior-king who fought against non-Iranic "barbarians" and had both human and demonic enemies, and also laid the foundations of royal power and of sovereignty.

Taxma Urupi in Avestan mythology also curbed idolatry and promoted the worship of Ahura Mazdā, and was also credited with inventing writing, which were all attributes of a priest-king, thus making him the equivalent of Lipoxšaya.

[161] Yima's epithet of xšaēta (𐬑𐬱𐬀𐬉𐬙𐬀), meaning "brilliant" and "shining" was a sign of his proximity to the Sun and the Moon due to his possession of the xᵛarᵊnah in his capacity of being king.

Ahura Mazdā then offered kingship of the whole world to Yima, and he accepted and therefore received the suβrā and aštrā, which are described in the text of the Vendīdād as the xšaθra, meaning "royal powers," and which respectively represent the farmer and warrior functions.

[170] These differences resulted from innovations by the priestly class to discredit the claims of the kings of being the divine agents, and which were canonised in the myth of Yima believing the lies.

[175] The theme of the primordial unity of creation was also present in the Zoroastrian cosmogenetic myth, where Ahura Mazdā created the Sky, Water, Earth, Plant, Animal, and Human.

However, the death of these primordial beings was not their end, and they instead fragmented into smaller parts which then became the many types of plants, animals, and humans, all of which contained both some good and some evil, and the ability to reproduce, which was itself the replacement of immortality by the perpetuation of the species.

Thus, the original perfection was replaced by a combination of good and evil, and the shattered primordial unity became a multiplicity, with these changes creating the possibility for the arising of confusion and conflict.

Therefore, Zoroastrianism considers unity and harmony as achievable by performing sacrifice, purification, and recitation of sacred hymns, due to which it places priests as the ones in charge of restoring the primordial perfection.

[173] The theme of the promordial unity was also present among the religion of the ancient Persians, and was often mentioned in Achaemenid royal inscriptions,[180] in which the kings held Ahura Mazda as the source of all creation who brought Heaven, Earth, humanity, and happiness into existence.

[179] The myth of an ancient and pious king whose three sons were the progenitors of the three social classes appears to have existed among the Persians up till the Sasanian period in the 5th century AD.

The Persian practice of proskynēsis, whereby all who met the Achaemenid king had to prostrate before him and had to wait for his permission to rise up again, might have developed as a way to prevent ordinary humans from losing their eyesight or lives by accidentally seeing the royal farnah.

[204] According to Megasthenes's narrative, when "Dionysos" first arrived in India, he found that there was no agriculture, with the people living in a state of savagery, the land remaining uncultivated and not bearing any fruits.

These objects held the same function in the Scythian genealogical myth[74] The axe of Kolaxšaya meanwhile semantically corresponded to the percussive instruments wielded by Indra, who was also the god of thunder and rain, such as his ghanaḥ (mace) and vajra (thunderbolt).

Similarly to the Scythian Snake-Legged Goddess, Cecrops was an autochton born from the Earth, and he was human above the waist and a snake below it, which indicated his dual character as being associated with the nether world and death as well as with life and renewal.