Helios

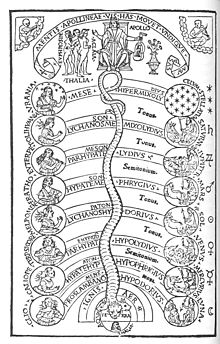

Though Helios was a relatively minor deity in Classical Greece, his worship grew more prominent in late antiquity thanks to his identification with several major solar divinities of the Roman period, particularly Apollo and Sol.

Helios figures prominently in several works of Greek mythology, poetry, and literature, in which he is often described as the son of the Titans Hyperion and Theia and brother of the goddesses Selene (the Moon) and Eos (the Dawn).

The Greek noun ἥλιος (GEN ἡλίου, DAT ἡλίῳ, ACC ἥλιον, VOC ἥλιε) (from earlier ἁϝέλιος /hāwelios/) is the inherited word for the Sun from Proto-Indo-European *seh₂u-el[4] which is cognate with Latin sol, Sanskrit surya, Old English swegl, Old Norse sól, Welsh haul, Avestan hvar, etc.

Doric Greek retained Proto-Greek long *ā as α, while Attic changed it in most cases, including in this word, to η. Cratylus and the etymologies Plato gives are contradicted by modern scholarship.

[41] Helios is said to drive a golden chariot drawn by four horses:[42][43] Pyrois ("The Fiery One", not to be confused with Pyroeis, one of the five naked-eye planets known to ancient Greek and Roman astronomers), Aeos ("He of the Dawn"), Aethon ("Blazing"), and Phlegon ("Burning").

[52] Aeschylus describes the sunset as such: "There [is] the sacred wave, and the coralled bed of the Erythræan Sea, and [there] the luxuriant marsh of the Ethiopians, situated near the ocean, glitters like polished brass; where daily in the soft and tepid stream, the all-seeing Sun bathes his undying self, and refreshes his weary steeds.

In the name of Zeus, swift driver of horses, I beg you, turn the universal omen, lady, into some painless prosperity for Thebes ... Do you bring a sign of some war or wasting of crops or a mass of snow beyond telling or ruinous strife or emptying of the sea on land or frost on the earth or a rainy summer flowing with raging water, or will you flood the land and create a new race of men from the beginning?Some lists, cited by Hyginus, of the names of horses that pulled Helios' chariot, are as follows.

[97] In a surviving fragment from the play, Helios accompanies his son in his ill-fated journey in the skies, trying to give him instructions on how to drive the chariot while he rides on a spare horse named Sirius,[98] as someone, perhaps a paedagogus informs Clymene of Phaethon's fate, who is probably accompanied by slave women: Take, for instance, that passage in which Helios, in handing the reins to his son, says— "Drive on, but shun the burning Libyan tract; The hot dry air will let thine axle down: Toward the seven Pleiades keep thy steadfast way."

[103] Nonnus of Panopolis presented a slightly different version of the myth, narrated by Hermes; according to him, Helios met and fell in love with Clymene, the daughter of the Ocean, and the two soon got married with her father's blessing.

[108] But, Goddess, give up for good your great lamentation.You must not nurse in vain insatiable anger.Among the gods Aidoneus is not an unsuitable bridegroom,Commander-of-Many and Zeus's own brother of the same stock.As for honor, he got his third at the world's first divisionand dwells with those whose rule has fallen to his lot.Helios is said to have seen and stood witness to everything that happened where his light shone.

In Book Eight of the Odyssey, the blind singer Demodocus describes how the illicit lovers committed adultery, until one day Helios caught them in the act, and immediately informed Aphrodite's husband Hephaestus.

Clytie, spurned by Helios for her role in his lover's death, strips herself naked, accepting no food or drink, and sits on a rock for nine days, pining after him, until eventually turning into a purple, sun-gazing flower, the heliotrope.

[119] Leucothoe being buried alive as punishment by a male guardian, which is not too unlike Antigone's own fate, may also indicate an ancient tradition involving human sacrifice in a vegetation cult.

[172] Diodorus Siculus recorded an unorthodox version of the myth, in which Basileia, who had succeeded her father Uranus to his royal throne, married her brother Hyperion, and had two children, a son Helios and a daughter Selene.

After the massacre, Helios appeared in a dream to his grieving mother and assured her and their murderers would be punished, and that he and his sister would now be transformed into immortal, divine natures; what was known as Mene[173] would now be called Selene, and the "holy fire" in the heavens would bear his own name.

[184] Ioannes Tzetzes adds Calypso, otherwise the daughter of Atlas, to the list of children Helios had by Perse, perhaps due to the similarities of the roles and personalities she and Circe display in the Odyssey as hosts of Odysseus.

[194][195] In Seneca's rendition of the story, a frustrated Medea criticizes the inaction of her grandfather, wondering why he has not darkened the sky at sight of such wickedness, and asks from him his fiery chariot so she can burn Corinth to the ground.

[300] The best of these are, first, the Colossus of Helius, of which the author of the iambic verse says, "seven times ten cubits in height, the work of Chares the Lindian"; but it now lies on the ground, having been thrown down by an earthquake and broken at the knees.

[329] Archaeological evidence has proven the existence of a shrine to Helios and Hemera, the goddess of the day and daylight, at the island of Kos[309] and excavations have revealed traces of his cult at Sinope, Pozzuoli, Ostia and elsewhere.

[331] Plato in his Laws mentions the state of the Magnetes making a joint offering to Helios and Apollo, indicating a close relationship between the cults of those two gods,[332] but it is clear that they were nevertheless distinct deities in Thessaly.

[336] In Apollonia he was also venerated, as evidenced from Herodotus' account where a man named Evenius was harshly punished by his fellow citizens for allowing wolves to devour the flock of sheep sacred to the god out of negligence.

[345] The combination of Zeus, Gaia and Helios in oath-swearing is also found among the non-Greek 'Royal Gods' in an agreement between Maussollus and Phaselis (360s BC) and in the Hellenistic period with the degree of Chremonides' announcing the alliance of Athens and Sparta.

[13] The Neoplatonist philosophers Proclus and Iamblichus attempted to interpret many of the syntheses found in the Greek Magical Papyri and other writings that regarded Helios as all-encompassing, with the attributes of many other divine entities.

[382][383] Strabo wrote that Artemis and Apollo were associated with Selene and Helios respectively due to the changes those two celestial bodies caused in the temperature of the air, as the twins were gods of pestilential diseases and sudden deaths.

[389] Scythinus of Teos wrote that Apollo uses the bright light of the Sun (λαμπρὸν πλῆκτρον ἡλίου φάος) as his harp-quill[390] and in a fragment of Timotheus' lyric, Helios is invoked as an archer with the invocation Ἰὲ Παιάν (a common way of addressing the two medicine gods), though it most likely was part of esoteric doctrine, rather than a popular and widespread belief.

A dedicatory inscription from Smyrna describes a 1st–2nd century sanctuary to "God Himself" as the most exalted of a group of six deities, including clothed statues of Plouton Helios and Koure Selene, or in other words "Pluto the Sun" and "Kore the Moon".

[13] The earliest depictions of Helios in a humanoid form date from the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC in Attic black-figure vases, and typically show him frontally as a bearded man on his chariot with a sun disk.

[438] Other rulers who had their portraits done with solar features include Ptolemy III Euergetes, one of the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt, of whom a bust with holes in the fillet for the sunrays and gold coins depicting him with a radiant halo on his head like Helios and holding the aegis exist.

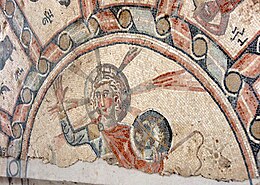

In the mosaic of the Hammat Tiberias, Helios is wrapped in a partially gilded tunic fastened with a fibula and sporting a seven-rayed halo[441] with his right hand uplifted, while his left holds a globe and a whip; his chariot is drawn as a frontal box with two large wheels pulled by four horses.

[444] At the Beth Alpha synagogue, Helios is at the centre of the circle of the zodiac mosaic, together with the Torah shrine between menorahs, other ritual objects, and a pair of lions, while the Seasons are in spandrels.