Sea otter

Adult sea otters typically weigh between 14 and 45 kg (30 and 100 lb), making them the heaviest members of the weasel family, but among[3] the smallest marine mammals.

Unlike most marine mammals, the sea otter's primary form of insulation is an exceptionally thick coat of fur, the densest in the animal kingdom.

Sea otters, whose numbers were once estimated at 150,000–300,000, were hunted extensively for their fur between 1741 and 1911, and the world population fell to 1,000–2,000 individuals living in a fraction of their historic range.

[5] A subsequent international ban on hunting, sea otter conservation efforts, and reintroduction programs into previously populated areas have contributed to numbers rebounding, and the species occupies about two-thirds of its former range.

The recovery of the sea otter is considered an important success in marine conservation, although populations in the Aleutian Islands and California have recently declined or have plateaued at depressed levels.

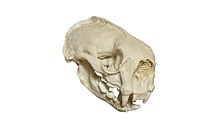

[8] The only living member of the genus Enhydra, the sea otter is so different from other mustelid species that, as recently as 1982, some scientists believed it was more closely related to the earless seals.

[12] The modern sea otter evolved initially in northern Hokkaidō and Russia, and then spread east to the Aleutian Islands, mainland Alaska, and down the North American coast.

[13] In comparison to cetaceans, sirenians, and pinnipeds, which entered the water approximately 50, 40, and 20 million years ago, respectively, the sea otter is a relative newcomer to a marine existence.

[17] This led to genetic drift, as the populations of northern and southern sea otters were cut off from one another by thousands of miles, leading to significant genomic differences.

[44] Blubber can also additionally serve as an energy source for deep dives,[45] which would most likely prove advantageous over fur in the evolutionary future of sea otters.

The sea otter propels itself underwater by moving the rear end of its body, including its tail and hind feet, up and down,[38] and is capable of speeds of up to 9 kilometres per hour (5.6 mph).

[48] The sea otter's body is highly buoyant because of its large lung capacity – about 2.5 times greater than that of similar-sized land mammals[49] – and the air trapped in its fur.

It must eat an estimated 25 to 38% of its own body weight in food each day to burn the calories necessary to counteract the loss of heat due to the cold water environment.

[102] The sea otter population is thought to have once been 150,000 to 300,000,[24] stretching in an arc across the North Pacific from northern Japan to the central Baja California Peninsula in Mexico.

Sea otters currently have stable populations in parts of the Russian east coast, Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, and California, with reports of recolonizations in Mexico and Japan.

This population increased to over 5,600 in 2013 with an estimated annual growth rate of 7.2%, and their range on the island's west coast extended north to Cape Scott and across the Queen Charlotte Strait to the Broughton Archipelago and south to Clayoquot Sound and Tofino.

[124] By 1817, sea otters in the area were practically eliminated and the Russians sought permission from the Spanish and the Mexican governments to hunt further and further south of San Francisco.

In addition, white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni), a species never overlapping with sea otter, had declined in numbers 99% by 1996, and became the first marine invertebrate to be federally listed as endangered.

Cyanobacteria are found in stagnant water enriched with nitrogen and phosphorus from septic tank and agricultural fertilizer runoff, and may be flushed into the ocean when streamflows are high in the rainy season.

There was some contraction from the northern (now Pigeon Point) and southern limits of the sea otter's range during the end of this period, circumstantially related to an increase in lethal shark bites, raising concerns that the population had reached a plateau.

Under Aleksander I, the administration of the merchant-controlled company was transferred to the Imperial Navy, largely due to the alarming reports by naval officers of native abuse; in 1818, the indigenous peoples of Alaska were granted civil rights equivalent to a townsman status in the Russian Empire.

[81] In 1911, Russia, Japan, Great Britain (for Canada) and the United States signed the Treaty for the Preservation and Protection of Fur Seals, imposing a moratorium on the harvesting of sea otters.

[21] The small geographic ranges of the sea otter populations in California, Washington, and British Columbia mean a single major spill could be catastrophic for that state or province.

[198] The debate is complicated because sea otters have sometimes been held responsible for declines of shellfish stocks that were more likely caused by overfishing, disease, pollution, and seismic activity.

These cultures, many of which have strongly animist traditions full of legends and stories in which many aspects of the natural world are associated with spirits, regarded the sea otter as particularly kin to humans.

[207] These stories have been associated with the many human-like behavioral features of the sea otter, including apparent playfulness, strong mother-pup bonds and tool use, yielding to ready anthropomorphism.

The Ainu and Aleuts have been displaced or their numbers are dwindling, while the coastal tribes of North America, where the otter is in any case greatly depleted, no longer rely as intimately on sea mammals for survival.

[191] The round, expressive face and soft, furry body of the sea otter are depicted in a wide variety of souvenirs, postcards, clothing, and stuffed toys.

[218][219][220] Beginning in 2019, the streamer Douglas Wreden, popularly known as DougDoug, has held charity streams for the Monterey Bay Aquarium to celebrate the birthday of Rosa the sea otter.

It is organized and sponsored by Defenders of Wildlife, the Monterey Bay Aquarium, the California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sea Otter Savvy, and the Elakha Alliance.