Sea urchin

Like other echinoderms, they have five-fold symmetry (called pentamerism) and move by means of hundreds of tiny, transparent, adhesive "tube feet".

[4] They have a rigid, usually spherical body bearing moveable spines, which give the class the name Echinoidea (from the Greek ἐχῖνος ekhinos 'spine').

This is most apparent in the "regular" sea urchins, which have roughly spherical bodies with five equally sized parts radiating out from their central axes.

[a][2] Several sea urchins, however, including the sand dollars, are oval in shape, with distinct front and rear ends, giving them a degree of bilateral symmetry.

[4] The internal organs are enclosed in a hard shell or test composed of fused plates of calcium carbonate covered by a thin dermis and epidermis.

This is because it is covered with a thin layer of muscle and skin; sea urchins also do not need to molt the way invertebrates with true exoskeletons do, instead the plates forming the test grow as the animal does.

[12] Most species have two series of spines, primary (long) and secondary (short), distributed over the surface of the body, with the shortest at the poles and the longest at the equator.

An inverted sea urchin can right itself by progressively attaching and detaching its tube feet and manipulating its spines to roll its body upright.

[4] The jaw apparatus consists of five strong arrow-shaped plates known as pyramids, the ventral surface of each of which has a toothband with a hard tooth pointing towards the centre of the mouth.

This coelomic fluid contains phagocytic coelomocytes, which move through the vascular and hemal systems and are involved in internal transport and gas exchange.

The coelomocytes are an essential part of blood clotting, but also collect waste products and actively remove them from the body through the gills and tube feet.

Fluid can be pumped through the gills' interiors by muscles associated with the lantern, but this does not provide a continuous flow, and occurs only when the animal is low in oxygen.

Tube feet can also act as respiratory organs, and are the primary sites of gas exchange in heart urchins and sand dollars, both of which lack gills.

Each gonad has a single duct rising from the upper pole to open at a gonopore lying in one of the genital plates surrounding the anus.

[2] The gonads are lined with muscles underneath the peritoneum, and these allow the animal to squeeze its gametes through the duct and into the surrounding sea water, where fertilization takes place.

[4] During early development, the sea urchin embryo undergoes 10 cycles of cell division,[21] resulting in a single epithelial layer enveloping the blastocoel.

The embryo then begins gastrulation, a multipart process which dramatically rearranges its structure by invagination to produce the three germ layers, involving an epithelial-mesenchymal transition; primary mesenchyme cells move into the blastocoel[22] and become mesoderm.

[30] Another condition, bald sea urchin disease, causes loss of spines and skin lesions and is believed to be bacterial in origin.

All these animals carry particular adaptations (teeth, pincers, claws) and a strength that allow them to overcome the excellent protective features of sea urchins.

One of the deepest-living families is the Pourtalesiidae,[41] strange bottle-shaped irregular sea urchins that live in only the hadal zone and have been collected as deep as 6850 metres beneath the surface in the Sunda Trench.

[40] The larvae of the polar sea urchin Sterechinus neumayeri have been found to use energy in metabolic processes twenty-five times more efficiently than do most other organisms.

[46] Despite their presence in nearly all the marine ecosystems, most species are found on temperate and tropical coasts, between the surface and some tens of meters deep, close to photosynthetic food sources.

[51] Most fossil echinoids from the Paleozoic era are incomplete, consisting of isolated spines and small clusters of scattered plates from crushed individuals, mostly in Devonian and Carboniferous rocks.

Their distinctive, flattened tests and tiny spines were adapted to life on or under loose sand in shallow water, and they are abundant as fossils in southern European limestones and sandstones.

[64] More recently, Eric H. Davidson and Roy John Britten argued for the use of urchins as a model organism due to their easy availability, high fecundity, and long lifespan.

The sequencing also revealed that while some genes were thought to be limited to vertebrates, there were also innovations that have previously never been seen outside the chordate classification, such as immune transcription factors PU.1 and SPIB.

[70][71][72] In Japan, sea urchin is known as uni (うに), and its gonads (the only meaty, edible parts of the animal) can retail for as much as ¥40,000 ($360) per kilogram;[73] they are served raw as sashimi or in sushi, with soy sauce and wasabi.

[78] In Mediterranean cuisines, Paracentrotus lividus is often eaten raw, or with lemon,[79] and known as ricci on Italian menus where it is sometimes used in pasta sauces.

[89] A folk tradition in Denmark and southern England imagined sea urchin fossils to be thunderbolts, able to ward off harm by lightning or by witchcraft, as an apotropaic symbol.

[90] Another version supposed they were petrified eggs of snakes, able to protect against heart and liver disease, poisons, and injury in battle, and accordingly they were carried as amulets.

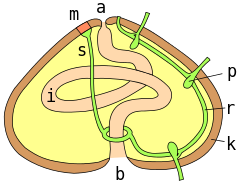

a = anus ; m = madreporite ; s = aquifer canal; r = radial canal; p = podial ampulla; k = test wall; i = intestine ; b = mouth