Seal (emblem)

However engraved gems were often carved in relief, called cameo in this context, giving a "counter-relief" or intaglio impression when used as seals.

Most seals have always given a single impression on an essentially flat surface, but in medieval Europe two-sided seals with two matrices were often used by institutions or rulers (such as towns, bishops and kings) to make two-sided or fully three-dimensional impressions in wax, with a "tag", a piece of ribbon or strip of parchment, running through them.

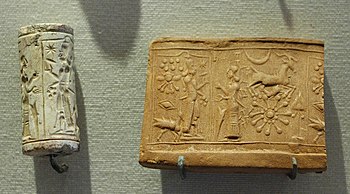

These could be rolled along to create an impression on clay (which could be repeated indefinitely), and used as labels on consignments of trade goods, or for other purposes.

One example shows a name written in Aramaic (Yitsḥaq bar Ḥanina) engraved in reverse so as to read correctly in the impression.

From the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC until the Middle Ages, seals of various kinds were in production in the Aegean islands and mainland Greece.

[7] Even in modern times, seals, often known as "chops" in local colloquial English, are still commonly used instead of handwritten signatures to authenticate official documents or financial transactions.

East Asian seals are carved from a variety of hard materials, including wood, soapstone, sea glass and jade.

[8] During the early Middle Ages seals of lead, or more properly "bullae" (from the Latin), were in common use both in East and West, but with the notable exception of documents ("bulls") issued by the Papal Chancery these leaden authentications fell out of favour in western Christendom.

In England, few wax seals have survived of earlier date than the Norman Conquest,[9] although some earlier matrices are known, recovered from archaeological contexts: the earliest is a gold double-sided matrix found near Postwick, Norfolk, and dated to the late 7th century; the next oldest is a mid-9th-century matrix of a Bishop Ethilwald (probably Æthelwold, Bishop of East Anglia).

[12] They also came to be used by a variety of corporate bodies, including cathedral chapters, municipalities, monasteries etc., to validate the acts executed in their name.

In Central and Eastern Europe, however, as in East Asia, a signature alone is considered insufficient to authenticate a document of any kind in business, and all managers, as well as many book-keepers and other employees, have personal seals[citation needed], normally just containing text, with their name and their position.

A pendent seal may be attached to cords or ribbons (sometimes in the owner's livery colors), or to the two ends of a strip (or tag) of parchment, threaded through holes or slots cut in the lower edge of the document: the document is often folded double at this point (a plica) to provide extra strength.

Alternatively, the seal may be attached to a narrow strip of the material of the document (again, in this case, usually parchment), sliced and folded down, as a tail or tongue, but not detached.

The design generally comprised a graphic emblem (sometimes, but not always, incorporating heraldic devices), surrounded by a text (the legend) running around the perimeter.

[18] Sealing wax was naturally yellowish or pale brownish in tone, but could also be artificially colored red or green (with many intermediary variations).

In some medieval royal chanceries, different colours of wax were customarily used for different functions or departments of state, or to distinguish grants and decrees made in perpetuity from more ephemeral documents.

Sometimes, a large official seal, which might be in the custody of chancery officials, would need to be counter-sealed by the individual in whose name it had been applied (the monarch, or the mayor of a town): such a counter-seal might be carried on the person (perhaps secured by a chain or cord), or later, take the form of a signet ring, and so would be necessarily smaller.

[22][23] Certain medieval seals were more complex still, involving two levels of impression on each side of the wax which would be used to create a scene of three-dimensional depth.

[24][25] On the death of a seal-holder, as a sign of continuity, a son and heir might commission a new seal employing the same symbols and design-elements as those used by his father.

The use of a seal by men of wealth and position was common before the Christian era, but high functionaries of the Church adopted the habit.

[28][9] Later ecclesiastical synods require that letters under the bishop's seal should be given to priests when for some reason they lawfully quit their own proper diocese.

Pope Nicholas I in the same century complained that the bishops of Dôle and Reims had, "contra morem" (contrary to custom), sent their letters to him unsealed.

[9] Seals are also affixed on architectural or engineering construction documents, or land survey drawings, to certify the identity of the licensed professional who supervised the development.

[30][31][32] Depending on the authority having jurisdiction for the project, these seals may be embossed and signed, stamped and signed, or in certain situations a computer generated facsimile of the original seal validated by a digital certificate owned by the professional may be attached to a security protected computer file.

In old English law, a cocket was a custom house seal; or a certified document given to a shipper as a warrant that his goods have been duly entered and have paid duty.

When the pope dies it is the first duty of the Cardinal Camerlengo to obtain possession of the Ring of the Fisherman, the papal signet, and to see that it is broken up.

"[37] Matthew Paris gives a similar description of the breaking of the seal of William of Trumpington, Abbot of St Albans, in 1235.

[40][41] When King James II of England was dethroned in the Glorious Revolution of 1688/9, he is supposed to have thrown the Great Seal of the Realm into the River Thames before his flight to France in order to ensure that the machinery of government would cease to function.

The wearing of signet rings (from Latin "signum" meaning "sign" or "mark") dates back to ancient Egypt: the seal of a pharaoh is mentioned in the Book of Genesis.

[47][48] Specially-made tamper-evident labels are available which are destroyed if the protected container or equipment is opened, functionally equivalent to a wax seal.