Seara (newspaper)

[3] Early in its existence, Seara reported on various events agitating public opinion, such as the Romanian Orthodox Church division between the traditionalists and those who supported communion with Rome.

Shortly before the Balkan Wars, it published the appeal of Simion, a Greek Romanian politician and editor of Bucharest's Patris gazette, who gathered support for a Greco–Romanian alliance against the South Slavs.

Simion posited that Romania and the Kingdom of Greece would eventually reach an understanding over the litigious issue of Aromanian nationhood, and blamed the conflict on "shrewd" Slavic meddling.

During late 1910, Karnabatt gave poor reviews to the more rebellious Symbolist painters to emerge from the Tinerimea Artistică salon, and deemed the primitivist sculptor Constantin Brâncuși a madman.

[21] He was revolted by "the horrors of contemporary painting"—Pissarro, Monet, etc.—, citing as his reference "the fine and erudite art critic, the independent and courageous" Sâr Péladan (who was, incidentally, Bogdan-Pitești's mentor).

[22] In a September issue, "Don Ramiro" Karnabatt declared himself horrified that some were proposing to honor the inveterate gambler Avrillon with a public monument, announcing that France had given in to "vice".

[23] By then, he was giving positive reviews to "decadent poets" of the "dead cities" (Georges Rodenbach, Dimitrie Anghel), and enthusiastic about the establishment of community theaters to promote a "noble and pure art", away from "the platitudes and pettiness of modern life".

[27] Bogdan-Pitești, whose background was in French anarchism,[28] announced that the new editorial line centered on some of Cantacuzino's bugbears: universal suffrage, feminism, land reform, Jewish emancipation etc.

"[31] In a 1913 issue, Romanian Land Forces General Ștefan Stoica referred to Ionescu's men as craii de Curtea-Veche ("the Old Court rakes"), another colloquialism for "upstarts".

[30][31] One of Seara's prime targets was Public Works Minister Alexandru Bădărău, called "filthy con man", accused of taking massive bribes from American investors in Romanian oil and of employing in his staff some 150 women in exchange for sexual favors.

[31][33] In diaries he kept after his split with Bogdan-Pitești, Caragiale himself alleged that Seara's publisher was being paid to harass "without pity, in biting manner, all those whom Cantacuzino would grace with his unfriendliness or antipathy", in particular the Conservative-Democrats.

[35] According to the records kept by Caragiale, Blank effectively set a "trap" with the cooperation of Romanian Police, and Bogdan-Pitești, found guilty of blackmail, was sentenced to nine months in prison.

[31][36] Before and after the 1913 hiatus, with Bogdan-Pitești and Arghezi at its helm, Seara expanded its range, encouraging the development of modernist literature, and playing a part in the transition from Romanian Symbolism to 20th century avant-garde.

[51] In October 1913, Seara obtained and published a confidential order which gave Romanian Land Forces officers a free hand to discriminate against Jewish recruits.

[43][53] Like Arghezi and Vinea, Costin experimented with satirical genres, his sketch story techniques borrowed from 19th century classic Ion Luca Caragiale (Mateiu's father).

According to historian Lucian Boia, Germanophile newspapers had little room for maneuver, given their unpopular agenda: "of little interest, boycotted and with their offices once in a while assaulted by the 'indignant' public, [they] could never have supported themselves without an infusion of German money.

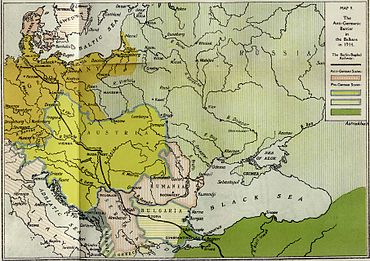

[67] Shortly after the Sarajevo Assassination, which offered the Central Powers a casus belli, Seara circulated rumors about the contradictions between Austrians and Hungarian subjects of the double monarchy.

[77] According to one account, Fleva had earlier been approached to take over as Seara manager by German envoys Brociner and Hilmar von dem Bussche-Haddenhausen, but, realizing the implications, had refused.

According to literary historian Paul Cernat, the ideological ambiguity and conjectural alliances between socialists and conservatives was motivated by a common enemy, the pro-Entente and "plutocratic" National Liberal Party.

[82] The independent socialist Felix Aderca, later known as a novelist, expanded on his earlier theoretical articles for Noua Revistă Română, depicting the German Empire as the "progressive" actor in the war.

On October 6, 1914, Dodan saluted the Social Democratic Party of Romania for organizing internationalist peace rallies, as "emerging from the mind and soul of the entire Romanian people".

Seara and Minerva followed the principles of Marghiloman, who had reached the conclusion that the Entente did not in fact support the disestablishment of Austria-Hungary, and who postulated that Russification in Bessarabia was more serious than Magyarization in Transylvania.

[93] Gorun spoke of any alliance with Russia as dangerous and absurd; the implication of such a move, he argued, caught Transylvanian Romanians in a pincer and also meant Romania's subjugation to the Russian Empire.

Expressing regret that "most civilized" France stood by the world's "most savage, most ignorant and bloodiest oligarchy", "the Russia of pogroms and assassinations", he deemed Romania's overtures toward the Tsarist regime a "national crime".

[80] An unusually vast and, according to Boia, naïve project was sketched by the Bessarabian-born Nour, who claimed that, even if granted a military victory, Austria-Hungary would still crumble into "developed nations".

[99] He speculated that a late entry into the war could also bring Romania possession of Bessarabia, large swathes of Ukraine, and the Odessa harbor; and even that, once victorious against the Entente, the Central Powers would award her an extra-European colonial empire.

[102] The newspaper's wrong bet on a German victory on the Western Front was strained by Alexis Nour who, in April 1916, wrote that a French capitulation would inevitably follow the Battle of Verdun.

[103] When the German and Austrian troops invaded southern Romania, forcing the Ententist government to flee for Iași, some of Seara's former staff remained in Bucharest and chose the path of collaborationism.

[106] Avram Steuerman-Rodion was drafted into the Romanian Land Forces as a medic, earning distinction, but returned to Germanophile journalism after Romania sealed the separate peace of 1918; the victim of clinical depression, he committed suicide in autumn.

[114] As an additional contribution to Romanian literature, Seara's popularization of the expression craii de Curtea-Veche may have inspired Mateiu Caragiale in writing his celebrated 1929 novel.