Northern Virginia campaign

Confederate General Robert E. Lee followed up his successes of the Seven Days Battles in the Peninsula campaign by moving north toward Washington, D.C., and defeating Maj. Gen. John Pope and his Army of Virginia.

Historian John J. Hennessy wrote that "Lee may have fought cleverer battles, but this was his greatest campaign.

"[4] I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies, from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary, and to beat him to when he was found; whose policy has been to attack and not defense.... Let us look before us, and not behind.

After the collapse of McClellan's Peninsula campaign in the Seven Days Battles of June, President Abraham Lincoln appointed John Pope to command the newly formed Army of Virginia.

Pope did not endear himself to his subordinate commanders—all three selected as corps commanders technically outranked him—or to his junior officers, by his boastful orders that implied Eastern soldiers were inferior to their Western counterparts.

John P. Hatch and George D. Bayard were attached directly to the three infantry corps, a lack of centralized control that had negative effects in the campaign.

David R. Jones and Lafayette McLaws continued in command of their divisions, both of which had been part of Magruder's Army of the Peninsula.

[8] Pope's mission was to fulfill a few objectives: protect Washington and the Shenandoah Valley, and draw Confederate forces away from McClellan by moving in the direction of Gordonsville.

[9] Pope started on the latter by dispatching cavalry to break the Virginia Central Railroad connecting Gordonsville, Charlottesville, and Lynchburg.

The cavalry under Hatch got off to a slow start and found that Stonewall Jackson had already occupied Gordonsville on July 19 with over 14,000 men.

For the first time, the Union intended to pressure the civilian population of the Confederacy by bringing some of the hardships of war directly to them.

5 directed the army to "subsist upon the country," reimbursing farmers with vouchers that were payable after the war only to "loyal citizens of the United States."

Pope ordered that any house from which gunfire was aimed at Union troops be burned and the occupants treated as prisoners of war.

These orders were substantially different from the war philosophy of Pope's colleague McClellan, which undoubtedly caused some of the animosity between the two men during the campaign.

Coming through the Hampton Roads area in Union custody, Mosby observed significant naval transport activity and deduced that Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's troops, who had fought in North Carolina, were being shipped to reinforce Pope.

On August 3, General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck directed McClellan to begin his final withdrawal from the Peninsula and to return to Northern Virginia to support Pope.

He was informed by Halleck of the plan to link up with McClellan's army, but rather than waiting for this to occur, he moved some of his forces to a position near Cedar Mountain, from whence he could launch cavalry raids on Gordonsville.

Jackson advanced to Culpeper Court House on August 7, hoping to attack one of Pope's corps before the rest of the army could be concentrated.

[14] On August 9, Nathaniel Banks's corps attacked Jackson at Cedar Mountain, gaining an early advantage.

His plan was to send his cavalry under Stuart, followed by his entire army, north to the Rapidan River on August 18, screened from view by Clark's Mountain.

Stuart's raid demonstrated that the Union right flank was vulnerable to a turning movement, although river flooding brought on by heavy rains would make this difficult.

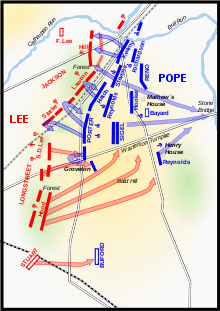

Lee's new plan in the face of all these additional forces outnumbering him was to send Jackson and Stuart with half of the army on a flanking march to cut Pope's line of communication, the Orange & Alexandria Railroad.

[21] On the evening of August 26, after passing around Pope's right flank via Thoroughfare Gap, Jackson's wing of the army struck the Orange & Alexandria Railroad at Bristoe Station and before daybreak August 27 marched to capture and destroy the massive Union supply depot at Manassas Junction.

On August 27, Jackson routed the New Jersey Brigade of the VI Corps near Bull Run Bridge, mortally wounding its commander George W. Taylor.

This seemingly inconsequential action virtually ensured Pope's defeat during the battles of August 29–30 because it allowed the two wings of Lee's army to unite on the Manassas battlefield.

[25] Making a wide flanking march, Jackson hoped to cut off the Union retreat from Bull Run.

[26] The northern Virginia campaign had been expensive for both sides, although Lee's smaller army spent its resources more carefully.

Military historian John J. Hennessy described it as Lee's greatest campaign, the "happiest marriage of strategy and tactics he would ever attain."

Longstreet's attack on August 30, "timely, powerful, and swift, would come as close to destroying a Union army as any ever would.

With Pope no longer a threat and McClellan reorganizing his command, Lee turned his army north on September 4 to cross the Potomac River and invade Maryland, initiating the Maryland campaign and the battles of Harpers Ferry, South Mountain, and Antietam.