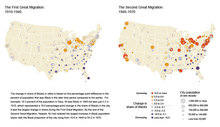

Second Great Migration (African American)

In the Second Great Migration, not only the Northeast and Midwest continued to be the destination of more than 5 million African Americans, but also the West as well, where cities like Los Angeles, Oakland, Phoenix, Portland, and Seattle offered skilled jobs in the defense industry.

The newcomers became permanent residents, building up black political influence, strengthening civil rights organizations such as the NAACP, calling for antidiscrimination legislation.

[citation needed] The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 significantly influenced the Second Great Migration by reshaping the economic dynamics of the Southern United States.

It was actually the cornerstone of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, aimed at alleviating the economic hardships faced by American farmers during the Great Depression.

The act aimed to increase agricultural prices by reducing production, resulting in land consolidation and technological advancements that displaced a significant number of rural workers.

[7] The lack of opportunities in the agricultural sector, combined with ongoing racial segregation and discrimination, pushed African Americans to seek better prospects in Northern cities.

[6] The rapid mobilization of resources and weapons during World War II prompted many African Americans to migrate to Northern and Western cities in search of jobs in the booming munitions industry.

While the Northern black communities such as Chicago and New York City were already well-established from the first Great Migration, relocating to the West was a new destination for the migrants in places like the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, Portland, Phoenix, and the Puget Sound region in Washington.

This urban spatial segregation led to the creation of racially homogeneous areas in cities that saw large amounts of African American migration.

[9] In order to exploit the poor financial situation many migrants were in, areas of low income housing were established in places city planners wanted them to live.

The fear of racially motivated violence and discrimination also served to isolate communities of minorities as they sought collective security and nondiscriminatory treatment close to home.

Another obstacle facing migrating blacks were the discriminatory housing laws that were put in place to counteract progressive legislation following World War II.

The food, music and even the discriminatory white police presence in these neighborhoods were all imported to a certain extent from the collective experiences of the highly concentrated African American migrants.