Second Triumvirate

People Events Places The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created at the end of the Roman republic for Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power.

Constituted by the lex Titia, the triumvirs were given broad powers to make or repeal legislation, issue judicial punishments without due process or right of appeal, and appoint all other magistrates.

The triumvirate, formed in the aftermath of a conflict between Antony and the senate, emerged as a force to reassert Caesarian control over the western provinces and wage war on the liberatores led by the men who assassinated Julius Caesar.

[1] Following the assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC, there was initially a settlement reached between the perpetrators, who styled themselves liberatores, and remaining Caesarian supporters.

[8] Antony also sought later in the year to isolate Cicero politically, as the eloquent ex-consul was prestigious and on friendly terms with large portions of the aristocracy.

In December 44 BC, Cicero induced the senate to honour Octavian's efforts and to support the existing governors of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul in retaining their provinces against Antony.

[18] They received power to issue legally binding edicts,[19] were granted imperium maius which permitted them to overrule the ordinary provincial governors and to take credit for their victories,[20][21] and to act sine provocatione (without right of appeal).

[26] Some three hundred senators and 2,000 equites were then killed;[27] some victims escaped to Macedonia or Sicily (held by Brutus and Sextus Pompey, respectively) or were able to plead successfully for clemency.

Persons on the proscription lists had their properties confiscated and sold; freelance assassins, bounty hunters, and informers received cash rewards for aiding in the killings.

Octavian dispatched Quintus Salvius Salvidienus Rufus against Sextus Pompey's base of operations in Sicily, resulting in a bloody but indecisive battle near Messana.

[41] In the preparations for war, however, Antony found most of the east largely sucked dry by the previous armies of Dolabella, Cassius, and Brutus.

[42] Moving down the Mediterranean coast, Antony confirmed a number of rulers – in spite of their previous support for the liberatores or for Parthia – in Palestine and called Cleopatra to attend to him in Cilicia.

While ancient writers speculated on Antony being manipulated by the Egyptian queen, it is more likely in this period he was merely attempting to strengthen Cleopatra's position in Egypt as part of his policy of favouring strong allied monarchs.

But public opinion soured when they also announced new higher taxes amid further disruption of grain ships from Sextus' fleet.

[53] While in Rome, they also secured the senate's rubber stamp for a required dispensation for Octavia's marriage (she was not yet out of mourning for her previous husband) and for triumviral political and territorial settlements generally.

[54] The dynasts also negotiated peace with Sextus Pompey at Misenum in the summer of 39 BC: they confirmed him in Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, and the Peloponnese for five years.

[56] While Antony was in Italy, his lieutenant Publius Ventidius scored major victories against the Parthian invasion of Asia Minor: he defeated Labienus' forces and presumably had him killed.

Agrippa, serving as consul in 37 BC, built a large harbour (the portus Julius) to train and supply troops against Sextus in Sicily.

He was then abandoned by Artavasdes, the Armenian king; Antony, while successful in some defences, was unable to effectively counter the swift Parthian cavalry.

After accepting the surrender of Sextus Pompey's legions, he attempted to negotiate with Octavian to exchange Sicily and Africa for his old provinces of Narbonensis and Spain.

In a political climate which blamed the civil wars on a collapse of public morality, Octavian was able to link Antony with oriental immorality under Cleopatra's influence.

Octavian's ally Agrippa also engaged in renovations of the sewers and aqueducts; and during a term as aedile in 33 BC, sponsored spectacular games and public donations.

Arriving in Athens, Antony divorced Octavia; the choice of removing his Roman wife to stay with his Egyptian mistress alienated Italian public opinion.

Opening it, Octavian allegedly found that Antony planned to be buried in Alexandria, would recognise Caesarion as Caesar's son, and give large portions of Roman lands to his children with Cleopatra.

[87] Antony's forces in Greece provoked panic in Italy; Octavian, no longer calling himself triumvir (but retaining his provincial commands) organised defence of the peninsula.

[88] Early in the campaigning season of 31 BC, Agrippa launched a series of surprise attacks on the western Greek harbours under Antony's control.

[91] After a number of defections to Octavian – both Roman governors and client kings – through the winter of 31 and 30 BC, Antony's remaining forces were only those in the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

[105] While the mere operation of the republic's institutional machinery did not represent a free state, the triumvirs made a show of following traditional legal niceties.

[107] Most especially, the triumvirs' powers to appoint all provincial governors served as part of the division between military and civic provinces later adopted in Augustus' political settlements.

Many of the great works of Latin literature were produced in this unstable period, such as Horace's Epodes and Satires, Virgil's Eclogues and Georgics, and the histories of Sallust and Asinius Pollio.

|

Sextus Pompey

Brutus & Cassius

Rome's client kingdoms

Ptolemaic Egypt

|

|

Antony

Lepidus

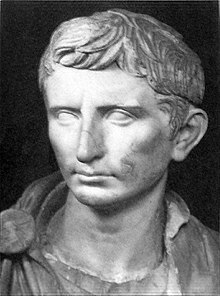

Octavian

Triumvirs collectively

|