Section 92 of the Constitution of Australia

Some thirty years on, the student who is confronted with the heightened confusion arising from the additional case law ending with Miller v. TCN Channel Nine[3] would be even more encouraged to despair of identifying the effect of the constitutional guarantee.

[4]The full text of Section 92 is as follows: On the imposition of uniform duties of customs, trade, commerce, and intercourse among the States, whether by means of internal carriage or ocean navigation, shall be absolutely free.

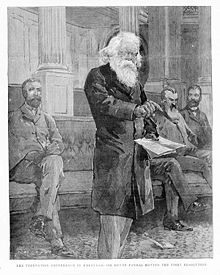

[1]Before the beginning of the first Constitutional Convention in Sydney in 1891, Sir Henry Parkes originally proposed the following resolution: That the trade and intercourse between the Federated Colonies, whether by means of land carriage or coastal navigation, shall be free from the payment of Customs Duties, and from all restrictions whatsoever, except from such regulations as may be necessary for the conduct of business.

[5] At the Convention itself, the wording of the resolution that was presented was altered to read: That the trade and intercourse between the Federated Colonies, whether by means of land carriage or coastal navigation, shall be absolutely free.

[9] At the Sydney session, Barton intended to amend the proposal, by declaring that "trade and intercourse throughout the Commonwealth is not to be restricted or interfered with by any taxes, charges or imposts" but no decision was taken at that time.

"It was typical of the situation that Sir George Reid, the New South Wales Premier famous for the equivocations on both federation and free trade, should have praised the section as 'a little bit of layman's language.'

...The notions of absolutely free trade and commerce and absolutely free intercourse are quite distinct and neither the history of the clause nor the ordinary meaning of its words require that the content of the guarantee of freedom of trade and commerce be seen as governing or governed by the content of the guarantee of freedom of intercourse.

[17] Lord Wright of Durley, seven years after his retirement from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, expressed the opinion that s. 92 ought to have been construed purely as a fiscal clause.

In making this ruling, the Privy Council affirmed the observation of Evatt and McTiernan JJ in the High Court: We are definitely of opinion that sec.

The expression "free trade" commonly signified in the nineteenth century, as it does today, an absence of protectionism, that is, the protection of domestic industries against foreign competition....[4]Accordingly, s. 92 prohibits the Commonwealth and the States from imposing burdens on interstate trade and commerce which: Because of the new approach in Cole,[4] the High Court will be less concerned with issues of policy, and, therefore, will not be concerned with the following matters where there is no protectionist purpose or effect:[30] Accordingly, in Barley Marketing Board (NSW) v Norman, it was held that the compulsory sale of barley to a State marketing board did not contravene s. 92, as the grain had not yet entered interstate trade.

[32]The second step of the Castlemaine test was modified in 2008 in Betfair Pty Limited v Western Australia,[34] to include the concept of reasonable necessity, which also depends on proportionality:[35] 110.

But, allowing for the presence to some degree of a threat of this nature, a method of countering it, which is an alternative to that offered by prohibition of betting exchanges, must be effective but non-discriminatory regulation.

(as he then was) to determine whether a law infringes the s. 92 guarantee to free intercourse:[37] In 2020, Western Australia closed its border to interstate travellers due to the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Mining magnate Clive Palmer challenged the border closure after being refused entry to the state, citing Section 92 of the Constitution.

[38] In the same week, the court also rejected a challenge against the government lockdowns in Melbourne, finding that there was no 'implied freedom of movement (within a state) in the Constitution'.