Secularism in Turkey

This centralized progressive approach was seen as necessary not only for the operation of the Turkish government but also to avoid a cultural life dominated by superstition, dogma, and ignorance.

[6] The Ottoman-appointed governor collected taxes and provided security, while the local religious or cultural matters were left to the regional communities to decide.

By the turn of the 19th century the Ottoman ruling elite recognized the need to restructure the legislative, military and judiciary systems to cope with their new political rivals in Europe.

When the millet system started to lose its efficiency due to the rise of nationalism within its borders, the Ottoman Empire explored new ways of governing its territory composed of diverse populations.

Many of these reforms affected every aspect of Turkish life, moving to erase the legacy of dominance long held by religion and tradition.

The inclusion of reference to laïcité into the constitution was achieved by an amendment on 5 February 1937, a move regarded as the final act in the project of instituting complete separation between governmental and religious affairs in Turkey.

Some (David Lepeska, Svante Cornell) have complained that under Erdoğan that role has "largely been turned on its head",[17] with the Diyanet, now greatly increased in size, promoting Islam in Turkey, specifically a certain type of conservative Islam—issuing fatawa forbidding such activities as "feeding dogs at home, celebrating the western New Year, lotteries, and tattoos";[18] and projecting this "Turkish Islam"[17] abroad.

[19][20] In education, the AKP government pursued the explicit policy agenda of Islamization to "raise a devout generation" against secular resistance,[21][22] in the process causing many non-religious citizens of Turkey to lose their jobs and schooling.

[26] One explanation for the replacement of secularist policies[27] in Turkey is that business interests who felt threatened by socialism saw Islamic values as "best suited to neutralize any challenges from the left to capitalist supremacy.

[29][30][31] After Erdoğan stated his desire to "raise a religious youth," politicians of all parties condemned his statements as abandoning Turkish values.

[citation needed] The system which tried to be established in the constitution sets out to found a unitary nation-state based on the principles of secular democracy.

[citation needed] The Turkish Constitution recognizes freedom of religion for individuals whereas identified religious communities are placed under the protection of state.

[33][34] On 22 July 2007, it was reported that the more religiously conservative ruling party won a larger than expected electoral victory in the snap general election.

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has broken with secular tradition, by speaking out in favor of limited Islamism and against the active restrictions,[citation needed] instituted by Atatürk on wearing the Islamic-style head scarves in government offices and schools.

The Republic Protests (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Mitingleri) were a series of peaceful mass rallies that took place in the spring of 2007 in support of the Kemalist ideals of state secularism.

[citation needed] Groups that have expressed dissatisfaction with this situation include a variety of non-governmental Sunni / Hanafi groups (such as the Nurcu movement), whose interpretation of Islam tends to be more activist; and the non-Sunni (Alevi), whose members tend to resent supporting the Sunni establishment with their tax money (whereas the Turkish state does not subsidize Alevi religious activities).

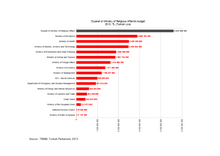

The government agency known as the "Presidency of Religious Affairs" or Diyanet[42] draws on tax revenues collected from all Turkish citizens, but finances only Sunni worship.

[43] For example, Câferî (Ja'fari) Muslims (mostly Azeris) and Alevi-Bektashi (mostly Turkmen) participate in the financing of the mosques and the salaries of Sunni imams, while their places of worship, which are not officially recognized by the State, do not receive any funding.

[citation needed] Theoretically, Turkey, through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), recognizes the civil, political and cultural rights of non-Muslim minorities.

In practice, Turkey only recognizes Greek, Armenian and Jewish religious minorities without granting them all the rights mentioned in the Treaty of Lausanne.

In 1999, the ban on headscarves in the public sphere hit the headlines when Merve Kavakçı, a newly elected MP for the Virtue Party was prevented from taking her oath in the National Assembly because she wore a headscarf.

[38] In 2022, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has suggested the constitutional change to guarantee the right to wear a headscarf in the civil service, schools, and universities should be decided through a referendum.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) reports that in late 2005, the Administrative Supreme Court ruled that a teacher was not eligible for a promotion in her school because she wore a headscarf outside of work (Jan. 2007).

An immigration counsellor at the Embassy of Canada in Ankara stated on 27 April 2005 correspondence with the Research Directorate that public servants are not permitted to wear a headscarf while on duty, but headscarved women may be employed in the private sector.

The professor did add, however, that headscarved women generally experience difficulty in obtaining positions as teachers, judges, lawyers, or doctors in the public service (ibid.).

The London-based Sunday Times reports that while the ban is officially in place only in the public sphere, many private firms similarly avoid hiring women who wear headscarves (6 May 2007).

Nevertheless, MERO reports that under Turkey's current administration, seen by secularists to have a hidden religious agenda,[62][63] doctors who wear headscarves have been employed in some public hospitals.