Ostracod

[9] Freshwater ostracods have even been found in Baltic amber of Eocene age, having presumably been washed onto trees during floods.

[10] Ostracods have been particularly useful for the biozonation of marine strata on a local or regional scale, and they are invaluable indicators of paleoenvironments because of their widespread occurrence, small size, easily preservable, generally moulted, calcified bivalve carapaces; the valves are a commonly found microfossil.

A find in Queensland, Australia, in 2013, announced in May 2014, at the Bicentennary Site in the Riversleigh World Heritage area, revealed both male and female specimens with very well preserved soft tissue.

It was assessed that the fossilisation was achieved within several days, due to phosphorus in the bat droppings of the cave where the ostracods were living.

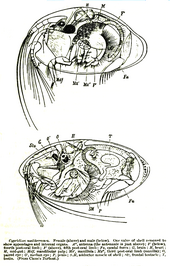

[12] The body of an ostracod is encased by a carapace originating from the head region, and consists of two valves superficially resembling the shell of a clam.

In Manawa, an ostracod in the order Palaeocopida, the carapace originates as a single element and during growth folds at the midline.

The two "rami", or projections, from the tip of the tail point downward and slightly forward from the rear of the shell.

[17][18][19]: 40 All ostracods have a pair of "ventilatory appendages" that beat rhythmically, which create a water current between the body and the inner surface of the carapace.

Podocopa, the largest subclass, have no gills, heart or circulatory system, so the gas exchange take place all over the surface.

Certain other larger members of Myodocopa, even if they don't have gills, have a circulatory system where hemolymph sinuses absorbs oxygen through special areas on the inner wall of the carapace.

[17][25][26] Platycopida was assumed to be completely eyeless, but two species, Keijcyoidea infralittoralis and Cytherella sordida, have been found to both possess a nauplius eye too.

[37] Representatives living in terrestrial habitats are also found in all three freshwater groups,[38] such as genus Mesocypris which is known from humid forest soils of South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

[41] Non-marine species have been found to live in sulfidic cave ecosystems such as the Movile Cave, deep groundwaters, hypersaline waters, acidic waters with pH as low as 3.4, phytotelmata in plants like bromeliads, and in temperatures varying from almost freezing to more than 50 °C in hot springs.

[41] Many Cyprididae occur in temporary water bodies and have drought-resistant eggs, mixed/parthenogenetic reproduction, and the ability to swim.

Mating typically occurs during swarming, with large numbers of females swimming to join the males.

[17] Superfamily Darwinuloidea was assumed to have reproduced asexually for the last 200 million years, but rare males have since been discovered in one of the species.

[45] In the subclass Myodocopa, all members of the order Myodocopida have brood care, releasing their offspring as first instars, allowing a pelagic lifestyle.

In the order Halocyprida the eggs are released directly into the sea, except for a single genus with brood care.

The light from these ostracods, called umihotaru in Japanese, was sufficient to read by but not bright enough to give away troops' position to enemies.

This bioluminiscent courtship display has only evolved once in ostracods, in a cypridinid group named Luxorina that originated at least 151 million years ago.

[62][63] Ostracods with bioluminescent courtship show higher rates of speciation than those who simply use light as protection against predators.