Duality (mathematics)

For example, Desargues' theorem is self-dual in this sense under the standard duality in projective geometry.

For instance, linear algebra duality corresponds in this way to bilinear maps from pairs of vector spaces to scalars, the duality between distributions and the associated test functions corresponds to the pairing in which one integrates a distribution against a test function, and Poincaré duality corresponds similarly to intersection number, viewed as a pairing between submanifolds of a given manifold.

[4] From a category theory viewpoint, duality can also be seen as a functor, at least in the realm of vector spaces.

The three properties of the dual cone carry over to this type of duality by replacing subsets of

Instead, such dualities reveal a close relation between objects of seemingly different nature.

Conversely, to any such subgroup H ⊆ G there is the fixed field KH consisting of elements fixed by the elements in H. Compared to the above, this duality has the following features: Given a poset P = (X, ≤) (short for partially ordered set; i.e., a set that has a notion of ordering but in which two elements cannot necessarily be placed in order relative to each other), the dual poset Pd = (X, ≥) comprises the same ground set but the converse relation.

Familiar examples of dual partial orders include A duality transform is an involutive antiautomorphism f of a partially ordered set S, that is, an order-reversing involution f : S → S.[9][10] In several important cases these simple properties determine the transform uniquely up to some simple symmetries.

A kind of geometric duality also occurs in optimization theory, but not one that reverses dimensions.

A linear program may be specified by a system of real variables (the coordinates for a point in Euclidean space

In general, this yields a true duality only for specific choices of D, in which case X* = Hom (X, D) is referred to as the dual of X.

For example, if K is the field of real or complex numbers, any positive definite bilinear form gives rise to such an isomorphism.

Another application of inner product spaces is the Hodge star which provides a correspondence between the elements of the exterior algebra.

In this guise, the duality inherent in the inner product space exchanges the role of magnetic and electric fields.

As a consequence of the dimension formula of linear algebra, this space is two-dimensional, i.e., it corresponds to a line in the projective plane associated to

The explicit formulas in duality in projective geometry arise by means of this identification.

There are several notions of topological dual space, and each of them gives rise to a certain concept of duality.

However, in many circumstances the opposite categories have no inherent meaning, which makes duality an additional, separate concept.

Further notions displaying related by such a categorical duality are projective and injective modules in homological algebra,[20] fibrations and cofibrations in topology and more generally model categories.

[24] In a number of situations, the two categories which are dual to each other are actually arising from partially ordered sets, i.e., there is some notion of an object "being smaller" than another one.

An example is the standard duality in Galois theory mentioned in the introduction: a bigger field extension corresponds—under the mapping that assigns to any extension L ⊃ K (inside some fixed bigger field Ω) the Galois group Gal (Ω / L) —to a smaller group.

[25] The collection of all open subsets of a topological space X forms a complete Heyting algebra.

In analysis, problems are frequently solved by passing to the dual description of functions and operators.

A conceptual explanation of the Fourier transform is obtained by the aforementioned Pontryagin duality, applied to the locally compact groups R (or RN etc.

The dualizing character of Fourier transform has many other manifestations, for example, in alternative descriptions of quantum mechanical systems in terms of coordinate and momentum representations.

[27] Poincaré duality can also be expressed as a relation of singular homology and de Rham cohomology, by asserting that the map (integrating a differential k-form over a (2n − k)-(real-)dimensional cycle) is a perfect pairing.

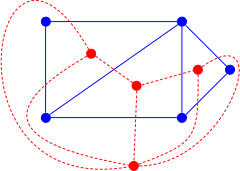

Poincaré duality also reverses dimensions; it corresponds to the fact that, if a topological manifold is represented as a cell complex, then the dual of the complex (a higher-dimensional generalization of the planar graph dual) represents the same manifold.

The same duality pattern holds for a smooth projective variety over a separably closed field, using l-adic cohomology with Qℓ-coefficients instead.

[30] With increasing level of generality, it turns out, an increasing amount of technical background is helpful or necessary to understand these theorems: the modern formulation of these dualities can be done using derived categories and certain direct and inverse image functors of sheaves (with respect to the classical analytical topology on manifolds for Poincaré duality, l-adic sheaves and the étale topology in the second case, and with respect to coherent sheaves for coherent duality).

The absolute Galois group G(Fq) of a finite field, for example, is isomorphic to

Therefore, the perfect pairing (for any G-module M) is a direct consequence of Pontryagin duality of finite groups.