Sellmeier equation

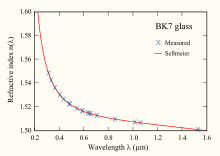

Analytically, this process is based on approximating the underlying optical resonances as dirac delta functions, followed by the application of the Kramers-Kronig relations.

[2] However, close to each absorption peak, the equation gives non-physical values of n2 = ±∞, and in these wavelength regions a more precise model of dispersion such as Helmholtz's must be used.

If all terms are specified for a material, at long wavelengths far from the absorption peaks the value of n tends to where εr is the relative permittivity of the medium.

Sometimes the Sellmeier equation is used in two-term form:[7] Here the coefficient A is an approximation of the short-wavelength (e.g., ultraviolet) absorption contributions to the refractive index at longer wavelengths.

Other variants of the Sellmeier equation exist that can account for a material's refractive index change due to temperature, pressure, and other parameters.

Analytically, the Sellmeier equation models the refractive index as due to a series of optical resonances within the bulk material.

Its derivation from the Kramers-Kronig relations requires a few assumptions about the material, from which any deviations will affect the model's accuracy: From the last point, the complex refractive index (and the electric susceptibility) becomes: The real part of the refractive index comes from applying the Kramers-Kronig relations to the imaginary part: Plugging in the first equation above for the imaginary component: The order of summation and integration can be swapped.