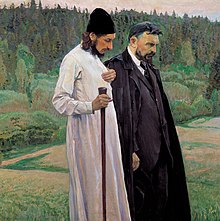

Sergei Bulgakov

[3] Bulgakov is best known for his teaching about Sophia the Wisdom of God, which received mixed reception; it was condemned by the Moscow Patriarchate in 1935, but without accusations of heresy.

[7][8][9] Metropolitan Macarius Bulgakov (1816–1882), one of the major Eastern Orthodox theologians of his days, and one of the most important Russian church historians, was a distant relative.

[11] After Bulgakov quit the seminary, he entered Yelets Classical Gymnasium to prepare for the law faculty of the Imperial Moscow University.

[6] In the same year, he published a review of Karl Marx's unfinished third volume of Das Kapital, and authored an essay in 1896, "On the Regularity of Social Phenomena."

The thesis ended by declaring that Marx's analysis of capitalism, limited by features of the English economy, did not integrate this system with an economic theory of agriculture, and was not a realistic, universal account of capitalist society.

Another major factor in his eventual separation from the Union of Liberation was the increasingly anti-Christian direction being championed by leading representatives of left-liberal politics.

However, Bulgakov also did not appreciate the increasing radicalization of the leftists in Russia and their abandonment of Russian Orthodoxy in favor of a purely secular state; on the contrary, it caused him to uphold the positive value of governance by Nicholas II, even as he continued to detest him, accusing him of promoting the revolution and bringing about the demise of the royal family.

In his work during this period, he transitioned from lectures and articles on topics of religion and culture (the most important of which he collected in the two-volume book Two Cities, published 1911) to original philosophical developments.

Bulgakov rejected the October Revolution and responded to it with the dialogues At the Feast of the Gods ("На пиру богов", 1918), written in a style similar to the Three Talks of Vladimir Solovyov.

[6] In 1922, Bulgakov was included in a list of scientific and cultural figures subject to deportation, compiled by the State Political Directorate on the initiative of Vladimir Lenin.

"[19] In 1935, after the publication of his book, Lamb of God, Bulgakov was accused of teachings contrary to Orthodox dogma by the Metropolitan Sergius I of Moscow, who recommended his exclusion from the Church until he amended his "dangerous" views.

Metropolitan Evlogy set up a committee in Paris to investigate Bulgakov's orthodoxy, which reached a preliminary conclusion that his thought was free from heresy.

He served early liturgies in the chapel in the name of the Dormition of the Mother of God, and continued to lecture on dogmatic theology, carry out his pastoral care, and write.

Bulgakov condemned the basic view of political economy of the early 20th century, according to which the growth of material needs is the fundamental principle of normal economic development.

Bulgakov viewed the inability to be satisfied with the increase in external material benefits and to come to terms with the deep-rooted forms of social untruth, the desire for universal human ideals, and the insatiable need for conscious and effective religious faith as the most characteristic and happiest features of the Russian spirit.

He set out to show in the history of agrarian evolution the universal applicability of Karl Marx's law of concentration of production, but came to the exact opposite conclusions.

After unsuccessful attempts to use Kant's epistemological precepts in the interests of Marxism, Bulgakov settled on the idea that a solid justification for the guiding principles of personal and public life is possible only by developing unconditional standards in matters of the good, the truth, and beauty.

To him, positive science, with its theory of progress, wanted to absorb both metaphysics and religious faith, but, leaving people in complete uncertainty regarding the future destinies of humanity, it gave them only the dogmatic theology of atheism; a mechanical understanding of the world, subordinating everything to fatal necessity, ultimately turns out to rest on faith.

For Bulgakov, Marxism, as the brightest variety of the religion of progress, inspired its supporters with faith in the imminent and natural arrival of a renewed social system; it was strong not in its scientific, but in its utopian elements, and Bulgakov came to the conviction that progress is not an empirical law of historical development, but a moral task, an absolute religious obligation.

From a moral point of view, parties fighting over worldly goods are quite equivalent, since they are guided not by religious enthusiasm, not by the search for the unconditional and lasting meaning of life, but by ordinary self-love.

According to Bulgakov, the eudaimonic ideal of progress, as a scale for assessing historical development, leads to antimoral conclusions, to the recognition of suffering generations as only a bridge to the future bliss of their descendants.

Bulgakov was one of the main exponents of vekhovstvo, an ideological movement that called on the intelligentsia to "sober up" and move away from "herd morality", "utopianism", and "rabid revolutionism" in favor of the work of spiritual comprehension and a constructive social position.

At the beginning of the First World War, he wrote Slavophile articles and expressed faith in the universal calling and great future of the state.

Later, in the dialogues At the Feast of the Gods and other texts of the revolutionary period, he depicted the fate of Russia as apocalyptic and alarmingly unpredictable, rejecting any recipes and forecasts.

For a short time, Bulgakov believed that Catholicism rather than Orthodoxy would be able to prevent the processes of schism and disintegration that prepared the catastrophe of the nation.

[21] At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Bulgakov became disillusioned with Marxism because he considered it incapable of answering the deep religious needs of the human personality and radically changing it.

In polemics with the tradition of German idealism, Bulgakov refuses to consider reason and thinking as the highest principle, endowed with the exclusive prerogative of connection with God.

Father Sergius's thought developed "from below", from economic issues and philosophical teaching on the economy (Philosophy of Economy) to a general teaching on matter and the world, and, finally, to a comprehensive theological system that provides a final solution to the original problem: rooting the world in God and at the same time directly following Christian revelation and dogma.

Bulgakov concludes that an adequate expression of Christian truth is fundamentally inaccessible to philosophy and is achievable only in the form of dogmatic theology.

[21] According to the memoirs of Archbishop Nathanael (Lvov) [ru]: “Once, in the presence of Metropolitan Anthony [Khrapovitsky], a conversation arose about Father Sergius Bulgakov.