Animal Farm

NPR: 100 Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Books Hugo Award for Best Short Novel (1946) Animal Farm is a satirical allegorical novella, in the form of a beast fable,[1] by George Orwell, first published in England on 17 August 1945.

According to Orwell, Animal Farm reflects events leading up to the Russian Revolution of 1917 and then on into the Stalinist era of the Soviet Union, a period when Russia lived under the Marxist–Leninist ideology of Joseph Stalin.

[7] Orwell suggested the title Union des républiques socialistes animales for the French translation, which abbreviates to URSA, the Latin word for "bear", a symbol of Russia.

[b] It became a great commercial success when it did appear, as international relations and public opinion were transformed as the wartime alliance gave way to the Cold War.

[17] The animal populace of the poorly run Manor Farm near Willingdon, England, is ripened for rebellion by neglect at the hands of the irresponsible and alcoholic farmer, Mr. Jones.

Other changes include the Hoof and Horn flag being replaced with a plain green banner and Old Major's skull, which was previously put on display, being reburied.

[43] Furthermore, these two prominent works seem to suggest Orwell's bleak view of the future for humanity; he seems to stress the potential/current threat of dystopias similar to those in Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

This style reflects Orwell's proximity to the issues facing Europe at the time and his determination to comment critically on Stalin's Soviet Russia.

In the preface of a 1947 Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm, he explained how escaping the communist purges in Spain taught him "how easily totalitarian propaganda can control the opinion of enlightened people in democratic countries".

[50] Homage to Catalonia sold poorly; after seeing Arthur Koestler's best-selling Darkness at Noon about the Moscow Trials, Orwell decided that fiction would be the best way to describe totalitarianism.

The booklet included instructions on how to quell ideological fears of the Soviet Union, such as directions to claim that the Red Terror was a figment of Nazi imagination.

[52] In the preface, Orwell described the source of the idea of setting the book on a farm:[50] I saw a little boy, perhaps ten years old, driving a huge carthorse along a narrow path, whipping it whenever it tried to turn.

[53] Orwell initially encountered difficulty getting the manuscript published, largely due to fears that the book might upset the alliance between Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union.

The publisher Jonathan Cape, who had initially accepted Animal Farm, subsequently rejected the book after an official at the British Ministry of Information warned him off[57] – although the civil servant who it is assumed gave the order was later found to be a Soviet spy.

Frederic Warburg also faced pressures against publication, even from people in his own office and from his wife Pamela, who felt that it was not the moment for ingratitude towards Stalin and the Red Army,[60] which had played a major part in defeating Adolf Hitler.

A translation in Ukrainian, which was produced in Germany, was confiscated in large part by the American wartime authorities and handed over to the Soviet repatriation commission.

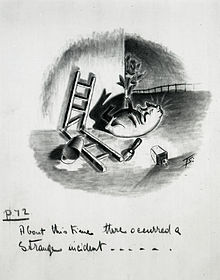

[e] In October 1945, Orwell wrote to Frederic Warburg expressing interest in pursuing the possibility that the political cartoonist David Low might illustrate Animal Farm.

Things are kept right out of the British press, not because the Government intervenes but because of a general tacit agreement that "it wouldn't do" to mention that particular fact.Although the first edition allowed space for the preface in the author's proof, it was not included, and the page numbers had to be renumbered at the last minute.

[63] In 1972, Ian Angus found the original typescript titled "The Freedom of the Press", and Bernard Crick published it, together with his introduction, in The Times Literary Supplement on 15 September 1972 as "How the essay came to be written".

Soule believed that the animals were not consistent enough with their real-world inspirations, and said, "It seems to me that the failure of this book (commercially it is already assured of tremendous success) arises from the fact that the satire deals not with something the author has experienced, but rather with stereotyped ideas about a country which he probably does not know very well".

[51] The Information Research Department, a secret Cold War propaganda agency of the British government, translated the book into various languages such as Arabic.

Soon after, Napoleon and Squealer partake in activities associated with the humans (drinking alcohol, sleeping in beds, trading), which were explicitly prohibited by the Seven Commandments.

Squealer is employed to alter the Seven Commandments to account for this humanisation, an allusion to the Soviet government's revising of history to exercise control of the people's beliefs about themselves and their society.

[78] In a preface for a 1947 Ukrainian edition, he stated, "for the past ten years I have been convinced that the destruction of the Soviet myth was essential if we wanted a revival of the socialist movement.

[29] The pigs' appropriation of milk and apples for their own use, "the turning point of the story" as Orwell termed it in a letter to Dwight Macdonald,[78] stands as an analogy for the crushing of the left-wing 1921 Kronstadt revolt against the Bolsheviks,[78] and the difficult efforts of the animals to build the windmill suggest the various five-year plans.

The puppies controlled by Napoleon parallel the nurture of the secret police in the Stalinist structure, and the pigs' treatment of the other animals on the farm recalls the internal terror faced by the populace in the 1930s.

[f] Other connections that writers have suggested illustrate Orwell's telescoping of Russian history from 1917 to 1943,[84][g] including the wave of rebelliousness that ran through the countryside after the Rebellion, which stands for the abortive revolutions in Hungary and Germany (Ch.

V), parallelling "the two rival and quasi-Messianic beliefs that seemed pitted against one another: Trotskyism, with its faith in the revolutionary vocation of the proletariat of the West; and Stalinism with its glorification of Russia's socialist destiny";[85] Napoleon's dealings with Whymper and the Willingdon markets (Ch.

[88] A theatrical version, with music by Richard Peaslee and lyrics by Adrian Mitchell, was staged at the National Theatre London on 25 April 1984, directed by Peter Hall.

Tamsin Greig narrated, and the cast included Nicky Henson as Napoleon, Toby Jones as the propagandist Squealer, and Ralph Ineson as Boxer.