Seven Days Battles

Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from Richmond and into a retreat down the Virginia Peninsula.

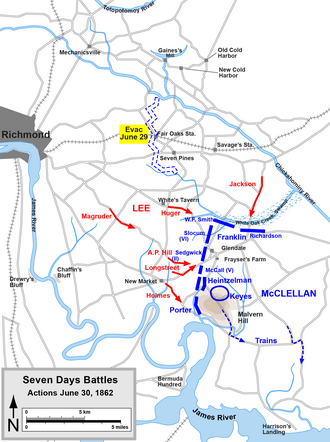

Lee's final opportunity to intercept the Union Army was at the Battle of Glendale on June 30, but poorly executed orders and the delay of Stonewall Jackson's troops allowed his enemy to escape to a strong defensive position on Malvern Hill.

At the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, Lee launched futile frontal assaults and suffered heavy casualties in the face of strong infantry and artillery defenses.

It started in March 1862, when McClellan landed his army at Fort Monroe and moved northwest, up the Virginia Peninsula beginning in early April.

Lee spent almost a month extending his defensive lines and organizing his Army of Northern Virginia; McClellan accommodated this by sitting passively to his front, waiting for dry weather and roads, until the start of the Seven Days.

Lee hoped that Porter would be overwhelmed from two sides by the mass of 65,000 men, and the two leading Confederate divisions would move on Cold Harbor and cut McClellan's communications with White House Landing.

Although Robinson and Grover made good progress on the left and in the center, Sickles's New Yorkers encountered difficulties moving through their abatis, then through the upper portions of the creek, and finally met stiff Confederate resistance, all of which threw the Federal line out of alignment.

Hill's Light Division was to advance from Meadow Bridge when he heard Jackson's guns, clear the Union pickets from Mechanicsville, and then move to Beaver Dam Creek.

[25] Overall, the battle was a Union tactical victory, in which the Confederates suffered significant casualties and achieved none of their specific objectives due to the seriously flawed execution of Lee's plan.

Several of McClellan's subordinates urged him to attack Magruder's division south of the river, but he feared the vast numbers of Confederates he believed to be before him and refused to capitalize on the overwhelming superiority he actually held on that front.

By early afternoon, he ran into strong opposition where Porter had deployed along Boatswain's Creek; the swampy terrain was a major obstacle to the attack.

However, although McClellan had already planned to shift his supply base to the James River, his defeat unnerved him and he precipitously decided to abandon his advance on Richmond.

)[36] McClellan ordered Keyes's IV Corps to move west of Glendale and protect the army's withdrawal, while Porter was sent to the high ground at Malvern Hill to develop defensive positions.

[38] While Lee's main attack at Gaines's Mill was progressing on June 27, the Confederates south of the Chickahominy performed a reconnaissance in force to determine the location of McClellan's retreating army.

Toombs, a Georgia politician with a disdain for professional officers, instead launched a sharp attack at dusk against Baldy Smith's VI Corps division near Old Tavern at the farm of James M. Garnett.

Two of Anderson's regiments, the 7th and 8th Georgia, preceded Toombs's brigade into the assault and were subjected to a vigorous Federal counterattack by the 49th Pennsylvania and 43rd New York, losing 156 men.

[41] On Sunday, June 29, the bulk of McClellan's army concentrated around Savage's Station on the Richmond and York River Railroad, a Federal supply depot since just before Seven Pines, preparing for a difficult crossing through and around White Oak Swamp.

Stonewall Jackson, commanding three divisions, was to rebuild a bridge over the Chickahominy and head due south to Savage's Station, where he would link up with Magruder and deliver a strong blow that might cause the Union Army to turn around and fight during its retreat.

[44] Initial contact between the armies occurred at 9 a.m. on June 29, a four-regiment fight about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Savage's Station, lasting for about two hours before disengaging.

He was taking time to rebuild bridges over the Chickahominy and he received a garbled order from Lee's chief of staff that made him believe he should stay north of the river and guard the crossings.

Stonewall Jackson moved slowly and spent the entire day north of the creek, making only feeble efforts to cross and attack Franklin's VI Corps in the Battle of White Oak Swamp, attempting to rebuild a destroyed bridge (although adequate fords were nearby), and engaging in a pointless artillery duel.

Holmes's relatively inexperienced troops made no progress against Porter at Turkey Bridge on Malvern Hill, even with the reinforcements from Magruder, and were repulsed by effective artillery fire and by Federal gunboats on the James.

[53] At 2 p.m., as they waited for sounds of Huger's expected attack, Lee, Longstreet, and visiting Confederate President Jefferson Davis were conferring on horseback when they came under heavy artillery fire, wounding two men and killing three horses.

In their first combat experience, the brigade conducted a disorderly but enthusiastic assault, which carried them through the guns and broke through McCall's main line with Jenkins's support, followed up a few hours later by Brig.

Heavy fighting continued until about 8:30 p.m. Longstreet committed virtually every brigade in the divisions under his command, while on the Union side they had been fed in individually to plug holes in the line as they occurred.

Although Jackson's wing of the army and Franklin's corps comprised tens of thousands of men, the action at White Oak Swamp included no infantry activity and was limited to primarily an artillery duel with few casualties.

Malvern Hill was not a tenable position in which to stay, and the Army of the Potomac quickly withdrew to Harrison's Landing, where it was protected by Union gunboats on the James River.

Meanwhile, the equally exhausted Army of Northern Virginia, with no reason to remain in the James bottomlands, pulled back to the Richmond lines to lick its wounds.

McClellan wrote a series of letters to the War Department to argue that he was facing upwards of 200,000 Confederates and that he needed major reinforcements to launch a renewed offensive on Richmond.

Halleck also pointed out that mosquito season was coming up in August–September, and remaining on the swampy Virginia Peninsula at that time of the year would be inviting a disastrous malaria and yellow fever epidemic.