Seven Sleepers

[5] The earliest known version of this story[clarification needed] is found in the writings of the Syriac bishop Jacob of Serugh (c. 450–521), who relies on an earlier Greek source, now lost.

[6] Jacob of Serugh, an Edessan poet-theologian, wrote a homily in verse on the subject of the Seven Sleepers,[7] which was published in the Acta Sanctorum.

[8][5] The pilgrim account De situ terrae sanctae, written between 518 and 531, records the existence of a church dedicated to the sleepers in Ephesus.

These include 104 Latin manuscripts, 40 Greek, 33 Arabic, 17 Syriac, six Ethiopic, five Coptic, two Armenian, one Middle Irish, and one Old English.

It was popularized in the West by Gregory of Tours, in his late 6th-century collection of miracles, De gloria martyrum (Glory of the Martyrs).

[7] Gregory claimed to have gotten the story from "a certain Syrian interpreter" (Syro quidam interpretante), but this could refer to either a Syriac- or Greek-speaker from the Levant.

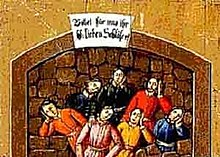

The Seven Sleepers were included in the Golden Legend compilation, the most popular book of the later Middle Ages, which fixed a precise date for their resurrection, AD 478, in the reign of Theodosius[dubious – discuss].

Instead they chose to give their worldly goods to the poor and retire to a mountain cave to pray, where they fell asleep.

At some later time—usually given as during the reign of Theodosius II (408–450)—in AD 447 when heated discussions were taking place between various schools of Christianity about the resurrection of the body in the day of judgement and life after death, a landowner decided to open up the sealed mouth of the cave, thinking to use it as a cattle pen.

The bishop was summoned to interview the sleepers; they told him their miracle story, and died praising God.

[17] The polytheists (mushriks) of Mecca, after consulting with the people of the Book, tested Muhammad by asking him three questions, and Surah Al-Kahf was sent down in answer to them.

The mushriks inquired about the identity of the Sleepers of the Cave, the real story of Khidr, and about Dhu al-Qarnayn.

[20] The Quran says that the sleepers included a dog, which Islamic tradition names as Qitmir, who guarded the entrance of the cave (verse 18).

[5][21] A 6th-century Latin text titled "Pilgrimage of Theodosius"[clarification needed] featured the sleepers as seven people in number, with a dog named Viricanus.

[22][23] Bartłomiej Grysa lists at least seven different sets of names for the sleepers:[8] In Islam no specific number is mentioned.

As the earliest versions of the legend spread out from Ephesus, an early Christian catacomb in that area came to be associated with it, attracting scores of pilgrims.

The Emperor brought marble niches from Western Anatolia as gifts for it, which are preserved inside the Eshab-ı Kehf Kulliye mosque to this day.

The Italian author Andrea Camilleri incorporates the story in his novel The Terracotta Dog in which the protagonist is led to a cave containing the titular watchdog (as described in the Qur'an and called "Kytmyr" in Sicilian folklore) and the saucer of silver coins with which one of the sleepers is to buy "pure food" from the bazaar in Ephesus (Qur'an 18.19).

The Seven Sleepers are symbolically replaced by lovers Lisetta Moscato and Mario Cunich, who were killed in their nuptial bed by an assassin hired by Lisseta's incestuous father and later laid to rest in a cave in the Sicilian countryside.

The Seven Sleepers series by Gilbert Morris takes a modern approach to the story in which seven teenagers must be awakened to fight evil in a post-nuclear-apocalypse world.

The Seven Sleepers are mentioned in the song "Les Invisibles" on the 1988 Blue Öyster Cult album Imaginos.