Shabbat

Judaism's traditional position is that the unbroken seventh-day Shabbat originated among the Jewish people, as their first and most sacred institution.

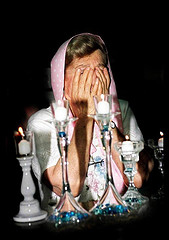

According to halakha (Jewish religious law), Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before the sun sets on Friday evening until the appearance of three stars in the sky on Saturday night, or an hour after sundown.

In many communities, this meal is often eaten in the period after the afternoon prayers (Minchah) are recited and shortly before Shabbat is formally ended with a Havdalah ritual.

A cognate Babylonian Sapattum or Sabattum is reconstructed from the lost fifth Enūma Eliš creation account, which is read as: "[Sa]bbatu shalt thou then encounter, mid[month]ly".

It is regarded as a form of Sumerian sa-bat ("mid-rest"), rendered in Akkadian as um nuh libbi ("day of mid-repose").

[6][7] The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia advanced a theory of Assyriologists like Friedrich Delitzsch[8] (and of Marcello Craveri)[9] that Shabbat originally arose from the lunar cycle in the Babylonian calendar[10][11] containing four weeks ending in a Sabbath, plus one or two additional unreckoned days per month.

Sabbath is commanded and commended many more times in the Torah and Tanakh; double the normal number of animal sacrifices are to be offered on the day.

[32] In modern times, many composers have written sacred music for use during the Kabbalat Shabbat observance, including Robert Strassburg[33] and Samuel Adler.

These include: Havdalah (Hebrew: הַבְדָּלָה, "separation") is a Jewish religious ceremony that marks the symbolic end of Shabbat, and ushers in the new week.

At the conclusion of Shabbat at nightfall, after the appearance of three stars in the sky, the havdalah blessings are recited over a cup of wine, and with the use of fragrant spices and a candle, usually braided.

Jewish law (halakha) prohibits doing any form of melakhah (מְלָאכָה, plural melakhoth) on Shabbat, unless an urgent human or medical need is life-threatening.

The (strict) observance of the Sabbath is often seen as a benchmark for orthodoxy and indeed has legal bearing on the way a Jew is seen by an orthodox religious court regarding their affiliation to Judaism.

Some Orthodox also hire a "Shabbos goy", a non-Jew (who must not be regularly employed by the household in question) to perform prohibited tasks (like operating light switches) on Shabbat.

However, many rabbinical authorities consider the use of such elevators by those who are otherwise capable as a violation of Shabbat, with such workarounds being for the benefit of the frail and handicapped and not being in the spirit of the day.

Others make their keys into a tie bar, part of a belt buckle, or a brooch, because a legitimate article of clothing or jewelry may be worn rather than carried.

[47][48][49][50] If a human life is in danger (pikuach nefesh), then a Jew is not only allowed, but required,[51][52] to violate any halakhic law that stands in the way of saving that person (excluding murder, idolatry, and forbidden sexual acts).

The concept of life being in danger is interpreted broadly: for example, it is mandated that one violate Shabbat to bring a woman in active labor to a hospital.

Examples of these include the principle of shinui ("change" or "deviation"): A violation is not regarded as severe if the prohibited act was performed in a way that would be considered abnormal on a weekday.

This legal principle operates bedi'avad (ex post facto) and does not cause a forbidden activity to be permitted barring extenuating circumstances.

Generally, adherents of Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism believe that the individual Jew determines whether to follow Shabbat prohibitions or not.

For example, some Jews might find activities, such as writing or cooking for leisure, to be enjoyable enhancements to Shabbat and its holiness, and therefore may encourage such practices.

[54] The radical Reform rabbi Samuel Holdheim advocated moving Sabbath to Sunday for many no longer observed it, a step taken by dozens of congregations in the United States in late 19th century.

The Talmud, especially in tractate Shabbat, defines rituals and activities to both "remember" and "keep" the Sabbath and to sanctify it at home and in the synagogue.

In addition to refraining from creative work, the sanctification of the day through blessings over wine, the preparation of special Sabbath meals, and engaging in prayer and Torah study were required as an active part of Shabbat observance to promote intellectual activity and spiritual regeneration on the day of rest from physical creation.

Biblical text to support using the moon, a light in the heavens, to determine days include Genesis 1:14, Psalm 104:19, and Sirach 43:6–8 See references: [63][64][65] Rabbinic Jewish tradition and practice does not hold of this, holding the sabbath to be based on the days of creation, and hence a wholly separate cycle from the monthly cycle, which does not occur automatically and must be rededicated each month.