Shakespeare's handwriting

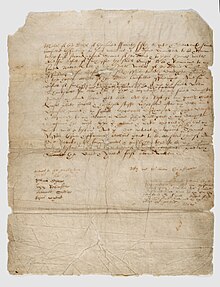

It is believed by many scholars that three pages of the handwritten manuscript of the play Sir Thomas More are also in William Shakespeare's handwriting.

The secretary hand was popular with authors of Shakespeare's time, including Christopher Marlowe and Francis Bacon.

[7] John Heminges and Henry Condell, who edited the First Folio in 1623, wrote that Shakespeare's "mind and hand went together, and what he thought he uttered with that easiness that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers."

In his posthumously published essay, Timber: Or, Discoveries, Ben Jonson wrote:I remember the players have often mentioned it as an honor to Shakespeare, that in his writing, whatsoever he penned, he never blotted out a line.

I had not told posterity this but for their ignorance, who chose that circumstance to commend their friend by wherein he most faulted; and to justify mine own candor, for I loved the man, and do honor his memory on this side idolatry as much as any.

He was, indeed, honest, and of an open and free nature; had an excellent fancy, brave notions, and gentle expressions, wherein he flowed with that facility that sometime it was necessary he should be stopped.

[8][9]The three-page addition to Sir Thomas More, which is attributed by some to Shakespeare, is written in a fluid manner by a skillful and experienced writer.

Throughout, the writing shows a disposition to play with the pen, to exaggerate certain curves, to use heavier downstrokes, and to finish some final letters with a small flourish.

By the late nineteenth century paleographers began to make detailed study of the evidence in the hope of identifying Shakespeare's handwriting in other surviving documents.

[14] The signatures on the Blackfriars document may have been abbreviated because they had to be squeezed into the small space provided by the seal-tag, which they were legally authenticating.

The paleographer Edward Maunde Thompson later criticised the Steevens transcriptions, arguing that his original drawings were inaccurate.

[16] The two signatures relating to the house sale were identified in 1768 and acquired by David Garrick, who presented them to Steevens' colleague Edmond Malone.

[20] Under the circumstances, with evidence limited to those five signatures, an attempt to reconstitute the handwriting that Shakespeare actually used might have been considered impossible.

Thompson identified distinctive characteristics in Shakespeare's hand, which include delicate introductory upstrokes of the pen, the use of the Italian long "s" in the middle of his surname in his signatures, an unusual form of the letter "k", and a number of other personal variations.

[21][22] The first time it was suggested that the three-page addition to the play Sir Thomas More was composed and also written out by William Shakespeare was in a correspondence to the publication Notes and Queries in July 1871 by Richard Simpson, who was not an expert in handwriting.

[24] After more than a year James Spedding wrote to the same publication in support of that particular suggestion by Simpson, saying that the handwriting found in Sir Thomas More "agrees with [Shakespeare's] signature, which is a simple one, and written in the ordinary character of the time.

"[25] After a detailed study of the More script, which included analysing every letter formation, and then comparing it to the signatures, Thompson concluded that "sufficient close resemblances have been detected to bring the two handwritings together and to identify them as coming from one and the same hand," and that "in this addition to the play of Sir Thomas More we have indeed the handwriting of William Shakespeare.

"[26][27] Thompson believed that the first two pages of the script were written quickly, using writing techniques that indicate Shakespeare had received "a more thorough training as a scribe than had been thought probable".

[29] In the late 1930s a possible seventh Shakespeare signature was found in the Folger Library copy of William Lambarde's Archaionomia (1568), a collection of Anglo-Saxon laws.

"[39] In 1985 manuscript expert Charles Hamilton compared the signatures, the handwritten additions to the play Sir Thomas More, and the body of the last will and testament.

In his book In Search of Shakespeare he placed letters from each document side-by-side to demonstrate the similarities and his reasons for considering that they were written by the same hand.

(Sonnet 13, line 9)[43][44][45][46][47][48] On 4 December 1612 Shakespeare's friends, Elizabeth and Adrian Quiney, sold a house to a man named William Mountford for 131 pounds.

[49][50][51] On 20 October 1596 a rough draft was drawn up for an application to the College of Heralds for Shakespeare's father to be granted a coat-of-arms.

The coat-of-arms is seen to be pictorially expressing Shakespeare's name with the verb "shake" shown by the falcon with its fluttering wings grasping a "spear".

For example, scholar Eric Sams, assuming that the pages by Hand D in the play Sir Thomas More are indeed Shakespeare's, points out that Hand D shows what scholar Alfred W. Pollard refers to as "excessive carelessness" in minim errors—that is, writing the wrong number of downstrokes in the letters i, m, n, and u.

[61] This particular characteristic is indicated in numerous misreadings by the original compositor who set the printed type for Edward III.

[60] In London in the 1790s, author Samuel Ireland announced a great discovery of Shakespearean manuscripts, including four plays.

[64] On a loose fly-leaf of a copy of John Florio's translation of the works of Montaigne, is a signature that reads "Willm.

The book was auctioned for a large amount (100 pounds) in 1838 to a London bookseller named Pickering, who then sold it to the British Museum.