Shangani Patrol

Scouting ahead of Major Patrick Forbes's column attempting the capture of the Matabele King Lobengula (following his flight from his capital Bulawayo a month before), it crossed the Shangani late on 3 December 1893.

The patrol's members, particularly Wilson and Captain Henry Borrow, were elevated in death to the status of national heroes, representing endeavour in the face of insurmountable odds.

Controversy surrounds the breakout before the last stand—which various historians have posited might have actually been desertion—and a box of gold sovereigns, which a Matabele inDuna (leader) later said had been given to two unidentified men from Forbes's rear guard on 2 December, along with a message that Lobengula admitted defeat and wanted the column to stop pursuing him.

Amid the Scramble for Africa during the 1880s, the South African-based businessman and politician Cecil Rhodes envisioned the annexation to the British Empire of a swathe of territory connecting the Cape of Good Hope and Cairo—respectively at the southern and northern tips of Africa—and the concurrent construction of a line of rail linking the two.

[n 2] In return for these rights, the company would govern and develop any territory it acquired, while respecting laws enacted by extant African rulers, and upholding free trade within its borders.

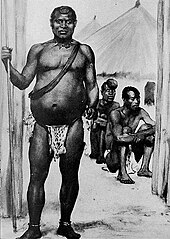

[16] Lobengula's troops were well-drilled and formidable by pre-colonial African standards, but the company's Maxim guns, which had never before been used in battle, far exceeded expectations, according to an eyewitness "mow[ing] them down literally like grass".

[18] Jameson, who now based himself in Bulawayo, wrote the following letter to the Matabele king on 7 November 1893, in English, Dutch and Zulu:[20] I send this message in order, if possible, to prevent the necessity of any further killing of your people or burning of their kraals.

Should you not then arrive I shall at once send out troops to follow you, as I am determined as soon as possible to put the country in a condition where whites and blacks can live in peace and friendliness.This letter, carried by John Grootboom, a coloured man from the Cape, reached Lobengula near Shiloh Mission, about 30 miles (48 km) north of Bulawayo.

Wishing to know whether the king had crossed here or at another point on the river,[23] Forbes sent Major Allan Wilson across to scout ahead with 12 men and eight officers, and told him to return by nightfall.

[29] On returning to his bush camp, Wilson sent a further message to the laager, which reached its destination at around 23:00:[24][27] Napier, Scout Bain and Trooper Robertson were the men acting as runners.

[30] Forbes thought it unwise to attempt a full river crossing at night, which he reasoned might lead to his force being surrounded in the darkness and massacred, but also felt he could not recall Wilson, as to do so would be to lose Lobengula for sure.

[37] The ambushers' shots were initially wild and inaccurate, but they soon began to focus their fire on the exposed Maxim guns and horses, forcing the troopers to retreat to cover.

[39] In an act of desperation, he instead sent three of his men—American scouts Frederick Russell Burnham and Pearl "Pete" Ingram, and Australian Trooper William Gooding—to charge through the Matabele line, cross the river and bring reinforcements back to help, while he, Borrow and the rest made a last stand.

On reaching the main column shaken and out of breath, Burnham leapt from his horse and ran to Forbes: "I think I may say that we are the sole survivors of that party," he quietly confided, before loading his rifle and joining the skirmish.

[39] They used their dead horses for cover, and killed more than ten times their own number (about 500, Mjaan estimated),[4] but were steadily whittled down as the overwhelming Matabele force closed in from all sides.

[4] Late in the afternoon, after hours of fighting, Wilson's men ran out of ammunition, and reacted to this by rising to their feet, shaking each other's hands and singing a song, possibly "God Save the Queen".

[4] At Mjaan's orders, the bodies of the patrol were left untouched,[4] though the whites' clothes and two of their facial skins were collected the next morning to serve as proof to Lobengula of the battle's outcome.

[3] After the battle on the southern side of the Shangani was over, Forbes and his column conducted a cursory search for survivors from Wilson's party, but, unable to cross the river, could see nothing to tell them what had happened.

[49] ... No news from Wilson's party—Forbes in disgrace—Raaff practically running the show ... Matabele raiding parties attacked the retreating column six times during its two-week journey back to Bulawayo.

[4] They also told the trader what had happened to the Shangani Patrol, and led him to the battle site to survey it, as well as to examine and identify the largely skeletonised bodies of the soldiers, which still lay where they had fallen.

[56] Newspapers supportive of British imperialism devoted significant amounts of coverage to the battle, and others which were generally more lukewarm about colonial projects also pursued accounts of the patrol.

The show tells the story of a young colonial army officer in South Africa and Rhodesia, culminating in the third act with a fictionalised account of the First Matabele War.

[61] In historical terms, the Shangani Patrol subsequently became an integral part of Rhodesian identity, with Wilson and Borrow in particular woven into the national tapestry as heroic figures symbolising duty in the face of insuperable odds.

[68] The prosecutor proposed that Sehuloholu could be exaggerating the standard of Sindebele spoken by the men he had met, pointing out that most of the phrases quoted were actually relatively basic, and did not imply a profound understanding of the language.

[68] The version of events recorded by history is based on the accounts of Burnham, Ingram and Gooding, the Matabele present at the battle (particularly inDuna Mjaan), and the men of Forbes's column.

[75] First-hand Matabele accounts such as Mjaan's, which were first recorded during 1894, appear to confirm the character of the break-out, saying that three of the white men they were fighting—including Burnham, whom several of them recognised—left during a lull in the battle, just after Wilson withdrew to his final position.

[4][76] While all of the direct evidence given by eyewitnesses supports the findings of the Court of Inquiry, some historians and writers debate whether or not Burnham, Ingram and Gooding really were sent back by Wilson to fetch help, and suggest that they might have simply deserted when the battle got rough.

[76] J P Lott, another historian, comments that Wilson had sent runners to Forbes twice the previous night, when he was already at very close quarters with the Matabele and with far fewer men; he surmises that it would not be out of the ordinary for the major to do so again.

[83] A short war film based the show's version of the final engagement, Major Wilson's Last Stand, was released by Levi, Jones & Company studios in 1899.

[86] Though much of the mythology surrounding the patrol and the site has dissipated in the national consciousness since the country's reconstitution as Zimbabwe in 1980, World's View endures as a tourist attraction to this day.