Sharaku

His active career as a woodblock artist spanned ten months; his prolific work met disapproval and his output came to an end as suddenly and mysteriously as it had begun.

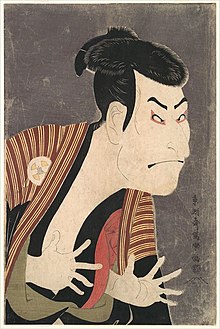

His compositions emphasize poses of dynamism and energy, and display a realism unusual for prints of the time—contemporaries such as Utamaro represented their subjects with an idealized beauty, while Sharaku did not shy from showing unflattering details.

His mastery of the medium with no apparent apprenticeship has drawn much speculation, and researchers have long tried to discover his true identity—amongst the dozens of proposals, some suggest he was an obscure poet, others a Noh actor, or even the ukiyo-e master Hokusai.

[5] He and other members of the Katsukawa school popularized ōkubi yakusha-e actor prints and the dusting of mica in the backgrounds to produce a luxurious glittering effect.

Some of the policies restricted extravagant fashions, and Kabuki theatres faced strict control over their perceived excesses and limits on actors' incomes.

Late Edo-period art nevertheless flourished, and new works and popular actors continued to rapidly appear in kabuki theatre, where realistic performances came in vogue.

[10] Over 140 prints have been established as the work of Sharaku; the majority are portraits of actors or scenes from kabuki theatre, and most of the rest are of sumo wrestlers or warriors.

[12] They depict actors from kabuki plays performed at three theatres: Hana-ayame Bunroku Soga at the Miyako-za; Katakiuchi Noriyaibanashi and the jōruri Hana-shōbu Omoi no Kanzashi at the Kiri-za; and the kiri-kyōgen Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura at the Kawarazaki-za.

[15] Of the 8 ōban prints, 7 are full-length portraits of pairs of actors;[16] the other is of the announcer at Miyako-za—the only full-body yakusha-e of a single subject in Sharaku's œuvre.

The only one of these ōban prints to employ black mica is that of Ichikawa Komazō III as Kameya Chūbei and Nakayama Tomisaburō as Umegawa from Tsuki no Mayu Koi no Monaka.

[12] From the eleventh[g] month of Kansei 6, 18 of the prints come from Oshukubai Koi no Hatsune at the Miyako-za; 21 from Otokoyama Oedo no Ishizue and the jōruri Shinobu Koi Suzume no Irodoki at the Kiri-za; 15 from Matsuhamisa Onna Kusunoki and the jōruri Kagurazuki Iwai no Iroginu at the Kawarazaki-za; 4 are of sumo wrestlers, one of which is a triptych; and two are a memorial to Ichikawa Monnosuke II [ja].

Sharaku focuses on transitional poses as before, but the busier designs weaken the effect by drawing attention away from the actors' expressions to other elements of the composition.

[23] Nonetheless, from the first Sharaku's prints appeared amongst the technical vanguard, with unusually realistic portrayals of their subjects and using extravagant techniques such as the dusting of mica in the backgrounds.

Hillier compares Sharaku to French painter Paul Cézanne, who he believes "has to struggle to express himself, hampered and angered by the limitations of his draughtsmanship".

[28] A book on haiku theory and aesthetics from 1776 includes two poems attributed to a Sharaku, and references to a Nara poet by the same name appear in a 1776 manuscript and a 1794 poetry collection.

Amongst these documents are those that suggest Sharaku died between 1804 and 1807, including a Meiji-era manuscript that specifies the seventeenth day of the fifth month of 1806, and that his grave was marked in Kaizenji Temple in Asakusa in Edo.

[35] Hokusai changed his art name dozens of times throughout his long career—government censorship under the Kansei Reforms[m] may have motivated him to choose a name to distance his actor portraits from his other work.

[42] The subject of an Eishōsai Chōki portrait of Takashimaya O-Hisa holds a hand fan decorated with Sharaku's Kōshirō Matsumoto IV as Sakanaya Gorobee.

[18] On a decorated kite illustrated in Jippensha Ikku's book Shotōzan Tenarai Hōjō (1796) appears Sharaku's depiction of kabuki actor Ichikawa Ebizō IV; the accompanying text is filled with puns, jargon, and double entendres that have invited interpretation as commentary on the decline of Sharaku's later works and events surrounding his departure from the ukiyo-e world,[43] including speculation that he had been arrested and imprisoned.

"[n]The Ukiyo-e Ruikō was not a published book, but a manuscript that was hand-copied over generations, with great variations in content, some of which has fueled speculation as to Sharaku's identity.

[49] In his Chats on Japanese Prints of 1915 Arthur Davison Ficke declared, "Sharaku stands on the highest level of genius, in a greatness unique, sublime, and appalling.

[52] As they are in collections scattered throughout the world general research on Sharaku's works has followed different threads in Japan and the West has proved time-consuming.

He found Sharaku "repudiated normalcy"[59] and departed from strict realism and anatomical proportions to achieve expressive, emotional effects.