Shell growth in estuaries

Changing conditions in estuaries and coastal regions are especially relevant to human interests, because about 50% of global calcification and 90% of fish catch occurs in these locations.

There are several variations in calcium carbonate (CaCO3) skeletons, including the two different crystalline forms, calcite and aragonite, as well as other elements which can become incorporated into the mineral matrix, altering its properties.

Acidity (pH) and carbonate saturation states also reach extremes in estuarine systems, making these habitats a natural testing ground for the impacts of chemical changes on the calcification of shelled organisms.

[23] Since saturation state can be affected by both solubility and carbonate ion concentrations, it can be strongly impacted by environmental factors such as temperature and salinity.

Water temperatures vary widely on a seasonal basis in polar and temperate habitats, inducing metabolic changes in organisms exposed to these conditions.

Comeau et al.[4][26] point out that cold locations such as the Arctic show the most dramatic decreases in aragonite saturation state (Ω) associated with climate change.

[15] In addition to impacting the solubility and saturation state of calcite and aragonite, temperature can alter the composition of shell or calcified skeletons, especially influencing the incorporation of magnesium (Mg) into the mineral matrix.

[6] Magnesium content of carbonate skeletons (as MgCO3) increases with temperature, explaining a third of the variation in sea star Mg:Ca ratios.

[6] As a result of the positive correlation between temperature and Mg content, organisms that live in colder environments such as the deep sea and high latitudes have a lower percentage of MgCO3 incorporated into their shells.

[18] This response is not limited to animals or open ocean species, since crustose coralline algae also increase their incorporation of magnesium and therefore their solubility at elevated temperatures.

The impact that these temperature-induced chemical changes have on shell deposition has been repeatedly demonstrated for a wide array of organisms that inhabit estuarine and coastal systems, highlighting the cumulative effect of all temperature-influenced factors.

[27] Eastern oysters and crustose coralline algae have also been shown to increase their calcification rates with elevated temperature, though this can have varied effects on the morphology of the organism.

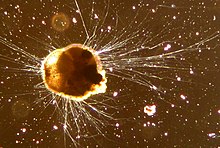

[29] The predatory intertidal snail Nucella lapillus also develops thicker shells in warmer climates, likely due to constraints on calcification in cold water.

In oceanography and marine biology, it has been traditional to express salinity not as a percent, but as permille (parts per thousand) (‰), which is approximately grams of salt per kilogram of solution.

Even organisms in the same location experience broad swings in salinity with the tides, exposing them to very different water masses with chemical properties that provide varying levels of support for calcification processes.

Salinity displays a positive correlation with magnesium:calcium (Mg:Ca) ratios, though shows only about half as much influence as temperature.

The slopes of these lines are the same, with only the intercept changing for the different carbonate species, highlighting that at standard temperature and pressure, aragonite is more soluble than calcite.

[35] Both alkalinity, or acid buffering capacity, and CaCO3 saturation state increase with salinity, which may help estuarine organisms to overcome fluctuations in pH that could otherwise negatively impact shell formation.

[17] Therefore, even though higher salinity can cause increased saturation states of calcite and aragonite, there are many other factors that interact in this system to influence the shell deposition of estuarine organisms.

[18] Higher alkalinity in marine waters is especially important since carbon dioxide produced via respiration in estuaries can lower pH, which decreases saturation states of calcite and aragonite and can cause CaCO3 dissolution.

Increases in salinity and temperature can counteract the negative impact of pH on calcification rates, as they elevate calcite and aragonite saturation states and generally facilitate more favorable conditions for shell growth.

Shell growth and calcification rate are the cumulative outcome of the impacts of temperature and salinity on water chemistry and organismal processes such as metabolism and respiration.

It has been established that temperature and salinity influence the balance of the carbonate equilibrium, the solubility and saturation state of calcite and aragonite, as well as the amount of magnesium that gets incorporated into the mineral matrix of the shell.

In 1998, the average global aragonite saturation state was 390%, a range commonly experienced since the last glacial period and a percentage above which calcification rates plateaued.

The interaction between pH, temperature and salinity in estuaries and in the world ocean will drive calcification rates and determine future species assemblages based on susceptibility to this change.