Shopi

[3] The boundaries that are most commonly used overlap with the Bulgarian folklore and ethnographic regions and incorporate Central Western Bulgaria and the Bulgarian-populated areas in Serbia.

[8] According to some Shopluk studies dating back to the early 20th century, the name "Shopi" comes from the staff that local people, mostly pastoralists, used as their main tool.

In Bulgaria, the Shopi started gaining visibility as a "group" in the course of the 19th-century waves of migration of poor workers from the Shopluk villages to Sofia.

[15][16] According to the Czech Slavist Konstantin Jireček, the Shopi differed a lot from other Bulgarians in language and habits, and were generally regarded as a simple folk.

[19][20] The Oxford historian C. A. Macartney studied the Shopi during the 1920s and reported that they were despised by the other inhabitants of Bulgaria for their stupidity and bestiality, and dreaded for their savagery.

[23] Another German, Wolf Andreas von Steinach, on his way home from Constantinople in 1583, placed the boundary between Bulgarian and Serbs just west of Niš.

[24] The same thing was done in the 1621 journal of yet another traveller, French diplomat Louis Deshayes, Baron de Courmemin, who emphasised that the boundary had been shown to him "by locals".

[25] In the 1590s, Austrian apothecary Hans Seidel wrote about hundreds of chopped-off heads of Bulgarian villagers rolling along the road from Sofia to Niš.

[26] In 1664, Englishman John Burberry was baffled by several Bulgarian women in Bela Palanka who threw pieces of butter with salt in front of his company (probably wishing them a safe journey).

[28] A decade or so later, Italian military specialist in Austrian service Luigi Ferdinando Marsili described Dragoman, Kalotina and Dimitrovgrad as "Bulgarian villages".

[29] Other travellers who put the ethnographic boundary between Serbs and Bulgarians at Niš include German George Christoff Von Neitzschitz, in 1631;[30] Austrian diplomat Paul Taffner, as part of an embassy to the Sublime Porte, in 1665;[31] German diplomat Gerard Cornelius Von Don Driesch, sent on a mission to Constantinople on the orders of Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1723;[32] Armenian geographer Hugas Injejian in 1789, etc.

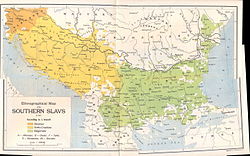

A total of eleven primary ethnic maps of the Balkans were produced between 1842 and 1877: by Slovak philologist Pavel Jozef Šafárik in 1842, Ami Boué in 1847, French ethnographer Guillaume Lejean in 1861, English travel writers Georgina Muir Mackenzie and Paulina Irby in 1867, Russian ethnographer Mikhail Mirkovich in 1867, Czech folklorist Karel Jaromír Erben in 1868, German cartographer August Heinrich Petermann in 1869, renowned German geographer Heinrich Kiepert in 1876, British mapmaker Edward Stanford, French railway engineer Bianconi and Austrian diplomat Karl Sax, all three in 1877.

With the exception of Bianconi and Stanford's maps that portrayed all of Thrace, Macedonia and southern Albania as ethnically Greek and are generally described as having a pro-Greek bias, all other nine maps establish the Serbo-Bulgarian ethnic boundary along the Timok, then just north of Niš and finally along the Šar Mountains, thus defining the entire Shopluk as Bulgarian.

[40] Of interest is also the retroactive study of Bulgaria's population in the 1860s by Russian philologist and dialectologist Afanasiy Selischev, which concluded that the valleys extending from Niš through Pirot and Sofia to the Gate of Trajan near Ihtiman, i.e., the central Shopluk featured the largest concentration of Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire.

[49] The Načertanije envisaged a "Piedmont"-like role for Serbia on the Balkans and the restoration of the medieval Serbian Empire by indoctrinating all surrounding Slavic peoples with pro-Serbian national ideology.

In 1867, Serbia launched a massive campaign to open Serbian schools across the Shopluk and Macedonia, with a special focus on Torlak-speaking areas.

[52] Serbia's main competitive advantage was that it offered subsidized teacher salaries, while the Exarchate financed its schools with the membership dues of its parishioners.

[55] In this connection, Felix Kanitz noted that back in 1872 the inhabitants of the city would have never imagined that they would be free of the Turks so soon only to end up under foreign rule again.

[67] Isoglosses are based on 19th and early 20th century records rather than on current data, and Transdanubian settler dialects in Banat and Bessarabia are therefore excluded.

With the establishment of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and the codification of a separate Macedonian language in the 1940s, the bipartite division of the Shopluk has become tripartite.

[68] Most of the area traditionally inhabited by the Shopi is within Bulgaria, while the western borderlines are split between Serbia and the Republic of North Macedonia.

This is particularly true for northwestern Bulgaria, but even in areas close to Sofia, the local population identifies in different ways, e.g., as граовци (graovci) around Pernik and Breznik, знеполци (znepolci) around Tran, торлаци (Torlaks) on the northern and southern side of the Balkan mountain, etc.

Some Shope women wear a special kind of sukman called a litak, which is black, generally is worn without an apron, and is heavily decorated around the neck and bottom of the skirt in gold, often with great quantities of gold-colored sequins.

A distinguished writer from the region is Elin Pelin who actually wrote some comic short stories and poems in the dialect, and also portrayed life in the Shopluk in much of his literary work.