Fragmentation (weaponry)

The resulting high-velocity fragments produced by either method are the main lethal mechanisms of these weapons, rather than the heat or overpressure caused by detonation, although offensive grenades are often constructed without a frag matrix.

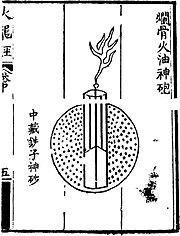

[5] For this bomb you take tung oil, yin hsiu, salammoniac, chin chih, scallion juice, and heat them so as to coat a lot of iron pellets and bits of broken porcelain.

When the projectile is fired, it travels a pre-set distance along a ballistic trajectory, then the fuse ignites a relatively weak secondary charge (often black powder or cordite) in the base of the shell.

[8] The use of high explosives with a fragmenting case improves efficiency as well as propelling a larger number of fragments at a higher velocity over a much wider area (40 to 60 times the diameter of the shell), giving high-explosive shells a vastly superior battlefield lethality that was largely impossible before the Industrial Era.

World War I was the first major conflict in which HE shells were the dominant form of artillery; the failure to adapt infantry tactics to the massive increase in lethality they produced was a major element in producing the ghastly subterranean stalemate conditions of trench warfare, in which neither side could risk movement above ground without the guarantee of instant casualties from the constant, indiscriminate hail of HE shell fragments.

shrapnel shell