Shrapnel shell

The munition has been obsolete since the end of World War I for anti-personnel use; high-explosive shells superseded it for that role.

At the time, artillery could use "canister shot" to defend themselves from infantry or cavalry attack, which involved loading a tin or canvas container filled with small iron or lead balls instead of the usual cannonball.

When fired, the container burst open during passage through the bore or at the muzzle, giving the effect of an oversized shotgun shell.

At longer ranges, solid shot or the common shell—a hollow cast-iron sphere filled with black powder—was used, although with more of a concussive than a fragmentation effect, as the pieces of the shell were very large and sparse in number.

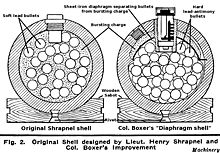

His shell was a hollow cast-iron sphere filled with a mixture of balls (“shot”) and powder, with a crude time fuze.

If the fuze was set correctly then the shell would break open, either in front of or above the intended human objective, releasing its contents (of musket balls).

However, in 1852, Colonel Boxer proposed using a diaphragm to separate the bullets from the bursting charge, which proved successful and was adopted the following year.

The design was improved by Captain E. M. Boxer of the Royal Arsenal around 1852 and crossed over when cylindrical shells for rifled guns were introduced.

It also withstood the force of the powder charge without shattering so that the bullets were fired forward out of the shell case with increased velocity, much like a shotgun.

[5] The modern thin-walled forged-steel design made feasible shrapnel shells for howitzers, which had a much lower velocity than field guns, by using a larger gunpowder charge to accelerate the bullets forward on bursting.

[7] The ideal shrapnel design would have had a timer fuse in the shell base to avoid the need for a central tube, but that was not technically feasible because of the need for manually adjust the fuse before firing and was in any case rejected from an early date by the British because of risk of premature ignition and irregular action.

[10] The important points to note about shrapnel shells and bullets in their final stage of development in World War I are:

Shorter ranges meant the flat trajectories might not clear the firers' own parapets, and fuses could not be set for less than 1,000 yards.

Furthermore, they needed good platforms with trail and wheels anchored with sandbags, and an observing officer had to monitor the effects on the wire continuously and make any necessary adjustments to range and fuse settings.

3 Artillery in Offensive Operations", issued in February 1917 with added detail including the amount of ammunition required per yard of wire frontage.

Shrapnel provided a useful "screening" effect from the smoke of the black-powder bursting charges when the British used it in "creeping barrages".

One of the key factors that contributed to the heavy casualties sustained by the British at the Battle of the Somme was the perceived belief that shrapnel would be effective at cutting the barbed wire entanglements in no man's land (although it has been suggested that the reason for the use of shrapnel as a wire-cutter at the Somme was because Britain lacked the capacity to manufacture enough HE shell[13]).

As a result, shrapnel was later only effective in killing enemy personnel; even if the conditions were correct, with the angle of descent being flat to maximise the number of bullets going through the entanglements, the probability of a shrapnel ball hitting a thin line of barbed wire and successfully cutting it was extremely low.

The bullets also had limited destructive effect and were stopped by sandbags, so troops behind protection or in bunkers were generally safe.

When a timed fuse was set the shell functioned as a shrapnel round, ejecting the balls and igniting (not detonating) the TNT, giving a visible puff of black smoke.

When allowed to impact, the TNT filling would detonate, becoming a high-explosive shell with a very large amount of low-velocity fragmentation and a milder blast.

[17] It appears to be similar to the German design, with bullets embedded in TNT rather than resin, together with a quantity of explosive in the shell nose.

A new British streamlined shrapnel shell, Mk 3D, had been developed for BL 60 pounder gun in the early 1930s, containing 760 bullets.

The shell consisted of approximately 8,000 one-half-gram flechettes arranged in five tiers, a time fuse, body-shearing detonators, a central flash tube, a smokeless propellant charge with a dye marker contained in the base and a tracer element.

The round was complex to make, but is a highly effective anti-personnel weapon – soldiers reported that after beehive rounds were fired during an overrun attack, many enemy dead had their hands nailed to the wooden stocks of their rifles, and these dead could be dragged to mass graves by the rifle.

It is said that the name beehive was given to the munition type due to the noise of the flechettes moving through the air resembling that of a swarm of bees.

By using rod-like sub-projectiles, a much greater thickness of material can be penetrated, greatly increasing the potential for disruption of the incoming RV.

1 Gunpowder bursting charge

2 Bullets

3 Time fuze

4 Ignition tube

5 Resin holding bullets in position

6 Steel shell wall

7 Cartridge case

8 Shell propellant

The spherical bullets are visible in the sectioned shell (top left), and the cordite propellant in the brass cartridge is simulated by a bundle of cut string (top right). The nose fuse is not present in the sectioned round at top but is present in the complete round below. The tube through the centre of the shell is visible, which conveyed the ignition flash from the fuse to the small gunpowder charge in the cavity visible here in the base of the shell. This gunpowder charge then exploded and propelled the bullets out of the shell body through the nose.