Sickness behavior

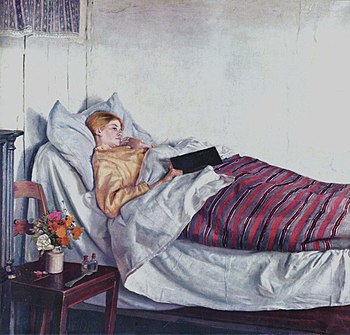

Such illness responses include lethargy, depression, anxiety, malaise, loss of appetite,[3][4] sleepiness,[5] hyperalgesia,[6] reduction in grooming[1][7] and failure to concentrate.

Initially it was thought that this was due to physical weakness that resulted from diverting energy to the body processes needed to fight infection.

[11][12] In 1987, Benjamin L. Hart brought together a variety of research findings that argued for them being survival adaptations that if prevented would disadvantage an animal's ability to fight infection.

In the 1980s, the blood-borne factor was shown to be proinflammatory cytokines produced by activated leukocytes in the immune system in response to lipopolysaccharides (a cell wall component of Gram-negative bacteria).

[14] Sickness behavior in its different aspects causes an animal to limit its movement; the metabolic energy not expended in activity is diverted to the fever responses, which involves raising body temperature.

[20] Peripheral cytokines are capable of entering the brain directly[21][22] but are large lipophilic polypeptide proteins that generally do not easily passively diffuse across the blood-brain barrier.

[31] The mood effects caused by interleukin-6 following an immune response have been linked to increased activity within the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex,[32] an area involved in the etiology of depression.

[33] Inflammation-associated mood change can also produce a reduction in the functional connectivity of this part of the brain to the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and superior temporal sulcus.