Battle of Alesia

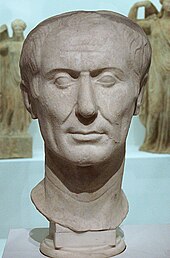

It was fought by the Roman army of Julius Caesar against a confederation of Gallic tribes united under the leadership of Vercingetorix of the Arverni.

The Battle of Alesia marked the end of Gallic independence in the modern day territory of France and Belgium.

[10] The event is described by Caesar himself in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico as well as several later ancient authors (namely Plutarch and Cassius Dio).

While he went to Gallia Cisalpina to collect three other legions, the Helvetii attacked the territories of the Aedui, Ambarri, and Allobroges, three Gallic tribes, which called for Caesar's help.

This was a subject of immense concern for the Gauls, who feared the Romans would destroy the Gallic holy land, which the Carnutes watched over.

Over the winter the charismatic king of the Arverni tribe, Vercingetorix, assembled an unprecedented grand coalition of Gauls.

He rushed north in attempt to prevent the revolt from spreading, heading first to Provence to see to its defense, and then to Agedincum to counter the Gallic forces.

Vercingetorix abandoned a great many oppidum, seeking to only defend the strongest, and to ensure the others and their supplies could not fall into Roman hands.

Once again, Caesar's hand was forced by a lack of supplies, and he besieged the oppidum of Avaricum where Vercingetorix had pulled back to.

Eventually, the artillery broke a hole in the wall, and the Gauls were unable to stop the Romans from taking the settlement.

Caesar (whose self-reported casualty numbers are likely much lower than the actual amount) claims that 700 men died including 46 centurions.

The two armies met in the Battle of the Vingeanne, where Caesar won the subsequent victory defeating Vercingetorix's cavalry.

Vercingetorix was fine with this, as he intended to use Alesia as a trap to conduct a pincer attack on the Romans, and sent a call for a relieving army at once.

Archeological evidence suggests the lines were not continuous as Caesar claims, and made much use of the local terrain, but it is apparent that they worked.

Caesar placed the legions in front of the camp in case of a sortie by the enemy infantry and got his Germanic allies to pursue the Gallic cavalry.

[16] Before the encompassing fortifications were complete and under cover of night, Vercingetorix sent out all his cavalry to rally the tribes to war and come to aid him at Alesia.

In front of these, one pes (0.3 m, 0.97 ft) stakes with iron hooks were sunk into the ground and scattered close to each other all over the field.

The inhabitants of the town also sent out their wives and children to save food for the fighters, hoping that Caesar would take them as captives and feed them.

The north side of a hill could not be included in the Roman works and they placed a camp with two legions on steep and disadvantageous ground (this is indicated by a circle in the figure).

They fled their camps and Caesar commented that "had not the soldiers been wearied by sending frequent reinforcements, and the labour of the entire day, all the enemy's forces could have been destroyed".

[28] With the revolt crushed, Caesar set his legions to winter across the lands of the defeated tribes to prevent further rebellion.

The Senate declared 20 days of thanksgiving for this victory but, due to political reasons, refused Caesar the honour of celebrating a triumphal parade, the peak of any general's career.

Vercingetorix was taken prisoner and held as a captive in Rome for the next five years awaiting Caesar's triumph (which was delayed by the Civil War).

The legions in Gaul were eventually pulled out in 50 BC as the civil war drew near, for Caesar would need them to defeat his enemies in Rome.

Gaul would not formally be made into Roman provinces until the reign of Augustus in 27 BC, and there may have been unrest in the region as late as AD 70.

[31] Paul K. Davis writes that "Caesar's victory over the combined Gallic forces established Roman dominance in Gaul for the next 500 years.

In the 1960s, a French archaeologist, André Berthier, argued that the hill top was too low to have required a siege, and that the "rivers" were actually small streams.

[33] Berthier proposed that the location of the battle was at Chaux-des-Crotenay at the gate of the Jura mountains – a place that better suits the descriptions in Caesar's Gallic Wars.

Classical historian and archaeologist Colin Wells took the view that the excavations at Alise-Sainte-Reine in the 1990s should have removed all possible doubt about the site and regarded some of the advocacy of alternative locations as "...passionate nonsense".

Caesar, in his De Bello Gallico, refers to a Gallic relief force of a quarter of a million, probably an exaggeration to enhance his victory.