Siege of Khartoum

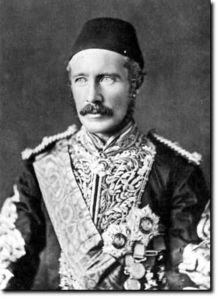

The British refused to send a military force to the area, instead appointing Charles George Gordon as Governor-General of Sudan, with orders to evacuate Khartoum and the other garrisons.

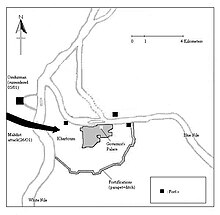

Rather than evacuating immediately, Gordon began to fortify the city, which was cut off when the local tribes switched their support to the Mahdi.

Approximately 7,000 Egyptian troops and 27,000 (mostly Sudanese) civilians were besieged in Khartoum by 30,000 Mahdist warriors, rising to 50,000 by the end of the siege.

[1] A revolt had begun in Sudan in 1881, when Muhammad Ahmad claimed to be the mahdi – the redeemer of Islam prophesied in the hadith scriptures.

The Mahdi's forces captured the Egyptians' equipment and overran large parts of Sudan, including Darfur and Kordofan.

The British soldier Major-General Charles George Gordon, a former Governor-General of Sudan (1876–1879), was re-appointed to that post, with orders to conduct the evacuation.

The Mahdi claimed dominion over the entire Islamic world, which led Gordon to believe that the revolt would not end with control of Sudan, but would attempt to conquer Egypt and perhaps the wider region.

[5] On his way to Khartoum with his assistant, Colonel John Stewart, Gordon stopped in the town of Berber, Sudan to address an assembly of tribal chiefs.

[6] Gordon arrived at Khartoum on 18 February 1884, finding it was safely occupied by a garrison of 7,000 Egyptian troops and 27,000 civilians.

His first actions were to reverse several policies introduced by the Egyptians since he had last been Governor-General five years earlier: arbitrary imprisonments were cancelled, torture was halted and its instruments were destroyed, and taxes were remitted.

To enlist the support of the population, Gordon re-legalised slavery in Sudan, despite having (unsuccessfully) attempted to abolish it in his previous term.

He declared himself honour-bound to rescue the garrisons and defend the Sudanese in Khartoum; it is unclear whether this was a deliberate attempt to delay the evacuation (or avoid it entirely).

In the southern part of the town, which faced the open desert, he prepared an elaborate system of trenches, makeshift Fougasse-type land mines, and wire entanglements.

By early April 1884, the tribes north of Khartoum had risen in support of the Mahdi, including those Gordon had met at Berber.

A separate attempt to send a steamboat along the Nile to Cairo also failed; all the passengers were killed, including Colonel Stewart.

The details of the final assault are unclear, but hearsay accounts[citation needed] were that by 3:30 am, the Mahdists had outflanked the city wall where it met the Nile.

Meanwhile, another force, led by Al Nujumi, broke down the Massalamieh Gate, despite taking casualties from the land mines and barbed wire obstacles laid out by Gordon's men.

[14] In another version, Gordon was recognised by Mahdists while attempting to reach the neutral Austrian consulate in the city, who shot him dead in the street.

According to Orphali, Gordon died fighting on the stairs leading from the first to the ground floor of the west wing of the palace.

Orphali stated that:[16] With his life's blood pouring from his breast [...] he fought his way step by step, kicking from his path the wounded and dead dervishes [...] and as he was passing through the doorway leading into the courtyard, another concealed dervish almost severed his right leg with a single blow.Orphali claimed he was then knocked unconscious, waking unharmed several hours later to find Gordon's decapitated body near to him.

A small part of the relief expedition (28 men led by colonel Charles Wilson, embarked on two of Gordon's steamboats) arrived within sight of Khartoum two days after it fell.

The Mahdi was left in control of the entire country, with the exceptions of the city of Suakin on the Red Sea coast and the Nile town of Wadi Halfa on the Sudan-Egypt border, which were garrisoned by the Anglo-Egyptian force.

In the immediate aftermath of the Mahdist victory, the British press blamed Gordon's death on Gladstone, who was accused of being excessively slow to send relief to Khartoum.

Gladstone had never wanted to get involved in Sudan and felt some sympathy for those Sudanese who sought to end Egyptian colonial rule.

Complex international events led to further European expansion into Africa, compelling the British to take a more active role in the conflict.