Silesian independence

Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526.

According to some, the party supporting the independence of Upper Silesia is the Silesian Autonomy Movement (RAŚ), established in 1990.

In modern history, they have often been pressured to declare themselves to be German, Polish or Czech, and use the language of the nation which was in control of Silesia.

[9] The Silesian People's Party was founded in summer of 1908 by the principal of an elementary school, Józef Kożdoń, in Skoczów.

The goals of the SPP were not new – similar sentiments had been present in Cieszyn Silesia since the Revolutions of 1848[13] – but this was the first time that supporters of Silesian independence were organized into a distinct political party.

Such sentiments were also voiced informally by community institutions, like the paper Nowy Czas (New Time), edited by preacher Theodor Haase.

"The Szlonzakian movement had expanded in the nineties of the 19th century, collecting Slavic people who didn’t want to vote for Poles or Czechs and chose attachment to a separate Silesian nation".

The SPP won in 39 municipalities of the counties of Bielsko and Cieszyn: Jaworze and Jasienica in the judicial district of Bielsko; Bładnice Dolne, Cisownica, Goleszów, Godziszów, Górki Wielkie, Harbutowice, Hermanice, Kozakowice Górne, Kozakowice Dolne, Łączka, Międzyświeć, Nierodzim, Simoradz, Wieszczęta, Wilamowice and Ustroń (here with a coalition of Szlonzakians and Germans) in the judicial district of Skoczów; Bąków, Drogomyśl, Pruchna, Zaborze and Rudzica (here with a coalition of Szlonzakians and Poles) in the judicial district of Strumień; Bażanowice, Dzięgielów, Gumna, Konská, Leszna Górna, Komorní Lhotka, Nebory, Puńców, Svibice, Zamarski, Horní Žukov and Šumbark (here with a coalition of Szlonzakians and Poles) in the judicial district of Cieszyn; Lyžbice, Mosty u Jablunkova and Oldřichovice in the judicial district of Jablunkov.

Even when the SPP officially supported Czechoslovakia, the party did not abandon the option of independence, which was still advocated by its allies, the Germans of Cieszyn Silesia.

[23] In January 1934, Konrad Markiton, Jan Pokrzyk, Paweł Teda, Alfons Pośpiech, Jerzy Jeleń and Waleska Kubistowa re-formed the Silesian People's Party in Katowice.

On 15 April 1934 Polish police confiscated the first issue of the party's bilingual paper, Śląska Straż Ludowa – Schlesische Volkswacht (Silesian People's Watch) and stamped its editorial office.

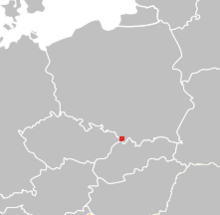

[24] The movement was founded by the Upper Silesian Committee (German: Oberschlesisches Komitee; Polish: Komitet Górnośląski) on 27 November 1918 in Rybnik, Poland by three Catholics: attorney and Wodzisław Śląski Workers Council chairman Ewald Latacz; Thomas Reginek, a priest from Mikulczyce (present-day Zabrze), and educator and Racibórz Workers' and Soldiers' Council chairman Jan Reginek.

The Rybnik Upper Silesian Committee demanded an "independent political stance" from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Germany and guaranteed neutrality similar to that in Switzerland and Belgium.

[25] On 5 December 1918 a German-language brochure, "Oberschlesien – ein Selbständiger Freistaat" ("Upper Silesia – independent/autonomous free state", probably written by Thomas Reginek) was published by the Committee for the Creation of the Upper Silesian Free State in Katowice (German: Komitee zur Vorbereitung eines oberschlesischen Freistaates in Kattowitz).

The rest did not feel any strong connections to either of those nations; according to Wojciech Korfanty's estimations, this last group represented up to a third of the total whole population of the region.

[28] The Treaty of Versailles resolved that a plebiscite be conducted so that the local population could decide whether Upper Silesia should be assigned to Poland or to Germany.

From the point of view of the social and economic development of the Silesian Voivodeship, the autonomy that the region enjoyed in the interwar period is quite generally assessed positively.

The territory returned to Polish possession at the end of the war, and the 1920 act giving autonomous powers to the Silesian Voivodeship was formally repealed by a law of 6 May 1945.

This drastically affected the situation of the population living in Opole Silesia, which remained within the borders of the German state after the First World War.

[32] After the People's Republic of Poland administration took over the region, it was not possible, according to the official position of the authorities, to maintain further coexistence with the large German minority.

As Stanisław Senft noted, "from the very beginning there was a declared desire to de-Germanise the region and remove people not only of foreign, non-Polish nationality, but to erase the traces of the multicultural past of the annexed area".

The effects of this were, among others: the process of nationality verification of Silesians and granting Polish citizenship to those who passed it successfully, the mass displacement of the population, the processes of settlement of the Polish population and the political system transformations, consisting in the change of property relations and the nationalisation of the economy.

The sense of exclusion was further intensified by negative experiences with the immigrant population showing discriminatory attitudes and the stereotype of "Polnische Wirtschaft" (seeing Polish workers as disorganised, inefficient and lazy)[33] cultivated and perpetuated.

[32] The 1980s brought a radical change in attitudes towards Silesia; the discourse on the national identity of Silesians was gradually liberated.

The movement participated in the 1991 Polish parliamentary elections and received 40,061 votes (0.36%) and two seats, one of its MPs was Kazimierz Świtoń.

The results of the survey revealed a predominance of Silesian ethnic identification (over 70%) and clear sympathies towards the autonomy of Upper Silesia (30%–50%).

In 2000 the Polish Office For State Protection warned in its report that RAŚ may be a potential threat to Poland's interests.

The state called the Republic of Poland, of which I'm a citizen, refused to give me and my friends a right to self-determination and so that's why I do not feel obligated to loyalty towards this country.

[39] Ryszard Czarnecki, a Polish politician who is a Member of the European Parliament for the Lower Silesian and Opole constituency from Law and Justice, stated on his official Europarliament site that: "On the one hand it proves how contumely and effrontery are Silesian separatists, on the other Polish media can play a positive role only if they want to oppose such iniquity, such defamation of the fallen Poles [who died] from the German hands during the II World War.

[44] Polish Catholic magazine Gość Niedzielny compared Silesian separatism to Basque nationalism, stating that both nations have a long history of having a separate identity and culture, and concluded that the Silesian separatist movement has a potential to become as strong as the Basque movement.