The Silmarillion

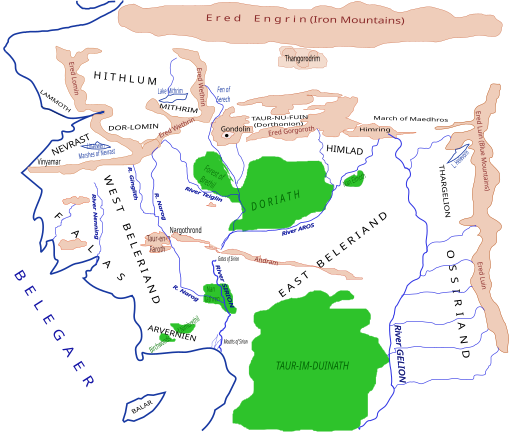

[T 2] It tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the ill-fated region of Beleriand, the island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—are set.

The next section, Quenta Silmarillion, which forms the bulk of the collection, chronicles the history of the events before and during the First Age, including the wars over three jewels, the Silmarils, that gave the book its title.

The book shows the influence of many sources, including the Finnish epic Kalevala, Greek mythology in the lost island of Atlantis (as Númenor) and the Olympian gods (in the shape of the Valar, though these also resemble the Norse Æsir).

In a few cases, this meant that he had to devise completely new material, within the tenor of his father's thought, to resolve gaps and inconsistencies in the narrative,[4] particularly Chapter 22, "Of the Ruin of Doriath".

[T 4] The book covers the history of the world, Arda, up to the Third Age, in its five sections: Ainulindalë (Quenya: "The Music of the Ainur"[T 6]) takes the form of a primary creation narrative.

After he destroyed the two lamps, Illuin and Ormal, that illuminated the world, the Valar moved to Aman, a continent to the west of Middle-earth, where they established their home, Valinor.

Fëanor's sons seized ships from the Teleri, killing many of them, and betrayed others of the Noldor, leaving them to make a perilous passage on foot across the dangerous ice of the Helcaraxë.

Fëanor's firstborn Maedhros wisely chose to move himself and his brothers to the east, away from the rest of their kin, knowing that they would easily be provoked into war if they lived too close to their kinsmen.

Finrod hewed cave dwellings which became the realm of Nargothrond, while Turgon discovered a hidden vale surrounded by mountains, and chose that to build the city of Gondolin.

Beren, a Man who had survived the latest battle, wandered into Doriath, where he fell in love with the Elf maiden Lúthien, daughter of Thingol and Melian.

Despite his heroism, however, Túrin fell under the curse of Melkor, which led him to unwittingly murder his friend Beleg and marry and impregnate his sister Nienor Níniel, who had lost her memory through Glaurung's enchantment.

In anguish, Maedhros killed himself by leaping into a fiery chasm with his Silmaril, while Maglor threw his jewel into the sea and spent the rest of his days wandering along the shores of the world, singing his grief.

Among these survivors were Elendil, their leader and a descendant of Elros, and his sons Isildur and Anárion, who had saved a seedling from Númenor's white tree, the ancestor of that of Gondor.

Christopher selected the most complete stories and compiled them into a single volume, in line with his father's desire to create a body of work that spanned from the Creation of the World to the destruction of the One Ring.

Due to this circumstance, the volume sometimes exhibits inconsistencies with "The Lord of the Rings" or "The Hobbit," with varying styles and featuring fully developed stories like Beren and Lúthien, or more loosely outlined ones, such as those dedicated to the War of Wrath.

[14] As explained in The History of Middle-earth, Christopher Tolkien drew upon numerous sources, relying on post-Lord of the Rings works where possible, ultimately reaching as far back as the 1917 Book of Lost Tales to fill in portions of the narrative that his father had planned to write but never addressed.

In his foreword to The Book of Lost Tales 1 in 1983, he wrote that[T 22] by its posthumous publication nearly a quarter of a century later the natural order of presentation of the whole 'Matter of Middle-earth' was inverted; and it is certainly debatable whether it was wise to publish in 1977 a version of the primary 'legendarium' standing on its own and claiming, as it were, to be self-explanatory.

[20] As with all of Tolkien's works, The Silmarillion allows room for later Christian history, and one draft even has Finrod speculating on the necessity of Eru's eventual Incarnation to save mankind.

Dimitra Fimi has documented the influence of Celtic mythology in the exile of the Noldorin Elves, borrowing elements from the story of Irish legends of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

[22] Welsh influence is seen in the Elvish language Sindarin; Tolkien wrote that he gave it "a linguistic character very like (though not identical with) British-Welsh ... because it seems to fit the rather 'Celtic' type of legends and stories told of its speakers".

He suggested that the main reason for its "enormous sales" was the "Tolkien cult" created by the popularity of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and predicted that more people would buy The Silmarillion than would ever read it.

[35] John Calvin Batchelor, in The Village Voice, lauded the book as a "difficult but incontestable masterwork of fantasy" and praised the characterisation of Melkor, describing him as "a stunning bad guy" whose "chief weapon against goodness is his ability to corrupt men by offering them trappings for their vanity".

[39] Gergely Nagy writes that The Silmarillion is long both in Middle-earth time and in years of Tolkien's life; and it provides the impression of depth for both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

[3] Nagy notes that in 2009, Douglas Charles Kane published a "hugely important resource", his Arda Reconstructed,[41] which defines "exactly from what sources, variants, and with what methods" Christopher Tolkien constructed the 1977 book.

One key theme is its nature as a mythology, with multiple interrelated texts in differing styles;[42] David Bratman has named these as "Annalistic", "Antique" and "Appendical".

[3] Verlyn Flieger analyses at length Tolkien's way of thinking of his own mythology as a presented collection, with a frame story that changed over the years, first with a seafarer called Eriol or Ælfwine who records the sayings of the "fairies" or translates the "Golden Book" of the sages Rumil or Pengoloð; later, he decided that the Hobbit Bilbo Baggins collected the stories into the Red Book of Westmarch, translating Elvish documents in Rivendell.

[49] Nagy observes that this means that Tolkien "thought of his works as texts within the fictional world" (his emphasis), and that the overlapping of different accounts was central to his desired effect.

His son and literary executor Christopher decided to construct "a single text, selecting and arranging in such a way as seemed to me to produce the most coherent and internally self-consistent narrative.

[T 32] The result is certainly unlike the mass of overlapping documents of the legendarium; it differs, too, in style and rhythm; and Christopher was obliged to invent story elements, both to fill gaps in the narrative, and to connect threads that simply did not fit together as they stood.

[54] The Norwegian classical composer Martin Romberg has written three full-scale symphonic poems, "Quendi" (2008), "Telperion et Laurelin" (2014), and "Fëanor" (2017), inspired by passages from The Silmarillion.