History of Arda

This period, known as the Spring of Arda, was a time when the Valar had ordered the World as they wished and rested upon Almaren, and Melkor lurked beyond the Walls of Night.

The first Elves awoke in Cuiviénen in the middle of Middle-earth, marking the start of the First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar, and were soon approached by the Enemy Melkor who hoped to enslave them.

[T 5] After Melkor appeared to repent and was released after his servitude of three Ages, he stirred up rivalry between the Noldorin King Finwë's two sons Fëanor and Fingolfin.

[T 10] The Years of the Sun began towards the end of the First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar and continued through the Second, Third, and part of the Fourth in Tolkien's stories.

[T 11] The First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar (Eruhíni) began during the Years of the Trees when the Elves awoke in Cuiviénen in the middle-east of Middle-earth.

In the Dagor Aglareb ("Glorious Battle"), the armies of the Noldor led by Fingolfin and Maedhros attacked from the east and west, destroying the invading Orcs and laid siege to Morgoth's stronghold Angband.

[T 16] The Elves, Men, and Dwarves were all disastrously defeated in the Nírnaeth Arnoediad ("Battle of Unnumbered Tears"),[T 17] and one by one, the kingdoms fell, even the hidden ones of Doriath[T 18] and Gondolin.

[T 19] At the end of the age, all that remained of free Elves and Men in Beleriand was a settlement at the mouth of the River Sirion and another on the Isle of Balar.

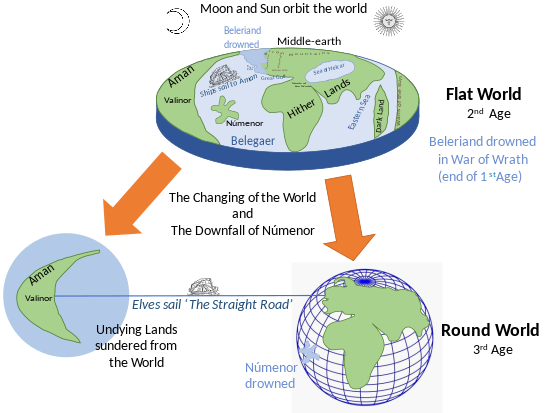

[T 21][e] At the start of the Second Age, the Men who had remained faithful were given the island of Númenor, in the middle of the Great Sea, and there they established a powerful kingdom.

At this time, the Faithful (who still worshipped the one god, Eru Ilúvatar), were persecuted openly by those called the King's Men, and were sacrificed in the name of Melkor.

His son Elendil and grandsons Isildur and Anárion prepared to flee eastwards, taking with them a seedling of the White Tree of Númenor before Sauron destroyed it, and the palantíri, gifts of the elves.

When the King's forces set foot on Aman, the Valar laid down their guardianship of the world and called on Ilúvatar to intervene.

Afterward, Isildur ignored the counsel of Elrond, and rather than destroy the One Ring in the fires of Mount Doom, he kept it as weregild for his dead father.

In Gondor the Plague caused many deaths, including King Telemnar, his children, and the White Tree; the population of the capital city Osgiliath was decimated, and government of the kingdom was transferred to Minas Tirith.

During this period Gondor strengthened its borders, keeping a watchful eye on the east, as Minas Morgul was still a threat on their flank and Mordor was still occupied with Orcs.

A similar fate meets the Dwarves: although Erebor becomes an ally of the Reunited Kingdom, there are indications that Khazad-dûm is refounded together with a colony established by Gimli in the White Mountains.

[6] Verlyn Flieger cites Tolkien's poem Mythopoeia ("Creation of Myth"), where he speaks of "man, sub-creator, the refracted light / through whom is splintered from a single White / to many hues, and endlessly combined / in living shapes".

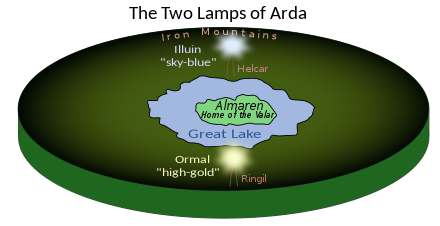

[T 36][7] She analyses in detail the successive splintering of the original created light, via the Two Lamps, the Two Trees, and the Silmarils, as the wills of different beings conflict.

[7] Jane Chance remarks on the biblical theme of the conflict between the creator Eru Ilúvatar and the fallen Vala Melkor/Morgoth, mirroring that between God and Satan.

Similarly, she notes, the struggles of Elves and Men corrupted by Morgoth and his spiritual descendant Sauron echo those of Adam and Eve tempted by Satan in the Garden of Eden, and the fall of man.

[11] Scholars including Flieger have noted that if Tolkien intended to create a mythology for England,[12] in the history of Arda as told in The Silmarillion he had made it very dark.

[14] Flieger suggests that Middle-earth arose not only from Tolkien's own wartime experience, but out of that of his dead schoolfriends Geoffrey Bache Smith and Rob Gilson.

[15] Janet Brennan Croft writes that Tolkien's first prose work after returning from the war was The Fall of Gondolin, and that it is "full of extended and terrifying scenes of battle"; she notes that the streetfighting is described over 16 pages.

[16] The Tolkien scholar Norbert Schürer notes the 2022 book The Fall of Númenor and the Amazon television series The Rings of Power, both about the Second Age, and asks what the period signifies for the legendarium as a whole.

"[1] Kocher notes Tolkien's statement in the Prologue, equating Middle-earth with the actual Earth, separated by a long period of time: Those days, the Third Age of Middle-earth, are now long past, and the shape of all lands has been changed; but the regions in which Hobbits then lived were doubtless the same as those in which they still linger: the North-West of the Old World, east of the Sea.

"[3] West observes that this points up a "highly unusual" aspect of Tolkien's legendarium among modern fantasy: it is set "in the real world but in an imagined prehistory.

"[3] As a result, West explains, Tolkien can build what he likes in that distant past, elves and wizards and hobbits and all the rest, provided that he tears it all down again, so that the modern world can emerge from the wreckage, with nothing but "a word or two, a few vague legends and confused traditions..." to show for it.

[3] West praises and quotes Kocher on Tolkien's imagined prehistory and the implied process of fading to lead from fantasy to the modern world:[3] At the end of his epic Tolkien inserts ... some forebodings of [Middle-earth's] future which will make Earth what it is today ... he shows the initial steps in a long process of retreat or disappearance by which all other intelligent species, which will leave man effectually alone on earth... Ents may still be there in our forests, but what forests have we left?

"[5] The poet W. H. Auden wrote in The New York Times that "no previous writer has, to my knowledge, created an imaginary world and a feigned history in such detail.

By the time the reader has finished the trilogy, including the appendices to this last volume, he knows as much about Tolkien's Middle Earth, its landscape, its fauna and flora, its peoples, their languages, their history, their cultural habits, as, outside his special field, he knows about the actual world.