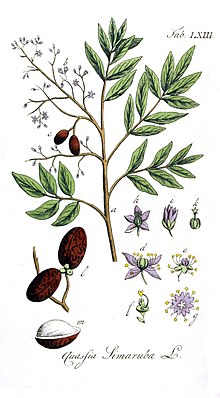

Simarouba amara

Simarouba amara is a species of tree in the family Simaroubaceae, found in the rainforests and savannahs of South and Central America and the Caribbean.

Many of these studies were conducted on Barro Colorado Island in Panama or at La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica.

It is genetically diverse, indicating gene flow occurs between populations and seeds can be dispersed up to 1 km.

Local people use the wood of the tree for various purposes and it is also grown in plantations and harvested for its timber, some of which is exported.

[5] Each seed weighs approximately 0.25 g.[6] It is an evergreen species, with a new flush of leaves growing between January and April, during the dry season, when the highest light levels occur in the rainforest.

[1][2] In 1790, William Wright described Quassia simarouba,[15] which Auguste Pyrame DeCandolle suggested was the same species as S. amara.

S. amara can be distinguished from the other continental species by having smaller flowers, anthers and fruit, and straight, rather than curved petals.

Its range extends from Guatemala in the north, to Bolivia in the south and from Ecuador in the west, to the east coast of Brazil.

[25] A study of 300 plants on Barro Colorado Island found that the heterozygosity at 5 microsatellite loci varied between 0.12 and 0.75.

[32] Based on inverse modelling of data from seed traps on BCI, the estimated average dispersal distance for seeds is 39 m.[5] Studying seedlings and parent trees on BCI using DNA microsatellites revealed that, in fact on average, seedlings grow 392 m away from their parents, with a standard deviation of ±234 m and a range of between 9 m and 1 km.

The stomatal conductance of the leaves, an indication of the rate at which water evaporates, of mature trees at midday range from 200 to 270 mmol H2O m−2 s−1.

They concluded that water flux in S. amara is controlled by structural (leaf area), rather than physiological (closing stomata) means.

Generally plants absorb PAR at efficiencies of around 85%; the higher values found in S. amara are thought to be due to the high humidity of its habitat.

[35] (dry weight) Experiments on BCI where trenches were dug around seedlings of S. amara, or where gaps in the canopy were made above them, show that their relative growth rate can be increased by both.

Competition for light is normally more important, as shown by the growth rate increasing by almost 7 times and mortality decreasing, when seedlings were placed in gaps, compared to the understory.

Trenching around seedlings in the understory did not significantly increase their growth, showing that they are normally only limited by competition for light.

A study on individuals on BCI found that this pattern may be caused by differences in soil biota rather than by insect herbivores or fungal pathogens.

[29] Saplings of S. amara are light demanding and are found in brighter areas of the rainforest compared to Pitheullobium elegans and Lecythis ampla seedlings.

[13] Another study of saplings at La Selva found that they grew 7 cm yr−1 in height and 0.25 mm yr−1 in diameter.

Putz suggested that this may be due to the trees having large leaves, but the mechanism by which this would reduce the number of lianas is unknown.

[40] The larvae of the butterfly species, Bungalotis diophorus feed exclusively on saplings and treelets of S. amara.

[41] Two termite species have been observed living on S. amara in Panama, Calcaritermes brevicollis in dead wood and Microcerotermes arboreus nesting in a gallery on a branch.

[5] It is also grown in plantations, as its bright and lightweight timber is highly sought after in European markets for use in making fine furniture and veneers.

[19] It has been noted to be one of the best species for timber that can be grown in the Peruvian Amazon, along with Cedrelinga catenaeformis, due to its rapid growth characteristics.

[47] The Worldwide Fund for Nature recommend that consumers ensure S. amara timber is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council so that they do not contribute to deforestation.

[49] The leaves and bark of S. amara have been used as an herbal medicine to treat dysentery, diarrhea, malaria and other illnesses in areas where it grows.

In 1918 its effectiveness was validated by a study where soldiers in a military hospital were given a tea made of the bark to treat amoebic dysentery.

[medical citation needed] In a 1944 study, the Merck Institute found it was 92% effective at treating intestinal amoebiasis in humans.

The main biologically active compounds found in S. amara are the quassinoids, a group of triterpenes including ailanthinone, glaucarubinone, and holacanthone.

[medical citation needed] In 1997 a patent was filed in the United States for using an extract in a skin care product.