Sinking of the Titanic

She sank two hours and forty minutes later at 02:20 ship's time (05:18 GMT) on 15 April, resulting in the deaths of more than 1,500 people, making it one of the deadliest peacetime maritime disasters in history.

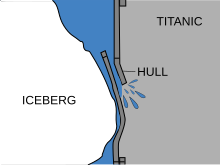

Unable to turn quickly enough, the ship suffered a glancing blow that buckled the steel plates covering her starboard side and opened six of her sixteen compartments to the sea.

Titanic had been designed to stay afloat with up to four of her forward compartments flooded, and the crew used distress flares and radio (wireless) messages to attract help as the passengers were put into lifeboats.

[13] Her passengers were a cross-section of Edwardian society, from millionaires such as John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim,[14] to poor emigrants from countries as disparate as Armenia, Ireland, Italy, Sweden, Syria and Russia seeking a new life in the United States.

[18][19] The weather improved significantly during the day, from brisk winds and moderate seas in the morning to a crystal-clear calm by evening, as the ship's path took her beneath an arctic high-pressure system.

According to Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, the custom was "to go ahead and depend upon the lookouts in the crow's nest and the watch on the bridge to pick up the ice in time to avoid hitting it".

There was a delay before either order went into effect; the steam-powered steering mechanism took up to 30 seconds to turn the ship's tiller,[24] and the complex task of stopping the engines would also have taken some time to accomplish.

[45] At the British inquiry following the accident, Edward Wilding (chief naval architect for Harland & Wolff), calculating on the basis of the observed flooding of forward compartments forty minutes after the collision, testified that the area of the hull opened to the sea was "somewhere about 12 square feet (1.1 m2)".

Modern ultrasound surveys of the wreck have found that the actual damage to the hull was very similar to Wilding's statement, consisting of six narrow openings covering a total area of only about 12 to 13 square feet (1.1 to 1.2 m2).

According to Paul K. Matthias, who made the measurements, the damage consisted of a "series of deformations in the starboard side that start and stop along the hull ... about 10 feet (3 m) above the bottom of the ship".

[52][53] Tom McCluskie, a retired archivist of Harland & Wolff, pointed out that Olympic, Titanic's sister ship, was riveted with the same iron and served without incident for nearly 25 years, surviving several major collisions, including being rammed by a British cruiser.

[64] Several sources later contended that upon grasping the enormity of what was about to happen, Captain Smith became paralysed by indecision, had a mental breakdown or nervous collapse, and was lost in a trance-like daze, being ineffective and inactive in attempting to mitigate the loss of life.

Smith was observed all around the decks, personally overseeing and helping to load the lifeboats, interacting with passengers, and trying to instil urgency to follow evacuation orders while avoiding panic.

The boats were supposed to be stocked with emergency supplies, but Titanic's passengers later found that they had only been partially provisioned despite the efforts of the ship's chief baker, Charles Joughin, and his staff to do so.

[86] Thomas E. Bonsall, a historian of the disaster, has commented that the evacuation was so badly organised that "even if they had the number [of] lifeboats they needed, it is impossible to see how they could have launched them" given the lack of time and poor leadership.

Second Officer Lightoller recalled afterwards that he had to cup both hands over Smith's ears to communicate over the racket of escaping steam, and said, "I yelled at the top of my voice, 'Hadn't we better get the women and children into the boats, sir?'

Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club stepped forward and climbed down a rope into the lifeboat; he was the only adult male passenger whom Lightoller allowed to board during the port side evacuation.

They re-opened watertight doors in order to set up extra portable pumps in the forward compartments in a futile bid to reduce the torrent, and kept the electrical generators running to maintain lights and power throughout the ship.

Steward Frederick Dent Ray narrowly avoided being swept away when a wooden wall between his quarters and the third-class accommodation on E deck collapsed, leaving him waist-deep in water.

4, at around 01:20 according to survivor trimmer George Cavell, water began flooding in from the metal floor plates below, possibly indicating that the bottom of the ship had also been holed by the iceberg.

[48] Several sources contend they remained at their posts until the very end, thus ensuring that Titanic's electrics functioned until the final minutes of the sinking, and died in the bowels of the ship.

However, there is evidence to suggest when it became obvious that nothing more could be done, and the flooding in the forward compartments was too severe for the pumps to cope, some of the engineers and other crewmen abandoned their posts and came up onto Titanic's deck, but by this time all the lifeboats had left.

It was aboard this boat that White Star chairman and managing director J. Bruce Ismay, Titanic's most controversial survivor, made his escape from the ship, an act later condemned as cowardice.

"[174] Titanic was subjected to extreme opposing forces – the flooded bow pulling her down while the air in the stern kept her to the surface – which were concentrated at one of the weakest points in the structure, the area of the engine room hatch.

Thayer reported that it rotated on the surface, "gradually [turning] her deck away from us, as though to hide from our sight the awful spectacle ... Then, with the deadened noise of the bursting of her last few gallant bulkheads, she slid quietly away from us into the sea.

The ship was held together by the B-Deck, which featured 6 large doubler plates – trapezoidal steel segments meant to prevent cracks from forming in the smokestack uptake while at sea – which acted as a buffer and pushed the fractures away.

[187] After they went under, the bow and stern took only about 5–6 minutes to sink 3,795 metres (12,451 ft), spilling a trail of heavy machinery, tons of coal and large quantities of debris from Titanic's interior.

No one in any of the boats standing off a few hundred yards away can have escaped the paralysing shock of knowing that so short a distance away a tragedy, unbelievable in its magnitude, was being enacted, which we, helpless, could in no way avert or diminish.

[211] Titanic's survivors were rescued around 04:00 on 15 April by the RMS Carpathia, which had steamed through the night at high speed and at considerable risk, as the ship had to dodge numerous icebergs en route.

[252] Eventually Titanic's structure will collapse, and she will be reduced to a patch of rust on the seabed, with any remaining scraps of the ship's hull mingled with her more durable fittings, like the propellers, bronze capstans, compasses and the telemotor.

![Image of a distress signal reading: "SOS SOS CQD CQD. MGY [Titanic]. We are sinking fast passengers being put into boats. MGY"](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Titanic_signal.jpg/300px-Titanic_signal.jpg)