Sino-Tibetan languages

Early in the following century, Brian Houghton Hodgson and others noted that many non-literary languages of the highlands of northeast India and Southeast Asia were also related to these.

[9] Studies of the "Indo-Chinese" languages of Southeast Asia from the mid-19th century by Logan and others revealed that they comprised four families: Tibeto-Burman, Tai, Mon–Khmer and Malayo-Polynesian.

Julius Klaproth had noted in 1823 that Burmese, Tibetan, and Chinese all shared common basic vocabulary but that Thai, Mon, and Vietnamese were quite different.

[12][13] Jean Przyluski introduced the French term sino-tibétain as the title of his chapter on the group in Meillet and Cohen's Les langues du monde in 1924.

[26] This irregularity was attacked by Roy Andrew Miller,[27] though Benedict's supporters attribute it to the effects of prefixes that have been lost and are often unrecoverable.

However, the Chinese script is logographic and does not represent sounds systematically; it is therefore difficult to reconstruct the phonology of the language from the written records.

[35] Similarly, Karlgren's *l has been recast as *r, with a different initial interpreted as *l, matching Tibeto-Burman cognates, but also supported by Chinese transcriptions of foreign names.

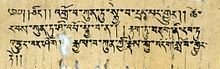

Most comparative work has used the conservative written forms of these languages, following the dictionaries of Jäschke (Tibetan) and Judson (Burmese), though both contain entries from a wide range of periods.

[44][45] Most of the smaller Sino-Tibetan languages are spoken in inaccessible mountainous areas, many of which are politically or militarily sensitive and thus closed to investigators.

The remaining languages are spoken in mountainous areas, along the southern slopes of the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau.

[53] Burmese speakers first entered the northern Irrawaddy basin from what is now western Yunnan in the early ninth century, in conjunction with an invasion by Nanzhao that shattered the Pyu city-states.

[55] The closely related Loloish languages are spoken by 9 million people in the mountains of western Sichuan, Yunnan, and nearby areas in northern Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam.

[63] Sagart et al. (2019) performed another phylogenetic analysis based on different data and methods to arrive at the same conclusions to the homeland and divergence model but proposed an earlier root age of approximately 7,200 years ago, associating its origin with millet farmers of the late Cishan culture and early Yangshao culture.

[75][76] Thus, a conservative classification of Sino-Tibetan/Tibeto-Burman would posit several dozen small coordinate families and isolates; attempts at subgrouping are either geographic conveniences or hypotheses for further research.

In the Western scholarly community, these languages are no longer included in Sino-Tibetan, with the similarities attributed to diffusion across the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, especially since Benedict (1942).

He otherwise retained the outlines of Conrady's Indo-Chinese classification, though putting Karen in an intermediate position:[80][81] Shafer criticized the division of the family into Tibeto-Burman and Sino-Daic branches, which he attributed to the different groups of languages studied by Konow and other scholars in British India on the one hand and by Henri Maspero and other French linguists on the other.

[82] He proposed a detailed classification, with six top-level divisions:[83][84][e] Shafer was sceptical of the inclusion of Daic, but after meeting Maspero in Paris decided to retain it pending a definitive resolution of the question.

[88] Sergei Starostin proposed that both the Kiranti languages and Chinese are divergent from a "core" Tibeto-Burman of at least Bodish, Lolo-Burmese, Tamangic, Jinghpaw, Kukish, and Karen (other families were not analysed) in a hypothesis called Sino-Kiranti.

The proposal takes two forms: that Sinitic and Kiranti are themselves a valid node or that the two are not demonstrably close so that Sino-Tibetan has three primary branches: George van Driem, like Shafer, rejects a primary split between Chinese and the rest, suggesting that Chinese owes its traditional privileged place in Sino-Tibetan to historical, typological, and cultural, rather than linguistic, criteria.

[94] Orlandi (2021) also considers the van Driem's Trans-Himalayan fallen leaves model to be more plausible than the bifurcate classification of Sino-Tibetan being split into Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman.

[95] Roger Blench and Mark W. Post have criticized the applicability of conventional Sino-Tibetan classification schemes to minor languages lacking an extensive written history (unlike Chinese, Tibetic, and Burmese).

They find that the evidence for the subclassification or even ST affiliation in all of several minor languages of northeastern India, in particular, is either poor or absent altogether.

The use of pseudo-genetic labels such as "Himalayish" and "Kamarupan" inevitably gives an impression of coherence which is at best misleading.In their view, many such languages would for now be best considered unclassified, or "internal isolates" within the family.

[103] While Benedict contended that Proto-Tibeto-Burman would have a two-tone system, Matisoff refrained from reconstructing it since tones in individual languages may have developed independently through the process of tonogenesis.

[110] Notably, Gyalrongic and Kiranti have an inverse marker prefixed to a transitive verb when the agent is lower than the patient in a certain person hierarchy.

[112][113] Although not very common in some families and linguistic areas like Standard Average European, fairly complex systems of evidentiality (grammatical marking of information source) are found in many Tibeto-Burman languages.

[134] The "Sino-Caucasian" hypothesis of Sergei Starostin posits that the Yeniseian languages form a clade with Sino-Tibetan, which he called Sino-Yeniseian.

In 1925, a supporting article summarizing his thoughts, albeit not written by him, entitled "The Similarities of Chinese and Indian Languages", was published in Science Supplements.

The Sino-Dene hypothesis never gained foothold in the United States outside of Sapir’s circle, though it was later revitalized by Robert Shafer (1952, 1957, 1969) and Morris Swadesh (1952, 1965).

[141] A 2023 analysis by David Bradley using the standard techniques of comparative linguistics supports a distant genetic link between the Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené, and Yeniseian language families.

|

Sinitic (94.3%)

Lolo–Burmese (3.4%)

Tibetic (0.4%)

|

Karenic (0.3%)

others (1.6%)

|