Charles Wheatstone

When he was about fourteen years old he was apprenticed to his uncle and namesake, a maker and seller of musical instruments at 436 Strand, London; but he showed little taste for handicraft or business, and loved better to study books.

Then he began to read the volume, and, with the help of his elder brother, William, to repeat the experiments described in it, with a home-made battery, in the scullery behind his father's house.

Though silent and reserved in public, Wheatstone was a clear and voluble talker in private, if taken on his favourite studies, and his small but active person, his plain but intelligent countenance, was full of animation.

Sir Henry Taylor tells us that he once observed Wheatstone at an evening party in Oxford earnestly holding forth to Lord Palmerston on the capabilities of his telegraph.

A reminiscence of this interview may have prompted Palmerston to remark that a time was coming when a minister might be asked in Parliament if war had broken out in India, and would reply, 'Wait a minute; I'll just telegraph to the Governor-General, and let you know.'

Water, and solid bodies, such as glass, or metal, or sonorous wood, convey the modulations with high velocity, and he conceived the plan of transmitting sound-signals, music, or speech to long distances by this means.

(Robert Hooke, in his Micrographia, published in 1667, writes: 'I can assure the reader that I have, by the help of a distended wire, propagated the sound to a very considerable distance in an instant, or with as seemingly quick a motion as that of light.'

A writer in the Repository of Arts for 1 September 1821, in referring to the 'Enchanted Lyre,' beholds the prospect of an opera being performed at the King's Theatre, and enjoyed at the Hanover Square Rooms, or even at the Horns Tavern, Kennington.

Charles had no great liking for the commercial part, but his ingenuity found a vent in making improvements on the existing instruments, and in devising philosophical toys.

It enables two lights to be compared by the relative brightness of their reflections in a silvered bead, which describes a narrow ellipse, so as to draw the spots into parallel lines.

He also improved the speaking machine of De Kempelen, and endorsed the opinion of Sir David Brewster, that before the end of this century a singing and talking apparatus would be among the conquests of science.

He cut the wire at the middle, to form a gap which a spark might leap across, and connected its ends to the poles of a Leyden jar filled with electricity.

Decades later, after the telegraph had been commercialised, Michael Faraday described how the velocity of an electric field in a submarine wire, coated with insulator and surrounded with water, is only 144,000 miles per second (232,000 km/s), or still less.

[9][10][11] As John Munro wrote in 1891, "In 1835, at the Dublin meeting of the British Association, Wheatstone showed that when metals were volatilised in the electric spark, their light, examined through a prism, revealed certain rays which were characteristic of them.

A joint patent was taken out for their inventions, including the five-needle telegraph of Wheatstone,[13] and an alarm worked by a relay, in which the current, by dipping a needle into mercury, completed a local circuit, and released the detent of a clockwork.

The five-needle telegraph, which was mainly, if not entirely, due to Wheatstone, was similar to that of Schilling, and based on the principle enunciated by Ampère – that is to say, the current was sent into the line by completing the circuit of the battery with a make and break key, and at the other end it passed through a coil of wire surrounding a magnetic needle free to turn round its centre.

An experimental line, with a sixth return wire, was run between the Euston terminus and Camden Town station of the London and North Western Railway on 25 July 1837.

Cooke was in charge at Camden Town, while Robert Stephenson and other gentlemen looked on; and Wheatstone sat at his instrument in a dingy little room, lit by a tallow candle, near the booking-office at Euston.

Their circuit was eventually extended to Slough in 1841, and was publicly exhibited at Paddington as a marvel of science, which could transmit fifty signals a distance of 280,000 miles per minute (7,500 km/s).

The price of admission was a shilling (£0.05), and in 1844 one fascinated observer recorded the following: It is perfect from the terminus of the Great Western as far as Slough – that is, eighteen miles; the wires being in some places underground in tubes, and in others high up in the air, which last, he says, is by far the best plan.

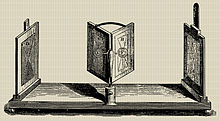

We were taken into a small room (we being Mrs Drummond, Miss Philips, Harry Codrington and myself – and afterwards the Milmans and Mr Rich) where were several wooden cases containing different sorts of telegraphs.

They concluded with the words: 'It is to the united labours of two gentlemen so well qualified for mutual assistance that we must attribute the rapid progress which this important invention has made during five years since they have been associated.'

From 1836 to 1837 Wheatstone had thought a good deal about submarine telegraphs, and in 1840 he gave evidence before the Railway Committee of the House of Commons on the feasibility of the proposed line from Dover to Calais.

In 1870 the electric telegraph lines of the United Kingdom, worked by different companies, were transferred to the Post Office, and placed under Government control.

On the night of 8 April 1886, when Gladstone introduced his Bill for Home Rule in Ireland, no fewer than 1,500,000 words were dispatched from the central station at St. Martin's-le-Grand by 100 Wheatstone transmitters.

The plan of sending messages by a running strip of paper which actuates the key was originally patented by Alexander Bain in 1846; but Wheatstone, aided by Augustus Stroh, an accomplished mechanician, and an able experimenter, was the first to bring the idea into successful operation.

It is based on the fact discovered by Sir David Brewster, that the light of the sky is polarised in a plane at an angle of ninety degrees from the position of the sun.

It follows that by discovering that plane of polarisation, and measuring its azimuth with respect to the north, the position of the sun, although beneath the horizon, could be determined, and the apparent solar time obtained.

The device is of little service in a country where watches are reliable; but it formed part of the equipment of the 1875–1876 North Polar expedition commanded by Captain Nares.

Wheatstone was erroneously believed by many to have created the atmospheric electricity observing apparatus that Ronalds invented and developed at the observatory in the 1840s and also to have installed the first automatic recording meteorological instruments there (see for example, Howarth, p158).