Sir George Stokes, 1st Baronet

Born in County Sligo, Ireland, Stokes spent all of his career at the University of Cambridge, where he was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics from 1849 until his death in 1903.

As a physicist, Stokes made seminal contributions to fluid mechanics, including the Navier–Stokes equations; and to physical optics, with notable works on polarisation and fluorescence.

In 1893 he received the Royal Society's Copley Medal, then the most prestigious scientific prize in the world, "for his researches and discoveries in physical science".

Stokes's extensive correspondence and his work as Secretary of the Royal Society has led him to be referred to as a gatekeeper of Victorian science, with his contributions surpassing his own published papers.

[2] Alongside a lifelong commitment to his Protestant faith, Stokes's childhood in Skreen had a strong influence on his later decision to pursue fluid dynamics as a research area.

Stokes did not hold that position for long, for he died at Cambridge on 1 February the following year,[6] and was buried in the Mill Road cemetery.

[6] Stokes was the oldest of the trio of natural philosophers, James Clerk Maxwell and Lord Kelvin being the other two, who especially contributed to the fame of the Cambridge school of mathematical physics in the middle of the 19th century.

[8] In scope, Stokes's work covered a wide range of physical inquiry but, as Marie Alfred Cornu remarked in his Rede Lecture of 1899,[9] the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

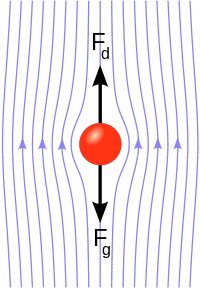

[10] Stokes's work on fluid motion and viscosity led to his calculating the terminal velocity for a sphere falling in a viscous medium.

[citation needed] The same theory explains why small water droplets (or ice crystals) can remain suspended in air (as clouds) until they grow to a critical size and start falling as rain (or snow and hail).

In 1883, during a lecture at the Royal Institution, Lord Kelvin said he had heard an account of it from Stokes many years before, and had repeatedly but vainly begged him to publish it.

[27] In the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and resolution of streams of polarised light from different sources,[28] and in 1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection exhibited by certain non-metallic substances.

William Vernon Harcourt, he investigated the relation between the chemical composition and the optical properties of various glasses, with reference to the conditions of transparency and the improvement of achromatic telescopes.

[38] In other areas of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat in crystals (1851)[39] and his inquiries in connection with Crookes radiometer;[40] his explanation of the light border frequently noticed in photographs just outside the outline of a dark body seen against the sky (1882);[41] and, still later, his theory of the x-rays, which he suggested might be transverse waves travelling as innumerable solitary waves, not in regular trains.

[42] Two long papers published in 1849 – one on attractions and Clairaut's theorem,[43] and the other on the variation of gravity at the surface of the Earth (1849) – Stokes's gravity formula[44]—also demand notice, as do his mathematical memoirs on the critical values of sums of periodic series (1847)[45] and on the numerical calculation of a class of definite integrals and infinite series (1850)[46] and his discussion of a differential equation relating to the breaking of railway bridges (1849),[47][10] research related to his evidence given to the Royal Commission on the Use of Iron in Railway structures after the Dee Bridge disaster of 1847.

In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions, theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time, and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at Glasgow.

[48] These statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it appear that Stokes anticipated Gustav Kirchhoff by at least seven or eight years.

[49] It must be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of spectroscopy.

Then during the thirty years he acted as secretary of the Royal Society, he exercised an enormous if inconspicuous influence on the advancement of mathematical and physical science, not only directly by his own investigations, but indirectly by suggesting problems for inquiry and inciting men to attack them, and by his readiness to give encouragement and help.

In 1886, he became president of the Victoria Institute, which had been founded to defend evangelical Christian principles against challenges from the new sciences, especially the Darwinian theory of biological evolution.

[53] However, although his religious views were mostly orthodox, he was unusual among Victorian evangelicals in rejecting eternal punishment in hell, and instead was a proponent of Christian conditionalism.

They had five children: Arthur Romney, who inherited the baronetcy; Susanna Elizabeth, who died in infancy; Isabella Lucy (Mrs Laurence Humphry) who contributed the personal memoir of her father in "Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of the Late George Gabriel Stokes, Bart"; Dr William George Gabriel, physician, a troubled man who committed suicide aged 30 while temporarily insane; and Dora Susanna, who died in infancy.