Roger Bannister

[3] When asked whether the 4-minute mile was his proudest achievement, he said he felt prouder of his contribution to academic medicine through research into the responses of the nervous system.

Ralph had moved to London at the age of 15 to work in the Civil Service, and met Alice on a trip home.

[7] Here he discovered a talent for cross country running, winning the junior cross-country cup three consecutive times, which led to him being presented with a miniature replica trophy.

Then, in his biggest test to date, he won a mile race on 14 July in 4:07.8 at the AAA Championships at White City before 47,000 people.

[16] From 1951 to 1954, Bannister trained at the track at Paddington Recreation Ground in Maida Vale while he was a medical student at the nearby St Mary's Hospital.

His confidence soon dissipated, however, as it was announced there would be semi-finals for the 1500 m at the Olympics,[12][13] which he felt favoured runners who had much deeper training regimens than he did.

[19] The race was not decided until the final metres, Josy Barthel of Luxembourg prevailing in an Olympic-record 3:45.28 (3:45.1 by official hand-timing) with the next seven runners all under the old record.

[23] With winds of up to twenty-five miles per hour (40 km/h) before the event,[23] Bannister had said twice that he preferred not to run, to conserve his energy and efforts to break the 4-minute barrier; he would try again at another meet.

The race[23] was broadcast live by BBC Radio and commentated by 1924 Olympic 100 metres champion Harold Abrahams, of Chariots of Fire fame.

Bannister had begun his day at a hospital in London, where he sharpened his racing spikes and rubbed graphite on them so they would not pick up too much cinder ash.

[12] Being a dual-meet format, there were seven men entered in the mile: Alan Gordon, George Dole and Nigel Miller from Oxford University; and four British AAA runners: Bannister, his two pacemakers Brasher and Chataway, and Tom Hulatt.

[26] He teased the crowd by delaying his announcement of Bannister's race time for as long as possible:[27] Ladies and gentlemen, here is the result of event nine, the one mile: first, number forty one, R. G. Bannister, Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, Oxford, with a time which is a new meeting and track record, and which—subject to ratification—will be a new English Native, British National, All-Comers, European, British Empire and World Record.

Knowledgeable track fans are still most impressed by the fact that Bannister ran a four-minute mile on very low-mileage training by modern standards.

[22] On 7 August, at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, B.C., Bannister, running for England, competed against Landy for the first time in a race billed as "The Miracle Mile".

A larger-than-life bronze sculpture of the two men at that moment was created by Vancouver sculptor Jack Harman in 1967 from a photograph by Vancouver Sun photographer Charlie Warner and stood for many years at the entrance to Empire Stadium; after the stadium was demolished the sculpture was moved a short distance away to the Hastings and Renfrew entrance of the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) fairgrounds.

In March 1957, he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps at Crookham, where he started his two years of National Service with the rank of lieutenant.

[35] His major contribution to academic medicine was in the field of autonomic failure, an area of neurology concerning illnesses characterised by the loss of certain automatic responses of the nervous system (for example, elevated heart rate when standing up).

If you offered me the chance to make a great breakthrough in the study of the autonomic nerve system, I'd take that over the four minute mile right away.

[39] Moyra Jacobsson-Bannister was the daughter of the Swedish economist Per Jacobsson, who served as managing director of the International Monetary Fund.

He also said that, in terms of athletic achievement, he felt his performances at the 1952 Olympics and the 1954 Commonwealth Games were more significant than running the sub-4-minute mile.

In a UK poll conducted by Channel 4 in 2002, the British public voted Bannister's historic sub-4-minute mile as number 13 in the list of the 100 Greatest Sporting Moments.

This film is a dramatisation, its major departures from the factual record being the creation of a fictional character as Bannister's coach, who was actually Franz Stampfl, an Austrian, and secondly his meeting his wife, Moyra Jacobsson, in the early 1950s when in fact they met in London only a few months before the Miracle Mile itself took place.

In 1996, Pembroke College at the University of Oxford (where Bannister was Master for eight years) named a building in honour of his achievements.

[48] In March 2004, St Mary's Hospital Medical School named a lecture theatre after Bannister; on display is the stopwatch that was used to time the race, stopped at 3:59.

Bannister also purchased the cup (which bears his name) awarded to the winning team in the annual United Hospitals Cross-Country Championship, organised by London Universities and Colleges Athletics.

In 2012, Bannister carried the Olympic flame at the site of his memorable feat, in the Oxford University track stadium now named after him.

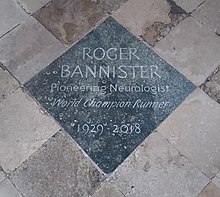

[50] On 28 September 2021, a memorial stone honouring Sir Roger, "pioneering neurologist, world champion runner", was unveiled in Westminster Abbey, in the area known as "Scientists' corner".

[55] In the gallery of Pembroke College dining hall, there is a cabinet containing over 80 exhibits covering Bannister's athletic career and including some academic highlights.

[57] Retired, accomplished milers including Steve Cram, Hicham El Guerrouj, Filbert Bayi, Noureddine Morceli, and Eamonn Coghlan attended, all of whom have had the mile world record to their name.

Finally, on 7 July 1999, El Guerrouj ran 3:43.13, the current mile world record to this day, which is over sixteen seconds faster than Bannister's 3:59.4.