Skylon (spacecraft)

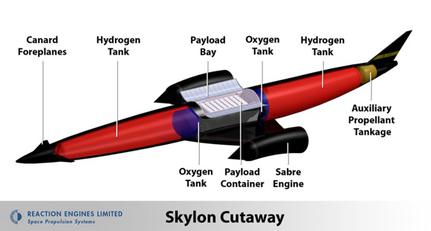

The vehicle design is for a hydrogen-fuelled aircraft that would take off from a specially built reinforced runway, and accelerate to Mach 5.4 at 26 kilometres (85,000 ft) altitude (compared to typical airliner's 9–13 kilometres or 30,000–40,000 feet) using the atmosphere's oxygen before switching the engines to use the internal liquid oxygen (LOX) supply to accelerate to the Mach 25 necessary to reach a 400 km orbit.

The British government pledged £60 million to the project on 16 July 2013 to allow a prototype of the SABRE engine to be built;[13] contracts for this funding were signed in 2015.

[14] In 1982, when work commenced on the HOTOL by several British companies, there was significant international interest to develop and produce viable reusable launch systems, perhaps the most high-profile of these being the NASA-operated Space Shuttle.

Aerospace publication Flight International observed that HOTOL and other competing spaceplane programmes were "over-ambitious" and that development on such launch systems would involve more research and slower progress than previously envisioned.

[16] Following the setback of HOTOL's cancellation, in 1989 Alan Bond, along with John Scott-Scott and Richard Varvill decided to establish their own company, Reaction Engines Limited,[17] to pursue the development of a viable spaceplane and associated technology using private funding.

Skylon was a clean sheet redesign based on lessons learned during development of HOTOL, the new concept again utilised dual-mode propulsion system, using engines that could combust hydrogen with the external air during atmospheric flight.

Early on, Skylon was promoted by the company to the ESA for its Future European Space Transportation Investigations Programme (FESTIP) initiative, as well as seeking out both government or commercial investment in order to finance the vehicle's development.

Reaction has also sought to form ties with other companies with the aim of producing an international consortium of interested firms to participate in the Skylon programme.

Skylon's solution to the issue was to position its engines at the end of its wings, which located them further forward and much closer to the vehicle's longitudinal centre of mass, thereby resolving the instability problem.

[22] According to the company, its business plan is to sell vehicles for $1 billion each, for which it has forecast a market for at least 30 Skylons, while recurring costs of just $10 million per flight are predicted to be incurred by operators.

Speaking in 2009, the former UK Minister for Science and Innovation, Lord Drayson, stated of Reaction: "This is an example of a British company developing world-beating technology with exciting consequences for the future of space.

[30] The 2009 agreement allowed Reaction to involve several external companies, including EADS-owned Astrium, the University of Bristol and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), in further development work.

An expansion deflection nozzle is capable of compensating for the changing ambient pressure encountered while gaining altitude during atmospheric flight, thus generating greater thrust and thereby efficiency.

[52] [needs update] In November 2012, Reaction announced that it would commence work upon a three-and-a-half-year project to develop and build a test rig of the SABRE engine to prove its performance across both the air-breathing and rocket modes.

[54] Proponents of the SSTO approach have often claimed that staging involves a number of inherent complications and problems due to complexity, such as being difficult or typically impossible to recover and reuse most elements, thus unavoidably incurring great expense to produce entirely new launch vehicles instead; therefore, they believe that SSTO designs hold the promise of providing a reduction to the high cost of space flights.

[54] Operationally, it is envisioned for the non-crewed Skylon to take off from a specially strengthened runway, gain altitude in a fashion akin to a conventional aeroplane and perform an ascent at very high speeds, in excess of five times the speed of sound (6,100 km/h or 3,800 mph), to attain a peak air-breathing altitude of roughly 28 kilometres (92,000 ft), where payloads would typically be launched prior to the vehicle's re-entry into the atmosphere, upon which it will conduct a relatively gentle descent before performing a traditional landing upon a runway.

[56] Using interchangeable payload containers, Skylon could be fitted to carry satellites or fluid cargo into orbit, or, in a specialised habitation module, the latter being capable of housing a maximum of 30 astronauts during a single launch.

[61] The weight reduction enabled by the lower quantity of propellant needed meant that the vehicle would not require as much lift or thrust, which in turn permits the use of smaller engines and allows for the use of a conventional wing configuration.

[12] Originally the key technology for this type of precooled jet engine did not exist, as it required a heat exchanger that was ten times lighter than the state of the art.

[61] The SABRE engine design aims to avoid the historic weight-performance issue by using some of the liquid hydrogen fuel to cool helium within a closed-cycle precooler, which quickly reduces the temperature of the air at the inlet.

[65] The fuselage of the Skylon is expected to be a silicon carbide reinforced titanium space frame;[66] a light and strong structure that supports the weight of the aluminium fuel tanks and to which the ceramic skin is attached.

Due to the vehicle's use of a low-density fuel in the form of liquid hydrogen, a great volume is required to contain enough energy to reach orbit.

[69][70] In contrast, the smaller Space Shuttle was heated to 1,730 °C (3,140 °F) on its leading edge, and so employed an extremely heat-resistant but fragile silica thermal protection system.

The Skylon design does not require such an approach, instead opting for using a far thinner yet durable reinforced ceramic skin;[12] however, due to turbulent flow around the wings during re-entry, some sections of the vehicle shall need to be provided with active cooling systems.