Slavery in Latin America

[7] With the ouster of Christopher Columbus, the Spanish crown sent a royal governor, Fray Nicolás de Ovando, who established the formal encomienda system.

Due to the persuasion of Las Casas, Queen Isabella of Castle forbade Indian slavery and deemed the indigenous to be "free vassals of the crown".

[13] The encomienda system brought many indigenous Taíno to work in the fields and mines in exchange for Spanish protection,[14] education, and a seasonal salary[15] under the pretense of searching for gold and other materials.

{{Citation needed}}People like Bartolome de las Casas were the driving forces for having Indian slavery abolished because they were fearful of the drastic decline of the native population.

Today, most African communities live in coastal areas such as Vera Cruz on the Gulf of Mexico and the Costa Chica region on the Pacific".

As a result of this higher percentage, the upper class of these societies constantly feared an uprising among not only slaves but Indians and the poor of all racial and ethnic groups.

[28] Over the next two decades, many other European merchants would pay the Spanish crown for the right to import Africans as slaves to the Americas, further enmeshing unfree labor as a key factor in the colonial Latin American economy.

The majority of slaves brought to the Americas from Africa were men due to the fact plantation owners needed strength for the physical labor that was done in the fields.

During the reign of Charles V, the reformers gained steam, with the Spanish missionary Bartolomé de las Casas as a notable leading advocate.

The second Archbishop of Mexico (1551–72), the Dominican Alonso de Montúfar, wrote to the king in 1560 protesting the importation of Africans, and questioning the "justness" of enslaving them.

Rodrigo de Albornoz, a layman, was a former secretary to Charles V sent as an official to New Spain, who opposed the treatment of the indigenous, though himself importing 150 African slaves.

Las Casas also supported the importation of African slaves as preferable to Amerindian forced labor, although he later changed his mind about this[citation needed].

Within the coffee plantations of the Paraiba Valley, the Brazilian economic center from 1822-1889, the presence of the slave family was very significant in terms of not only population but their purpose.

This was done by allowing slaves the freedom to produce relationships, as well as to freely practice culture and social activities such as singing, praying, dancing, chatting, rest, and community meals.

The planation communities created through family ties and shared hardships, along with other fractional freedoms received from the enslavers, allowed for the coffee plantations within Paraiba to produce high profit and productivity.

[32] The close conditions of these homes made it easy for the enslaved to further connect and develop the community-style relationship that was at the forefront of the fazendas and plantation system of Latin America.

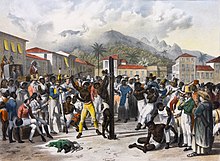

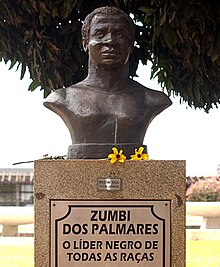

In addition to more passive forms of resistance, such as intentional work slowdowns, the colonial period in Latin America saw the birth of numerous autonomous communities of runaway slaves.

Freedom becomes more popular for those descended people, forcing them to figure out how to take care of their families' needs from an economical standpoint and statues was a primary factor in their drive towards wealth.

It was said that many women used politics in their slave-owning practices but Polonia's additional financial investments helped further her success in her life and other West and Central African-descent slaveowners.

[42] African women whether free or not began to have stipulations on what they were to wear through sumptuary laws enforced by white Limeños, trying to secure that autonomy would not be achieved by their oppressors.

Slaveowners decided that their slaves needed to be dressed in rich clothing to maintain and articulate this elite presence in what is called livery.

[42] For freed African-descent women, they were not supposed to dress like elite Spanish but since they were not the targeted subject, they were able to wear skirts and blouses made of lace.

[45][46] Individuals were then sold into slavery from inside the station and packed into train cars which took them to Veracruz, where they have embarked yet again for the port town of Progreso in the Yucatán.

[45] The Amazon rubber boom and the associated need for an increasing workforce had a significant negative effect on the indigenous population across Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia.

"[49] According to Wade Davis, author of One River: "The horrendous atrocities that were unleashed on the Indian people of the Amazon during the height of the rubber boom were like nothing that had been seen since the first days of the Spanish Conquest.

Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald led violent slave raids against Asháninka, Mashco, Piro, Conibo, Harákmbut and other native groups around the Ucayali, Urubamba, and Manu Rivers between 1880-1897.

[51] Carlos Scharff exploited and enslaved Yine, Machiguenga, Amahuaca, Yaminahua,[52] Mashco, Piro, and other native groups[53] along the Jurua, Purus, and later Las Piedras River until he was killed in 1909 during a mutiny.

[54] Slave raids that were carried out by employees of Nicolás Suárez Callaú led to the destruction of homes, and further persecutions against natives around the Beni and Mamore Rivers.

They would capture women and youths in particular, who formed precious trading objects, whilst adult men were eliminated as they would never form as malleable a workforce as the children, who were more easily and fully assimilated [56][a] In these circumstances, the high death rate and family disintegration caused panic among the mainly native populations, some of whom chose to flee.Many nearby rubber regions were not ruled by physical violence, but by the voluntary compliance implicit in patron-peon relations.

Others chose not to participate in the rubber business and stayed away from the main rivers, because tappers worked in near-complete isolation; they were not burdened by overseers and timetables.